BASIC disappointment?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| This is the critical problem for all commercial remote sensing companies, US or foreign: none of them could survive without various kinds of government support. |

This has disappointed America’s two commercial remote sensing companies, GeoEye of Dulles, Virginia, and DigitalGlobe of Longmont, Colorado. This is also a blow to everyone who had hoped that the new commercial remote sensing industry would become a flourishing example of private enterprise in space. There was never any real possibility that, by the end of this decade, dozens of privately-owned spy satellites would be orbiting the Earth selling their pictures commercially while exposing human rights violations and helping to send polluters and other environmental criminals to jail.

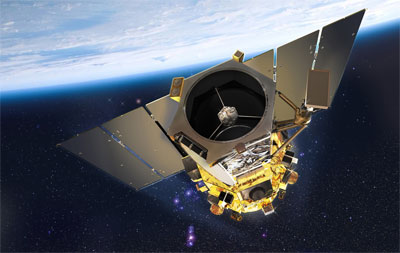

Instead, we have a modest number of highly sophisticated spacecraft and a slightly larger number of relatively simple ones, mostly devoted to governmental purposes, above all military. GeoEye, with its three satellites in orbit, is typical: it has become a small-to-medium-sized specialist firm whose main customer is the US Government’s National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). This month it launched GeoEye-1, whose roughly half-billion-dollar cost was more than half paid for by the NGA. The firm is in healthy financial shape, with 2007 revenues of a little over $180 million. That, of course, would change in an instant if they lost their support from the government.

This is the critical problem for all these companies, US or foreign: none of them could survive without various kinds of government support. The market for private satellite imagery is much too small to sustain the number of firms in the business today. This is simply due to the fact that these types of spacecraft are essentially military assets. They may have a few civilian applications—GeoEye’s list of markets includes state and local governments, forestry, oil and gas, agriculture, real estate, insurance, utilities, and transportation—but they are essentially as military as a bomber or and an aircraft carrier.

The US Commercial Remote Sensing Policy announced by the Bush Administration in April 2003 made this clear. “The fundamental goal of this policy is to advance and protect US national security and foreign policy interests by maintaining the nation’s leadership in remote sensing activities, and by sustaining and enhancing the US remote sensing industry.” This makes it pretty clear that the objective is not to make life easy for the operators of remote sensing satellites, but to keep the industry as a whole in a healthy and robust shape. This means helping manufacturers as well as operators.

The decision by the military and the intelligence community to buy a pair of these satellites is not just healthy for the industry, it’s above all a step towards building a comprehensive space-based intelligence gathering system for the next decade or more. The more eyes in the sky the US has on orbit the better. At some point America’s enemies may find that they cannot freely move anywhere on the surface of the Earth without risking rapid and effective detection. They will still be able to hide indoors or underground or underwater, but the loss of their ability of take a walk in the sun or to drive safely from one place to another will put quite a damper on their movements.

| The decision by the military and the intelligence community to buy a pair of these satellites is not just healthy for the industry, it’s above all a step towards building a comprehensive space-based intelligence gathering system for the next decade or more. |

The meeting between Secretary of Defense Bob Gates and the Director of National Intelligence Michael Mc Connell resembled the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold meeting in 1520 between Henry the Eighth of England and Francis the First of France, a pair of near absolute monarchs, both equally magnificent and powerful and both determined to maintain their prerogatives, prestige, and power. In the end, in spite of all the institutional obstacles, they were able to agree to go forward with this program.

It would be nice if this spirit of cooperation can be maintained when the time comes to buy a set of “cheap and cheerful” radar imaging satellites. The highly capable Space Radar satellites equipped with Ground Moving Target Indicators (GMTI) are just too expensive given current technology. A set of less sophisticated, network enhanced radar satellites using foreign technology could be a quick way to get a fraction of the GMTI requirement into service in a relatively short time.