Is the shuttle delay good news for the AMS?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| With this latest delay, there is no realistic chance that the Shuttle will be able to fly the rest of the ISS assembly and supply missions, as well as the Hubble repair flight, and also keep to its planned retirement date in September of 2010. |

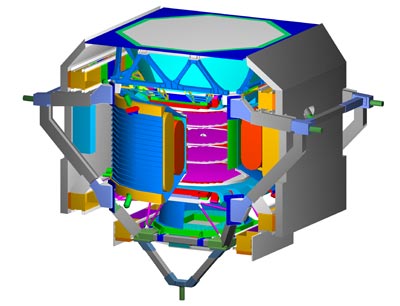

A wild card in all this is the pressure from Capitol Hill, academia, and a number of foreign governments and institutions on NASA to fly at least one extra mission to install the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02) on the ISS. This instrument is designed to search for the existence of antimatter nuclei among primary cosmic rays. AMS-02 is now being built at a cost of more than $1 billion by the US Energy Department and a partnership that includes 16 nations and dozens of universities and scientific institutions.

In 1994, NASA leaders committed to fly the AMS experiments, but after the Columbia disaster of February 2003 they had to take a hard look at the program and decided to limit shuttle flights to the absolute minimum needed to finish the ISS. Congressional and public pressure forced the agency to add on a final servicing flight to the Hubble Space Telescope. In the face of a similar campaign for the AMS-02 will they be able to resist changing the program?

The 2008 omnibus spending bill that Congress passed in December contained the full $17.3 billion that the Administration requested for NASA, but nothing more. The part concerning NASA contained an exceptionally large number of requirements and demands including one that ordered a study of ways to deliver the AMS-02 instrument to the ISS. NASA has been handed a lemon, so they might as well seek to make lemonade.

Any study of a new mission would likely conclude that a decision on whether to launch it must be taken soon, probably sometime between July and September. As the contracting and manufacturing process for the elements of the final missions are completed, the costs for this mission will grow at a geometric rate. Restarting the production line for the main tank and for the four-segment solid rocket boosters, after they have already been shut down or even after the shutdown process has begun, will entail costs that will give pause even to the most pork-barrel-addicted politician.

If NASA is to fly this mission, it will have to ask for a supplemental appropriation and it will have to do so sometime soon. In doing so, they will be fulfilling the legal obligation that Congress laid on them when it demanded this AMS-02 mission feasibility study. Such a request will open the way for those in Congress, like Senator Barbara Mikulski, who have long complained of NASA’s underfunding to insert the $1 billion post-Columbia compensation money that they have long sought to do. It might also be a chance for others, within limits, to provide give some small sums for high priority infrastructure, science, and exploration programs. A total of $1.5 or 2 billion would seem reasonable under the circumstances. It might even be considered a contribution to the government’s economic stimulus program.

Without such a bill the chances of the AMS-02 reaching orbit are slim. In his January 8th speech to the American Astronomical Society, Administrator Mike Griffin was blunt: “No other mission for the Space Shuttle [than the final Hubble servicing mission] has been deemed sufficiently important to justify a further addition to the manifest. Not the dozen ISS utilization flights we had planned to accomplish during the Station’s construction phase, and not the AMS.”

Griffin pointed out that many scientists who are now pushing NASA to take the budgetary and above all the human risks to fly the AMS-02 mission are often contemptuous of human spaceflight and generally hostile to the whole space program. “Speaking forthrightly, I think I can say that, broadly, the scientific community does not support the Nation’s commitment to the Station. But it remains a fact, sustained across four Administrations and over twenty Congressional votes. Like it or not, the Space Station is a feature of American space policy. At this point, the failure to recognize that, accept it, and deal with the consequences in a mature fashion consigns one, in my mind to the ‘kids table’, while the adults converse elsewhere.” Strong words, but having the guts to say them is what makes Griffin who he is.

The hostility of the particle physics community towards the space program is, in some ways, understandable. In 1993 Congress, cheered on by the New York Times, voted to cancel the Superconducting Supercollider and almost canceled the station as well. In doing so, they cut the guts out of America’s preeminent position in this discipline and destroyed the careers of any number of graduate students and young researchers. Since then, the progress of the space station must gall some of them.

| If NASA is to fly this mission, it will have to ask for a supplemental appropriation and it will have to do so sometime soon. |

In historical context, the AMS can be seen as part of the effort to save something from the ruins of the Supercollider catastrophe. In 1994 Professor Samuel CC Ting of MIT, who won a Nobel Prize in 1976, began the effort that would lead to the AMS project. Ting’s long-standing relationships with the European Organization for Nuclear Research (better known by its French acronym, CERN) and with research organizations in China and Taiwan helped him to convince the US Department of Energy to support the AMS program. NASA flew a prototype instrument on the Discovery’s STS-91 mission in June of 1998. He is now lobbying hard to fly the nearly-completed instrument and the agency is feeling the heat.

Griffin said that if Congress wants to fly the AMS on an alternative launch vehicle the price tag is going to be about $400 million. An additional shuttle flight would be cheaper, but would also put yet another crew at risk. The decision to do so cannot be taken lightly. International partners will have to be continually consulted and, if a decision is made to go ahead, they will have to accept part of the responsibility for the additional flight.

Physicists strongly believe that the AMS-02 instrument is going to help them better understand the nature of both antimatter and dark matter. It is doubtful that there is anyone at NASA or in Congress who could dispute them. The decision comes down to a question of budgets and human risks. Sitting in an ivory tower at MIT or at the University of Texas, imperiously aiming thunderbolts of indignation at an agency that is reluctant to risk the lives of its own people and to throw its long-range plans into chaos, is all too easy. One has to wonder if these Nobel Prize winners are more interested in indulging in the dubious joys of NASA bashing than they are in actually getting their experiment to work?