Space policy optimists and othersby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Compared to the nation’s other problems, space is not seen as being that important. |

It never seems to work out that way. Only rare, transformative presidents like Lyndon B. Johnson and Ronald Reagan have the imagination and the will to make space policy a central part of their administrations. What usually happens is that, once elected, they lack the time and the focus needed to do anything other than allow Congress and the bureaucracy to drive space policy based mostly on the needs to balance long-standing institutional ambitions with budgetary resources.

In the case of the present incumbent, he lacked any deep interest in either military or civil space activities and thus allowed the Pentagon’s bureaucracy to defeat Rumsfeld’s hopes to thoroughly reform the military space program, and only after the Columbia disaster did he come up with a vision for NASA. There is every reason to think that all of the current major candidates are going to be closer to the Bush model than to Johnson or Reagan. Compared to the nation’s other problems, space is not seen as being that important.

This may be shortsighted; after all, space may hold the answer to many of the nation’s problems. For example, students who are drawn into the study of space activities are often inspired to go on to get degrees in the so-called “hard sciences”. No matter what the disputes about the nature of climate change, it would hardly be possible to have an informed discussion without calling on satellite data or on information from NASA’s earth science and heliophysics programs. Without human spaceflight it would hardly be possible to imagine much of a future for a species confined to a single planet.

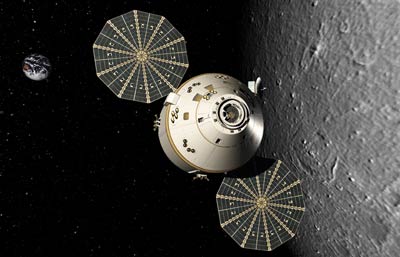

At last week’s National Space Forum, organized in Washington by the Eisenhower Center for Space and Defense Studies and the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a wide range of space experts examined some of the space policy dilemmas that the next administration will face. Space historian Roger Launius raised what may be the biggest question of all, colonization. Are we going to build a base on the Moon because we want to explore it? Because we want to use it for science or to develop technologies for future Mars missions? None of these justifications can really hold up unless the underlying colonization question is answered. Is the lunar outpost that NASA is planning to build sometime around 2025 a glorified campsite, or is it the first step towards a full-scale human settlement on the Moon?

| NASA’s human spaceflight effort survived because it represents something very profound about America, but at some point NASA might find that it has gone to the well once too often. |

A decision in the affirmative would answer the question the Bush’s science advisor John Marburger asked in his March 2006 speech at the Goddard Symposium: “[W]hether we want to incorporate the Solar System in our economic sphere, or not.” In spite of many legitimate questions about the capacity of foreseeable in situ resource utilization (ISRU) technologies to support a fully autonomous settlement, the decision to build a Moon colony would help embed the current strategy into this nation’s long-term plans. To radically change the broad scope of the Vision for Space Exploration (which we are now supposed to call the United States Space Exploration Policy) would probably be the beginning of the end of the US human spaceflight program.

Over the years, the US human space exploration program has gone though a number of near-death experiences, most notably in the aftermath of the Apollo landings and after both the Challenger and Columbia disasters. It survived because it represents something very profound about America, but at some point NASA might find that it has gone to the well once too often. A drastic change in exploration strategy might be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Senior space policy expert John Logsdon said that for the next President, the critical moment will come in the fall of 2009 when he, or she has to make decision concerning the 2011 budget. That will be the moment when the US will truly decide if it wants to lead the way in space for the next twenty or thirty years, or not. If the President decides to retire the shuttle and go ahead with the full Constellation program, then the path will be clear; if not, then not only will China probably beat us back to the Moon, as Mike Griffin and Pete Worden have warned, but the US will lose years or maybe decades while it struggles to find a new vision to replace the one that was thrown away.