A bilateral approach from maritime law to prevent incidents in spaceby Michael Listner

|

| The goal of a ban on “space weapons” is a laudable one; however, the obstacles for implementing a successful accord are numerous. The largest hurdle to overcome is to define what a “space weapon” is. |

Following this, China launched Shenzhou-7 manned space flight on September 25, 2008. Among other feats, the mission featured the use of the BX-1 micro-satellite in relative proximity to the Shenzhou-7 spacecraft and within visual range of the International Space Station. The details surrounding the BX-1 are still coming to light, but there are questions to whether this may have been a test of a co-orbital space weapon considering the relative distance from the ISS or a demonstrator for satellite inspection technology. (See “China’s BX-1 micro satellite: a litmus test for space weaponization”, The Space Review, October 20, 2008.)

Enter 2009 and the January 14, 2009 article from Spaceflight Now discussing the United States’ announced capability of satellite inspection in geosynchronous orbit via the use of its two Mitex satellites and their subsequent orbital inspection of the failed DSP-23 missile warning satellite. (See “The ongoing saga of DSP Flight 23”, The Space Review, January 19, 2009.) The announcement of such a capability certainly did not go unnoticed and makes one wonder what prompted the public disclosure of such a capability if not to cause uneasiness amongst potential rivals of the United States. Regardless of the rationale for disclosure, this capability was doubtless seen by some as an escalation in an impending crisis in space.

Interestingly, not long after this capability was announced and with the beginning of a new administration in the United States, the White House went on record publicly as favoring a ban on weapons that would “interfere with military and communications satellites.” This stance on space weapons, among other deficiencies, is couched in vague terms that make it unclear what a “space weapon” is and it is unclear to what length the current administration will go to in banning “space weapons.”

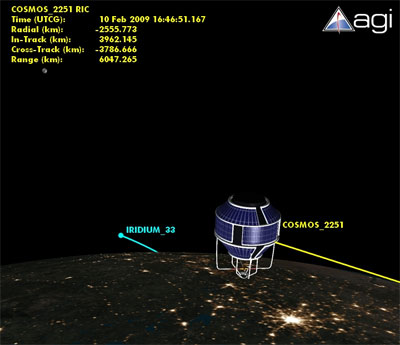

Most significantly, on February 10, 2009, Iridium 33, a commercial communication satellite owned by Iridium Satellite LLC, collided with the purportedly derelict Russian Cosmos 2251 military communications satellite 800 kilometers over Siberia. While the loss of the Iridium 33 satellite was not crippling to the Iridium satellite phone network, the resulting collision did create a debris field that potentially could interfere with future space operations. The incident has resulted in finger-pointing between Russian and American space experts who each claim that the other should have been aware that such a collision was imminent, and while the collision did not impair a high-value asset, a similar collision or secondary collision from debris from this collision with a high-value asset such as a weather satellite or other another United States satellite or spacecraft could spark a serious international incident.

Of note, this incident occurred less than a month after the article concerning the United States’ geosynchronous inspection capability was announced and less than two weeks after the Obama administration pledged to seek a ban on weapons in space. While this is not saying that the February 10th incident was a deliberate or manufactured response, the timing of this incident is interesting, at least, given recent events.

Regardless of the nature of these incidents, they all invigorate the continued efforts by various countries and groups for a comprehensive ban on “space weapons.” The goal of a ban on “space weapons” is a laudable one; however, the obstacles for implementing a successful accord are numerous. The largest hurdle to overcome is to define what a “space weapon” is. The definition is not easy because technology developed for use in space could have applications for both non-military and military applications. These so-called dual-use technologies are a hindrance to effectively defining what constitutes a “space weapon.”

For example, the maneuvering and inspection technology demonstrated by the Mitex satellites has the legitimate purpose of inspecting United States space assets. However, since the satellites are funded under a military program, it could be argued that the same technology could form the basis of an ASAT weapons platform to interfere with satellites of other nations, if not to destroy them. The question is whether to assume the worst and brand Mitex and its technology as “space weaponry” or venture that the technology’s beneficial attributes outweigh the risk of its weapons potential and not ban it as a “space weapon.”

