Canada’s space program in crisisby Chris Gainor

|

| If the sale is approved by shareholders and Canadian and American regulators, the core of Canada’s space business will be under the control of an American corporation. |

On January 8, MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates Ltd. (MDA) of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada’s largest space contractor, announced that it was selling all of its space operations to Alliant Techsystems Inc. (ATK) of Edina, Minnesota, for $1.3 billion. MDA is the corporate home of the shuttle remote manipulator system, known as the Canadarm, the ISS Mobile Servicing System, including Canadarm2, and much of Canada’s communications satellite contracting work. More controversially, MDA operates the recently launched RADARSAT-2 under a joint agreement with the Canadian government.

The following day, the Canadian government announced that the president of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Laurier Boisvert, had resigned a few days earlier after just nine months on the job. Although the resignation was said to be due to personal reasons, speculation has suggested that it was related to the MDA sale.

If the sale is approved by shareholders and Canadian and American regulators, the core of Canada’s space business, supported by massive investments by the Canadian government going back to the early 1960s, will be under the control of an American corporation. While other Canadian space contractors continue to operate, notably Com Dev International of Cambridge, Ontario, the MDA sale encompasses the core of Canada’s space expertise.

Although Canada’s business-friendly Conservative federal government has remained quiet about the sale, leading members of Canada’s largest opposition party, the Liberal Party, have questioned the sale. Among them is Marc Garneau, Canada’s first astronaut and a former CSA president who is now a Liberal candidate in the next federal election, which could take place as early as this spring. The sale is also drawing fire from Canadian trade unionists and from peace activists, who are concerned about ATK’s role as a manufacturer of land mines and other arms.

MDA, which is planning to concentrate on another line of business related to property registry, justified the sale of its space business in part by saying that MDA’s potential for growth in the space sector was constrained by American security restrictions.

“The Canadian market was too small,” MDA founder John MacDonald told the media after the sale, and the company needed to have access to larger markets, especially the one next door.

“We both know that when it comes to advanced technology, free trade is a myth,” MacDonald said, a statement that will be noted by Canadian opponents of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Garneau, who called last fall for a review of Canada’s space policy, said the sale to ATK raises delicate questions of control over the newly launched RADARSAT-2, which will not only sell imaging data on the commercial market but will be used by Canada’s military to monitor Canada’s shoreline, particularly in the arctic.

Canada’s arctic sovereignty is one of the few areas of fundamental difference between the Canadian and US governments. The US government has always insisted that American military and commercial shipping enjoys the right to move through the Northwest Passage between islands in the Canadian arctic.

Climate change is making the question of the Northwest Passage more than academic, and the current Conservative government in Ottawa has publicly differed with the Bush Administration over the issue.

“The concern is we might not have 100 percent control of that satellite from now on,” Garneau said.

| History shows that American control of Canadian space assets is not without precedent, but such a large and unambiguous sale of Canadian space assets will cause Canadian policymakers to look skeptically at further investment in space. |

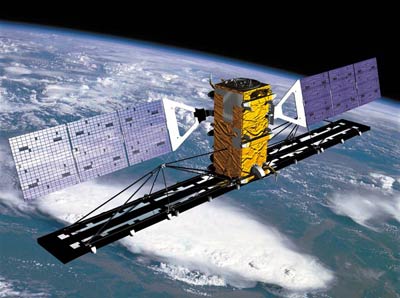

The Canadian government has invested $430 million in RADARSAT-2, and pressed on with the satellite after NASA withdrew from a cooperative arrangement where the American agency launched RADARSAT-1 in 1995 in exchange for data gathered by the satellite’s synthetic aperture radar arrays. RADARSAT-2 was launched on a Soyuz rocket from Baikonur on December 14.

Another point raised by the MDA sale is Canada’s public investment in space technology. Canada’s space program got its start nearly 50 years ago when the Canadian government signed an agreement with the newly established NASA to explore the upper reaches of the Earth’s ionosphere. The result was Canada’s first satellite, Alouette 1, which was launched by NASA in 1962.

While the first Alouette was built largely by government scientists, the second Alouette and subsequent Canadian satellites have been built by private industry, a policy encouraged by Dr. John H. Chapman, the founding figure of Canada’s space program.

When the Canadian government decided to build domestic communications satellites in the late 1960s, it reluctantly agreed to contract their fabrication to Hughes Aircraft in the US on condition that Canadian firms win subcontracting work.

In the wake of this decision, the Canadian government spent large sums of money in the 1970s to strengthen Canada’s communications satellite business. This effort included building a satellite testing laboratory near Ottawa and supporting the Hermes communications technology satellite, which pioneered several technologies, including direct-to-home broadcasting, after its launch in 1976.

While the Canadian branch of the American communications giant RCA was the first Canadian center of communications satellite expertise in the 1960s, this operation was sold to a Canadian firm, Spar Aerospace, and the Canadian government supported Spar’s effort in the 1970s to dominate the Canadian space industry.

When Canada decided to join the US space shuttle program in 1974 by building the shuttle remote manipulator system, Spar won the contract. And in 1982, the first Canadian communications satellite with Spar as the prime contractor was launched.

And although Spar saw success with its shuttle arm and managed to win prime contract work on two Brazilian communications satellites in addition to Canadian comsats, Spar faced problems in the cyclical and competitive satellite business and decided to get out of space contracting in 1998.

| Canada’s impending loss of its space assets also calls into question the role of smaller countries like Canada in the space sector due to the growing importance of military space and continuing consolidation in the aerospace business. |

MDA, by then Spar’s major rival in Canada, snapped up Spar’s robotics business. At the time, MDA’s controlling shareholder was Orbital Sciences Corporation of Dulles, Virginia. The headlines that the Canadarm had been sold to Americans provoked no action from the Canadian government, but Orbital divested itself of MDA in 2001, restoring MDA to Canadian control. In 2005, MDA acquired the former Spar communications satellite operation in Montreal from an American corporation that had owned it for nearly seven years.

This history shows that American control of Canadian space assets is not without precedent, but such a large and unambiguous sale of Canadian space assets will cause Canadian policymakers to look skeptically at further investment in space.

ATK has promised to continue operations in Canada, but the pressure from American authorities that shut MDA out of American military work may also lead to stipulations that such work be done by American workers on American territory.

The MDA sale comes at a time when the final component of the ISS Mobile Servicing System, the Dextre “Canada hand” manipulator, nears launch, and the shuttle program prepares to phase out without a clear picture of any Canadian involvement in the Constellation Program.

Moreover, Canada’s impending loss of its space assets also calls into question the role of smaller countries like Canada in the space sector due to the growing importance of military space and continuing consolidation in the aerospace business.

If the MDA sale and the end of the shuttle program mark the effective end of Canada’s space program, much of the blame must go to the Liberal government that left office two years ago, which ignored calls by Garneau, then CSA’s president, for innovative policies that would have increased Canada’s role in Mars exploration, and the current Conservative government that continued the previous government’s neglect of space policy. The Canadian government needs to act soon to save Canada’s space program.