Galileo and Trident: Britain’s incompatible bedfellowsby Taylor Dinerman

|

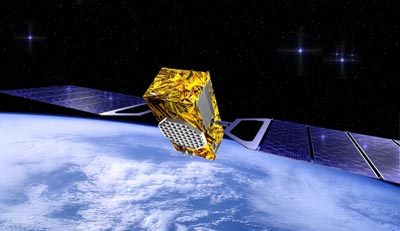

| There is little doubt that Galileo is going to work. It’s not all that hard, and none of the technologies involved is radically new. |

France, and apparently Germany as well, have decided to ignore London’s publicly-stated desire to keep Galileo as a strictly civilian operation and instead are seeking to make it the cornerstone of a future EU military space force. This should not surprise anyone: the Franco-German grand strategic vision for Europe has always included a major “independent” European military force separate from, and opposed to, NATO and the US. President Nicolas Sarkozy of France and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany may not be as personally hostile to America as were their predecessors, but they have shown no sign of backing away from this long-term goal.

The agreement to directly fund Galileo by the EU is described by Europe’s Transportation Commissioner Jacques Barrot as “an indication of our power among the nations of the world.” An interesting formula, which would seem to undermine the idea that the EU is an association of independent nations and is instead the “empire” which European Commission president José Manuel Barroso said it was. In any case the commercial case for the system, which was supposed to be its primary justification, is now definitively dead and buried.

Europe’s emerging military system is so far just a set of bilateral and multilateral arrangements such as the one between France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, and others to use France’s Helios optical satellite imagery. These ad hoc set-ups are obviously temporary in nature and will only last until the EU’s central military command structure is fully up and running. This last, by the way, is going to be one of the priorities of France’s six-month period as EU president next year.

Britain’s role in the EU’s military structure is of critical importance. London controls what may be the most powerful overall set of armed forces in Europe. France may surpass them in certain areas, but across almost the entire broad spectrum of warfare the UK’s power is, in quality if not in quantity, second only to that of the US. This situation may not last. The UK has not only underfunded their forces for the last quarter century at least, but they have made a series of procurement decisions that make the Pentagon’s follies look like the acts of wise and nearly infallible statesmen.

When Sir Glen Torpy spoke about air power at the Air Force Association meeting in Washington DC in September of this year, his only mention of space was a sneering reference to rocket science. The UK’s access to American space assets has allowed them to concentrate their efforts in other areas. They have been able to leverage off the massive and sustained US military space effort for decades. This advantageous position may soon come to an end.

If Europe goes ahead with Galileo and its own military space force, then the need for NATO and for the special relationship will end. After all, Europe is perfectly capable of creating its own air, land, and sea forces, and there is no reason to think they cannot, with enough time and money, create their own space forces as well. If the US brings no added value to Europe’s security architecture, then why bother?

It is only in the area of nuclear weapons that the US role in Europe’s security will be truly unique. Yet that, too, is undermined by the Galileo decision. Military space forces are, by their nature, closely integrated with nuclear forces. This was blindingly true in the early years of the space age, when the first satellite navigation systems were deployed to help guide missile launching submarines. It still is true today, but this fact has been obscured by numerous non-nuclear uses for military space systems.

When one takes this into account, then the establishment of a European military space force will invariably lead to the establishment of a European nuclear weapons force. Last year, after the successful test of their first new generation M-51 submarine-launched missile, France offered to give their future nuclear force a “European dimension”. The details of this were left vague and the idea was generally ignored by most of the press, yet it does represent the logical end state of current process.

| At some point in the next ten years or so Washington will have to ask Britain if they want to do without their connections to the US space and nuclear forces. |

For Britain, this poses a problem that the current government would probably prefer to ignore. In spite of the Labour Party’s traditional hostility to nuclear weapons, they have committed themselves to acquiring a future replacement for their current force of submarine-launched US-built Trident missiles with something similar, some time in the next decade or so. This saves them the huge expense of developing their own missile system, for they merely have to build the submarines and warheads using expertise that they have built up and maintained with some help from the US.

However, if Britain’s nuclear deterrent were to become part of a European nuclear force, then the whole basis on which the US sold them the Tridents would cease to exist. The question is a long-term one, but large-scale projects can only be developed and built over many years. The decisions the British government makes today will have repercussions ten or twenty years from now. The contradictory choices they make now will have to be resolved one way or another.

In keeping with their traditional hostility towards human spaceflight, The Economist magazine greeted China’s first launch of a taikonaut with the headline “So you won’t need any more aid then?” At some point in the next ten years or so Washington will have to ask Britain if they want to do without their connections to the US space and nuclear forces. As they tie their military destiny to that of their continental neighbors, they cannot expect to maintain their links to the US.