Chasing the Zondby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Although her crew affectionately called her “the Mighty Mac,” the McMorris was a tiny ship lacking any appreciable armament, or any particular grace… the McMorris looked somewhat awkward, like a chunky adolescent, or worse, a tugboat. |

One thing that landlubbers don’t realize is that ships get to sea and things break. If an engine goes down, sailors refer to it as a “casualty,” and sometimes it means that a ship floats in the ocean until a tug shows up to tow her ignominiously to port. A single screw meant that McMorris or her sisters were vulnerable to engineering casualties and being stuck at sea. But, defying fate, in actual service, the ships’ machinery tended to be reliable. Their crews might have been more effective sailing up to Soviet submarines and throwing rocks, but the ships could travel far on a single tank of gas and they didn’t break down, which made them excellent choices for operating solo. So by the late 1960s the Navy converted McMorris and her sisters for gathering electronic intelligence and fitted them with special antennas.

The Soviet Morzhovets and Nevel were sister ships, both covered with tracking antennas. They were former timber freighters and surprisingly, before they were fitted with the antennas, they were graceful, practically elegant. But they were workers in the space race and they had a job to do. According to Russian space historian Asif Siddiqi, the two ships had entered service as space trackers only a year before the McMorris began dogging them. As Hareland tells it, the Morzhovets and Nevel spent a lot of time out at sea, simply drifting. McMorris did the same, floating a few miles away on relatively calm seas, waiting for whatever the two Soviet tracking ships were waiting for. They called it operating DIW, or drift-in-water.

The Nevel, one of two Soviet vessels that recovered the Zond 5 capsule in the Indian Ocean. |

By mid-September 1968 all three ships had floated for several days in the Indian Ocean when a Soviet Proton rocket with the Zond 5 spacecraft roared off its launch pad in Kazakhstan. The capsule headed off towards the Moon, swung around, and hauled-ass back towards Earth. Jodrell Bank picked up a tape-recorded voice transmitted from the spacecraft, a clear indication that she was a prototype for a manned spacecraft.

Hareland writes that on the night of September 21, Zond 5 came screaming back to Earth, splashing down only 100 kilometers away. McMorris’ antennas sucked up all the radio waves that they could from the little capsule that had just gone around the Moon. The three ships fired up their engines and headed off toward the splashdown point as fast as they could. But none of them were greyhounds and they did not break any speed records on their way to the capsule.

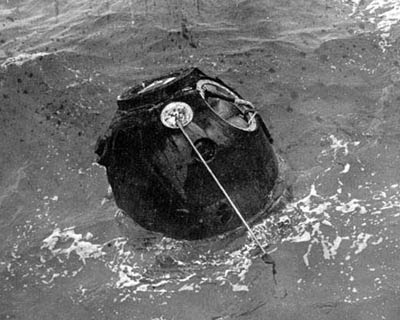

According to Hareland, on the morning of September 22, 1968, the Russians hauled the little Zond spacecraft aboard one of the ships as sailors on the McMorris photographed it. He writes that some of McMorris’ crewmen were able to take chemical and debris samples from the water.

This intelligence catch for the US Navy was an accident. According to Russian space expert Anatoly Zak the Zond 5 capsule was actually supposed to come down in Kazakhstan. But there was a problem with its braking engine and instead of a single long blast controllers hurriedly commanded it to make a series of short quick pulses and were able to direct it to a splashdown in the Indian Ocean, where the McMorris was waiting for it. Zak says that he is amazed that they were able to recover it at all, and Hareland was impressed that it came down so close to the recovery ships.

Hareland writes that Zond 6 was launched on November 10, and a day later, as the spacecraft was heading to the Moon, NASA administrator Tom Paine announced that Apollo 8 would fly astronauts to the Moon for the first time.