Taking this argument a step further, the United States and the Russian Federation field the two most widespread positioning, navigation, and timing satellite systems: GPS and Glosnass. Both satellite systems are funded by each of their countries’ respective militaries, yet millions of people utilize their services in everything from ocean navigation to personal locators in cell phones. However, this same technology is also used by the military for functions ranging from passive navigation to active targeting and guidance of munitions. The question is would a definition of “space weapon” be so broad that it would encompass GPS technology and therefore be banned or at the very least restricted, or do the benefits of this dual-use technology outweigh the risks of its weapons potential?

The more recent incident of the collision between the Russian Cosmos 2251 and the Iridium 33 muddies the waters even further. Considering that the collision of the two satellites resulted in the destruction of a functional satellite and created a debris field that may deny the use of space over certain areas and orbital planes, it could be argued that satellites themselves could potentially be used as ASATs and thus be classified as “space weapons” even if their original purpose and design have no direct or indirect military utility. The question is, would a definition of “space weapon” be so broad that it would preclude or restrict future satellite launches to reduce the number of potential “space weapons” in orbit, or does the benefit of having those future satellites in orbit outweigh the risks that they may be used as weapons?

Current international space law is vague on the subject and thus not helpful in the matter either. The closest the Outer Space Treaty comes to banning space weapons is Article V, which starts off talking about placement of weapons of mass destruction in orbit:

“States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”

Article V continues in that:

“The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used by all States Parties to the Treaty exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military maneuvers on celestial bodies shall be forbidden. The use of military personnel for scientific research or for any other peaceful purposes shall not be prohibited. The use of any equipment or facility necessary for peaceful exploration of the Moon and other celestial bodies shall also not be prohibited.”

Nowhere is there a direct reference to the testing and placement of weapons other than weapons of mass destruction in orbit nor is there really a definition of a “weapon” other than nuclear devices in the Treaty. Of course, a broad interpretation of “weapon of mass destruction” could be made that considers any military spacecraft a “weapon of mass destruction” or that “peaceful purposes” excludes any military equipment or activity in space. However, without consensus on such a delineation on the definition of “weapon of mass destruction” or “peaceful purposes” these broad interpretations are unlikely to sway the major players in space.

Concurrent with the difficulties of defining “space weapon” is enforcing an agreement that bans them. Multilateral international treaties tend to lack of teeth for enforcement and abuse by parties for their own political means is possible. For example, a party to such an agreement could orbit a spacecraft that has a strictly benign purpose; but, another party to such an agreement could easily object solely for the purpose to stir controversy and for political gain by alleging that the spacecraft is a “space weapon” without offering any verifiable evidence. The accused party would be in the awkward position of trying to convince a world that has already been whipped into a media and political frenzy that its spacecraft is not a “space weapon” and that its use is strictly benign all the while the accusing party reaps the benefits of the seeds that it has sown.

Maritime precedence

Considering some of the complexities of instituting such a ban, a more effective approach is to focus on the conduct between spacecraft of differing nations while in orbit. Since it would likely be the interaction of a spacecraft of one nation interacting with another spacecraft that could lead to an international incident, an agreement outlining a set norms for the conduct of spacecraft in flight might alleviate the issue of an unintentional conflict in space. Such an agreement does have precedent in maritime law.

