Norman Mailer’s boring Moon landingby Elizabeth Howell

|

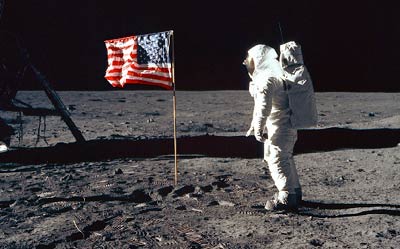

| The feat was a technological one that did not, to Mailer, recognize the philosophical magnitude of men touching the soil of another world. And that robbed the entire event of meaning. |

This frustration with technology rings clear throughout the book, which was supposed to be an exercise in letting go of Mailer’s ego. In the first few pages he explains his recent, failed bid to become mayor of New York. Tired of promoting himself, Mailer rechristens himself “Aquarius” as he narrates—an effort to both embrace the innocent spirit of the Age of Aquarius and to lose himself in the complexities of the space program.

Despite his promise to dismiss his ego, it keeps butting in. The entire first section of the book takes place from the point of view of Aquarius. He compares the look of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston to a bland college campus, or perhaps a prison. He laments how difficult it is to cover the space program when he is forced to watch most of the events on television rather than be there with the explorers.

Most of all, he rails against the technological whiff that the space program gives off. To Mailer, smell is what a subject is about, and it is the lack of smells in space that bothers him. Even the landing crew reeks of this technological nothingness, he claims. He based this assumption from attending a press conference with the entire crew and an individual television interview with Armstrong—while never asking a single question.

Of Buzz Aldrin, Armstrong’s crewmate who followed him on to the Moon, Mailer picks one part of the press conference where Aldrin uses phrases such as “burn condition” and “phasing maneuver” and concludes: “If you did not read technologese, you might as well forget every last remark because his words did not translate.” With Armstrong himself, Mailer complains that his pauses to think are too boring and compares it to static on a plane radio.

What Mailer ignored at the beginning of the book, and only quickly alluded to in the end, was that taking the excitement out of landing on the Moon was necessary to do the job. It was anathema to the author that the crew talked of emergencies as “contingencies” and refused to reflect upon their fate if they could not get off the Moon.

But like today, these men were trained in hours of piloting and engineering to ignore their emotions and to focus on the job at hand. Also like today, the agency was all too close to a disaster where astronauts died: three perished in the Apollo 1 launchpad fire in January 1967. Only two and a half years later, NASA would land on the Moon. It is amazing when one remembers it took two and a half years to launch another space shuttle after the Columbia disaster in 2003.

Furthermore, the agency was fighting for relevance in a country polarized by the Vietnam War, where the young demanded the funds for space research be given away to the disadvantaged. No, going to the Moon had to appear routine. Anything else would give the critics more fodder to cut back funding. There was no other way for the agency to achieve success.

But did the impenetrable phrases, the sit-back attitude of the crew and the bland way of going about business hurt NASA’s bid for the Moon? After all, they succeeded because the mission landed and returned safely. But only three years after Apollo 11, the Apollo program ended. Public ennui is usually cited as the reason why this happened.

| No, going to the Moon had to appear routine. Anything else would give the critics more fodder to cut back funding. There was no other way for the agency to achieve success. |

Perhaps blandness did the program in. But as Mailer alludes to in his book, the astronauts may represent a new type of human being because they understand the beauty behind technology best. Mailer learns enough about his subject to hint at this beauty; he rhymes off long lists of switch functions, or actions as a rocket lifts off, obviously enjoying the powerful images they create. But the astronauts lived in this type of beauty.

As a public we are obsessed with the firsts and the fastest things. Still, there is a rhythm to the blandness of a normal space mission: Watching the astronauts perform a spacewalk they have rehearsed dozens of times before. Hearing the banter between the crew up in space and their support teams down below.

As Shakespeare wrote, there is nothing really good or bad; it is thinking that makes it so. Technology itself is not a good or bad thing, nor a routine space mission. But ignoring space simply because we cannot understand why it is routine is a travesty.

Mailer wrote about his efforts: “To write is to judge.” In the end, as Aquarius he better understood why the space program treated exploration as routine, even though he didn’t agree with it. Before complaining about space being boring, the public would do well to follow in his footsteps.