Space historians and journalists have long speculated about the linkage between the Zond flights and the Apollo 8 decision, although most note that the actual decision to send Apollo 8 to the Moon occurred in August 1968, and Paine’s announcement was merely the first public acknowledgement of the decision. Even today, over four decades later, that linkage between Soviet actions and the American decision is primarily circumstantial. Most of the evidence consists of either comments by the Apollo 8 astronauts, who were not actually involved in the decision itself but were told about it later, or oral histories. All of the records of the people who were directly involved in the decision point in a different direction.

The recovery of the Zond 5 capsule. (credit: NASA) |

Several years ago I tried to chase down the linkage between the Zond missions and the Apollo 8 decision for a paper I was presenting at a history of science conference. My starting point was Charles Murray and Catherine Bly Cox’s excellent 1989 book Apollo: The Race to the Moon—still the best history of Apollo ever written. Murray and Cox have a detailed accounting of the decision to send Apollo 8 to the Moon. Although they acknowledge the importance of the Zond missions, they state that Apollo manager George Low was the key figure in the decision, and his primary motivation was the Apollo schedule. Simply put, although the Apollo spacecraft and its Saturn 5 rocket were ready to go, the lunar module was not ready for the flight. Waiting for it would mean standing down the program for an extended period of time. Because Apollo was running a race flat out, pedal-to-the-metal, nobody wanted to pause the flight schedule to wait for the LM. Flying Apollo 8 around the Moon was a bold move, but NASA’s leadership considered it to be a better choice than the other options, and, as Murray and Cox wrote, NASA “needed to obtain deep-space experience in translunar navigation, lunar orbit, communications, and thermal conditions, and all that could be obtained with a crew in the command module.”

| History is rarely clear-cut and definitive because humans are annoyingly complex creatures. Often there are as many explanations of events as there are people involved in them. |

A good historian’s instinct is to never trust any historical interpretation or take any explanation at face value if you have the time and resources to check it (an instinct that has paid off in tracking down the origins of early American space policy). So I started looking in archives for information on what inputs entered into the Apollo 8 decision. But try as I might, even though I was searching nearly a decade and a half after they wrote their book, I could not find any evidence that contradicted Murray and Cox. Their research was top-notch and like the best historians, they never got out in front of their evidence and speculated about things that did not have a solid foundation in fact. The only new piece of information that I found was a forgotten NASA scheduling document indicating that the option of sending Apollo 8 around the Moon had first been proposed in spring of 1968, several months earlier than previous historical accounts had stated, and before NASA or the CIA became concerned about the Soviet Zond flights.

To date, no smoking gun has emerged that directly connects Soviet actions to the Apollo 8 decision. That smoking gun would have to consist of a statement or document directly from someone who made the decision that indicated that the reason was Soviet actions. An intelligence report alone would not be sufficient, because we already know that NASA officials were aware of Soviet actions. The intelligence information collected by the McMorris, such as the radio signals gathered by her antennas and the photographs of the Zond capsule being lifted from the water, has not been released, but it would not provide that smoking gun. After all, the Soviets themselves released photos of Zond 5 being pulled from the water.

History is rarely clear-cut and definitive because humans are annoyingly complex creatures. Often there are as many explanations of events as there are people involved in them. Historians are left evaluating sometimes conflicting evidence and making a decision based upon the preponderance of evidence. In the case of the Apollo 8 decision, the vast majority of evidence—cohesive, coherent evidence—supports the conclusion reached by Murray and Cox in 1989 that it was lunar module availability and the Apollo schedule, and not the Soviet Zond missions, that led NASA officials to send Apollo 8 to the Moon. This is not to say that the Zond missions were unimportant. They influenced the environment in which the decision was made, and probably made it harder to not fly Apollo 8 around the Moon once the agency’s senior leadership started discussing it. But NASA’s leadership already knew that they were in a Moon race, and one of the keys to winning a race is to stay focused and run as fast as you can and don’t look back to see where your competitor is. Watching the competition was the job of the little ships like the McMorris.