During the 1960s, several incidents occurred between naval forces of the United States and the naval forces of the USSR, including incidents involving aircraft and surface vessels. These incidents prompted the United States to propose talks with the USSR to prevent these incidents from becoming more serious and escalating into more serious international incidents.

| Concurrent with the difficulties of defining “space weapon” is enforcing an agreement that bans them. Multilateral international treaties tend to lack of teeth for enforcement and abuse by parties for their own political means is possible. |

The USSR accepted this proposal and after two rounds of talks, one on October 1, 1971 and the other on May 17, 1972, the Agreement known as the Agreement Between the Government of the United States and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Prevention of Incidents On and Over the High Seas was signed and entered into force on May 25, 1972. (See generally, Agreement Between the Government of the United States and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Prevention of Incidents On and Over the High Seas for a general narrative of the Agreement and its text.) The history of this agreement and the international law it is based upon is not central to this essay; however, a brief discussion of the content is in order.

The Incident on the High Seas Agreement

The recitals of the Agreement 1) express the desire to assure the safety of navigation of ships and aircraft of the respective armed forces; and 2) the guidance of both Parties to the principles and rules of international law. The recitals are followed by ten Articles, starting with Article I, which includes the definition of “ship” and “aircraft” for the purposes of the Agreement.

Article II refers to of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (see International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea), which are referred to as the “Rules of the Road.” Article II also recognizes each Parties’ right to conduct operations on the high sea according to the 1958 Geneva Convention on the High Seas.

The “Rules of the Road” introduced in Article II is not an innocuous term simply restating the two conventions that it references, but is rather used in conjunction with potential circumstances in which the armed forces of each Party may find itself while encountering the other on the high seas. These circumstances are discussed in eight separate paragraphs in Article III that concern ships (as defined by the Agreement) and by one paragraph in Article IV for aircraft (as defined by the Agreement.)

The Agreement continues with Articles V-VI, which discuss mandated signaling and navigation lighting as well as mandated warnings to other mariners of actions on the high seas that present a danger to navigation or aircraft in flight as well as the use of signals of intentions when Parties are maneuvering in proximity of each other.

The remaining articles discuss protocols for reporting incidents that occur, review of the implementation of terms, duration and renewal of the agreement and the formation of a Committee to discuss specific measures that conform to the agreement, including the practicability of concrete fixed distances to be observed during encounters between ships and ship and aircraft.

One year after the signing of the Agreement, the Parties signed a Protocol in Washington further fleshing out the terms. In particular, the Protocol discusses prohibited activities concerning non-military ships of the other Party, including aiming weapons at non-military ships and dropping objects near non-military ships in a manner that would be hazardous to ships or navigation.

Controlling conduct, not banning weapons

The intent of the Incidents on the High Seas Agreement is to regulate the conduct of the two Parties in international waters rather than prohibit weapons at sea. Incidents at sea were not predicated by the presence of warships on the high sea, but rather by the conduct of the ships belonging to the two Parties. Such is the situation we find ourselves now with the issue of space weapons. It is not the existence or presence of “space weapons” or dual-use technologies that would incite an incident, but rather the conduct and use of that technology that could lead to an international incident.

A good example is the aforementioned Mitex or BX-1 technology. While both these technologies potentially have a legitimate use under international law, their nature is such that their technology could be used to violate the sovereignty of one or more nations in space and spark an international incident. It is situations such as this that the Incident on the High Seas Agreement sought to prevent on the world’s oceans by defining the conduct of the Parties’ naval forces in relation to each other in international waters. The time has come to apply the same ideas and principles to the realm of international space law. What follows is the basic outline of what such an agreement might contain.

“The Incidents in Space Agreement”

The principles and goals of the Incidents on the High Seas Agreement are applicable to the emerging issue of space weaponry, albeit there are differences given the nature of space and the rules of present international space law. There are currently three nations with the demonstrated capacity for manned space flight and the demonstrated capacity to affect or interfere with the space capability of each other: the United States, the Russian Federation, and the People’s Republic of China.

| Incidents at sea were not predicated by the presence of warships on the high sea, but rather by the conduct of the ships belonging to the two parties. Such is the situation we find ourselves now with the issue of space weapons. |

Applying the principles and goals of freedom from interference and the prevention of incidents involving spacecraft would begin with separate formal invitations by the United States to the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China to enter into bilateral discussions concerning space operations. Because of the sensitivity and complexity of the topic, opening trilateral agreements would be more cumbersome and have less probability of producing an effective agreement given the multiplicity of varying national interests, cultural disparities, and differences in space operations. Such bilateral agreements with the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China would not prohibit—and in fact might encourage—the two nations to adopt a similar measure.

