Monster chopperby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Back in 1965 the company made a proposal so bold that it bordered on insane: a giant helicopter with a rotor diameter bigger than the length of a football field, capable not merely of transporting a Saturn 5 first stage, but of actually catching it in midair as it fell on a parachute. |

One of these companies was Hiller Aircraft, a helicopter company based in Palo Alto, California, that thrived in the middle of last century, but was denied a US Army helicopter contract as a result of shady—probably illegal—actions taken by Howard Hughes. Hughes’ OH-6A Cayuse—better known as the Loach—became the Army’s standard light scout helicopter of the Vietnam War, and although Hughes lost substantial money on the Army deal, the Loaches’ descendents proved highly successful. Hiller’s proposal, the OH-5A, lost the Army contract and never succeeded as a commercial helicopter. Hiller was absorbed into Fairchild and eventually the company faded away. Today very few of its products remain flying, and its primary legacy is a small but history-packed museum off Route 101 in Palo Alto.

But back in 1965 the company made a proposal so bold that it bordered on insane: a giant helicopter with a rotor diameter bigger than the length of a football field, capable not merely of transporting a Saturn 5 first stage, but of actually catching it in midair as it fell on a parachute. Strike that—it did not border on insane, it was insane. But those were heady days in the mid-1960s, a time when NASA was getting nearly five percent of the federal budget—ten times more than today—and when the agency was doling out study contracts for everything from nuclear rockets to ion engines to 100-man space stations. The United States was kicking the Soviets’ asses in space. There was nothing we couldn’t do. So why should a small helicopter company that had never gained a major contract, or built a helicopter capable of carrying more than six people, think small?

Of course, they never built it. They never even got money to study it. Their proposal, even if it had not been totally off-the-wall bonkers, came at exactly the time that NASA’s budget was cresting its peak and about to head down, both because the agency had made its initial capital investments like the launch pad facility at Cape Canaveral, and because Lyndon Johnson needed the money for other things and his budget chief recognized (correctly) that there was a lot of fat in the NASA budget. All that is left of Hiller’s proposal is a formerly working model in the company’s museum and the original unsolicited proposal submitted to NASA.

But man, what big imaginations that little helicopter company had.

Hiller did not call their idea a “helicopter,” at least not on the title page. Instead they referred to it as a “Rotary Wing System for Booster Recovery.” In their proposal, Hiller noted that there were many concepts for Saturn first stage recovery, but that these all had drawbacks, including complexity, performance penalties, landing shock damage and/or seawater contamination. Hiller’s helicopter “would recover the booster in its own element”—i.e. in air. The helicopter could also be used as a crane or aerial transport for booster segments.

Closeup of the model of the giant helicopter proposed by Hiller Aircraft. (credit: D. Day) |

It would be a monster. The rotor diameter would be over 120 meters (400 feet). Empty weight would be over 200,000 kilograms (450,000 pounds), with a useful load of nearly 250,000 kilograms (550,000 pounds)—for a gross weight of a whopping 453,000 kilograms (1,000,000 pounds).

According to the proposal, the helicopter would depart from the missile launching area or another suitable base with internal and external fuel tanks (imagine the drop tanks it could carry!) and depart for the booster reentry area. The plan was for the helicopter to be capable of loitering in the recovery area for up to six hours, flying at an altitude of 4,500–6,000 meters (15,000–20,000 feet).

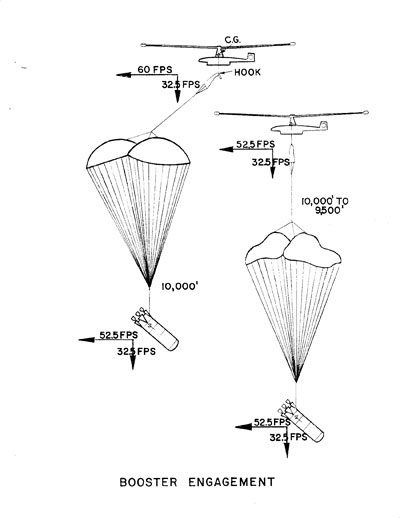

Upon sighting the booster, the helicopter would head for it and intercept it at approximately 3,000 meters (10,000 feet). The S-1C’s parachute system would be descending along a glide path with more forward than downward velocity. The helicopter would align with the glide path and approach from behind and above, descending to match trajectories with the booster. It would snag the pickup chute with a grappling hook suspended from the helicopter’s center of gravity and gradually assume the weight of the booster. The parachutes would be deflated and the booster suspended about 215 meters (700 feet) below the helicopter.

| We don’t know how NASA responded to this idea. They certainly didn’t fund it. |

The helicopter would then reel-in the booster, rotating it to a horizontal position and snugging it up underneath the helicopter—and then returning it to the launch area or some other destination on land. Of course, the S-1C stage would fall over 650 kilometers (350 nautical miles) from the launch site. How feasible was it for the world’s largest helicopter, carrying the world’s largest rocket, to fly this distance back home? What about wind? Although Hiller’s proposal did not say so, a far better solution would have been for the helicopter to set the stage down on a ship near the recovery area. Of course, it would have to be a big ship, like an aircraft carrier, or a barge. But nothing would be small with this concept.

An illustration of how the helicopter would recover the booster stages in midair. (credit: D. Day) |

Oh, and did we mention that this would not be any old helicopter? No, it would utilize a concept that Hiller had worked on for years and tried unsuccessfully to sell to the Army: the rotor-tip-powered lifting system. This involved putting a jet engine, or more likely two jet engines, on the tip of each of the three rotors—six jet engines in all, plus a seventh in the rear fuselage to power the tail rotor. The rotors would not have to turn very fast by helicopter standards, only about once per second. But even that would result in the advancing rotor tip approaching the speed of sound. Not only would it be big, it would be noisy. A mighty roar from a mighty monster chopper.

We don’t know how NASA responded to this idea. They certainly didn’t fund it. They possibly laughed themselves silly and then went back to work, producing their own space geek porn that never got built.

Those were the days. People knew how to dream big.