Until negotiations for such an agreement are underway, there is no certainty what it would look like; however, it would likely at least contain the following:

First, it would a recite the intent and circumstances of the Agreement to assure the safety of navigation of spacecraft of the Parties without interference. Second, it would incorporate by reference the current body of customary international space law and that which is codified in agreement through the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies and its children Treaties, all of which the three nations in question are Parties to (with the exception of Moon Treaty).

Third, it would define with particularity for purposes of the Agreement the concepts of spacecraft, aircraft, and ground station, with emphasis on including both non-military and military entities within the definitions. This, in effect, would cover all potential avenues of interference from which a Party might proceed against another Party’s space assets.

Fourth, “Rules of the Road” based on the principles of international law recited and incorporated into the Agreement would be developed. The “Rules of the Road” would discuss conduct of spacecraft in relation or proximity to each other, including placement of spacecraft in co-orbits, simulated attacks, electronic targeting of spacecraft, and the use of energy devices, including lasers, by spacecraft, aircraft, or ground stationa to illuminate or disrupt another Party’s spacecraft. The “Rules of the Road” would also discuss activities and conduct which might deny the use of space by the other party, including activities that could potentially create hazards that interfere with the transit of the other party’s spacecraft through certain orbital planes, including over flights of certain countries.

Fifth, it would create a protocol for informing the respective Parties of any activities that may interfere with the space activities of either Party. For example, if one Party was aware that a satellite or spacecraft could likely interfere with or collide with a known satellite or spacecraft of the other Party, communications would be made though the established protocol to communicate this information. The protocol would also allow a means to report an incident that has occurred so as to prevent it from escalating further.

Sixth, the Agreement would mandate the formation of a committee to consider and propose measures to support the goals of the Agreement. Specifically, the committee would discuss fixed distances between spacecraft, including those in separate orbits and those in co-orbits. The recommendations of the committee would be considered by the Parties and if agreed to would be adopted as part of the Agreement. The committee would also meet at designated intervals to discuss whether current measures to abide by the Agreement are effective and to make modifications to those measures as necessary.

| While an agreement would not guarantee that incidents would not occur through the deliberate acts of the parties individually, it would reduce the likelihood that incidents would occur through a mistake or misunderstanding and at the same time open an avenue of dialogue that may prevent deliberate acts all together. |

The Incident in Space Agreement, like the Incident on High Seas Agreement, would be designed not to restrict the nature or function of space assets, but rather to reduce the possibility that an international incident would occur through an accident or misunderstanding involving the activities of the spacecraft or to prevent an escalation of an existing incident through protocols within the Agreement. The idea is that the Agreement will create a dialogue through which the likelihood of an incident occurring or escalating will be diminished through the enhancement of mutual knowledge and understanding of each other’s space operations.

Conclusion

Bilateral accords such the Incidents on the High Seas Agreement are not designed to supplant established international law but rather to supplement it. The parties in the Incident on the High Seas Agreement took the opportunity to open dialogue and apply the existing framework of international law to further delineate existing international law on the world’s oceans to address a clear and present risk of escalating incidents on the high sea. In doing so, they diminished that risk and the potential of armed conflict as a result.

Such is the goal of the agreement proposed in this essay. By the major players in space joining in separate agreements like the one proposed, existing international space law would be further delineated to address specific conduct in space between the parties. While it would not guarantee that incidents would not occur through the deliberate acts of the parties individually, it would reduce the likelihood that incidents would occur through a mistake or misunderstanding and at the same time open an avenue of dialogue that may prevent deliberate acts all together.