2009 plus oneby Dwayne A. Day

|

| It is highly unlikely that anybody will lament that the world of 2010 does not look like the world of 2010, the movie. That is a good thing, because rather surprisingly, our 2010 does not look quite so bleak. |

His contemporary, Arthur C. Clarke, was the scientists’ science fiction author. A common theme of Clarke’s stories was man’s failure to understand a mysterious universe. It’s a theme we see again and again in his work. In Childhood’s End, human beings are evolving into a higher stage of life, and those unfortunate enough to be left behind can only envy, but not comprehend, these new lifeforms. In Rendezvous With Rama an alien spacecraft zooms through our solar system and a human crew explores it, only to find it filled with dangers and bizarre creatures… and then the craft leaves. The humans—like most scientists—are stuck with more questions than they started with.

And then, of course, there’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The movie was based upon Clarke’s short story The Sentinel, and was written by both him and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick. Their collaboration was not always amicable, but Clarke was one of the most gregarious humans to walk the Earth and gave Kubrick much credit for the evolution of the story, which Clarke also turned into a book, followed by several relatively unremarkable sequels.

2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the most maddening cinematic masterpieces ever made. It requires thought, patience, and focus, and even then it is difficult to understand. Essentially the story is this: an alien race interferes with human evolution in the distant past, enabling apes to use tools—and to kill—and evolve. Millions of years later humans encounter an alien object under the surface of the Moon near the crater Tycho. It transmits a signal to Jupiter and the humans send the spaceship Discovery to another object, a monolith, in orbit around the giant planet. Along the way, Discovery’s intelligent computer HAL kills off most of the crew before it is disabled. Finally, a lone astronaut leaves the ship to explore the monolith. The monolith is some kind of gate, or device—we never learn exactly what—that apparently transports astronaut David Bowman someplace. In the final scenes of the movie Bowman is shown living alone, growing old, and then apparently evolving into some new lifeform, the “starchild.” The fact that the audience never knows exactly what is happening to Bowman is part of the point: the alien race is so far beyond our ability to understand that we are no more enlightened than the apes at the beginning of the film.

2001, which premiered in 1968, was profound for many reasons. Beyond the mind-boggling plot, it had many other unique aspects. It was one of the first movies that attempted to tell most of its story visually, without dialogue, and without a traditional narrative; there is no protagonist or antagonist, no dilemma to be solved or princess to be saved. The music was unique and inspired. There was The Blue Danube Waltz that played as the spaceplane danced with the rotating space station, and Also Sprach Zarathustra, which symbolized the alien-assisted evolution and became iconic itself in countless movies and television commercials, symbolic for the dawn of a new age, or at least a new dishwashing detergent. One of Kubrick’s main themes was lost on many viewers: a future that was simultaneously amazing and bland and unappealing. The fantastic machines that humans built had sucked the humanity out of them, and were capable of murder. And of course the special effects were groundbreaking and the only Oscar win for the film. (If you ever needed proof that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences often makes idiotic decisions, you only need to know that 2001 lost in the best picture and best director categories to Oliver!, which has never made anybody’s list of the 100 greatest films of all time.)

Needless to say, a lot of people did not get 2001. Many prominent film critics hated it, or didn’t understand it, and the public did no better. The only people who really seemed to enjoy the film at the time were those who dropped acid right before the spectacular visual effects as Bowman encountered the monolith (and in fact, one of the movie’s promotional catchphrases was “the ultimate trip”). It took a few years, but eventually the film was recognized as a masterpiece, an amazingly frustrating and challenging one, but a masterpiece nevertheless.

There was no need to make a sequel.

The Year We Make Contact

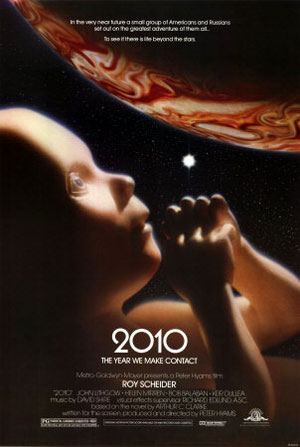

In December 1984, 2010 debuted, advertised with posters depicting the starchild and the phrase “The Year We Make Contact.” The film was directed by Peter Hyams who also wrote the screenplay based upon a 1982 novel by Clarke. Hyams was a journeyman director with over a handful of movie credits to his name, including the science fiction movie Outland and the paranoid thriller Capricorn One, which has been rumored to be slated for a remake for several years now (see “Little red lies”, The Space Review, February 19, 2007).

The story of 2010 picks up several years after the first movie. Dr. Heywood Floyd, the director of the agency that sent the Discovery to Jupiter, is now a university chancellor and astronomer, with a pretty wife and a young son. Floyd is contacted by a Russian scientist who informs him that Discovery has become unstable in its orbit and will crash before an American expedition can reach it. Floyd joins a Russian—or more accurately, a Soviet—expedition aboard the spaceship Leonov, which is traveling to Jupiter and a rendezvous with Discovery.

| Needless to say, a lot of people did not get 2001. Many prominent film critics hated it, or didn’t understand it, and the public did no better. |

On its way, the Leonov reaches Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, where the crew discovers evidence of chlorophyll, and movement, i.e. life. They soon rendezvous with Discovery, which Floyd and two other Americans reactivate, slowly bringing HAL back to life. Floyd is met by Dave Bowman, or what appears to be Bowman, who tells him that the expedition must leave Jupiter immediately. Floyd soon discovers why when he sees that the monolith has entered Jupiter’s atmosphere and is multiplying exponentially. The Americans and Soviets connect their ships together and boost away as Jupiter turns into a sun. We then see the surface of Europa, millions of years later, teaming with new life under a Jovian sun, and under the watchful presence of another monolith.

From the description above, it is easy to see how 2010 attempted to continue the story and the themes established in the earlier movie. Just as the aliens helped the apes to evolve into men, and helped Bowman to evolve into the starchild, they are now fostering the evolution of new life on Europa.

And just as 2001 was one of the most scientifically and technically accurate science fiction movies of its day, 2010 also strove for a high degree of accuracy. The film benefited from the scientific discoveries of the two Voyager spacecraft that had sped past Jupiter in 1979, as well as the latest in speculation about advanced space technology. For example, upon arriving at Jupiter, the Leonov slows down by enclosing itself in inflated Kevlar balloons and “aerobraking” in Jupiter’s atmosphere. This was a concept that had existed since the 1950s, but had been under study at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in recent years. Similarly, when the astronauts encounter Discovery in orbit around Io, it is covered with a fine layer of volcanic powder from the moon’s many volcanoes, which had been discovered by Voyager a few years before.

But of course the biggest scientific reveal was the discovery of life under Europa’s ice. The possibility that Europa could foster liquid water underneath its ice had first been proposed over a decade earlier, but it was not until the late 1970s and the voyages of the submersible Alvin that scientists realized that life could exist without photosynthesis to support it (see “The spacecraft and the submarine”, The Space Review, September 2, 2008). Last week NASA announced plans to launch a mission to Europa in 2020, reaching that enigmatic moon later in the decade. The movie 2010 was very much the product of the scientific discoveries of the late 1970s. But as we approach the actual 2010 and NASA plans a robotic mission to Jupiter, the technology, and most importantly, the money, does not yet exist.

From the ultimate trip to the ultimate struggle

There was a hint of politics in 2001. At one point in that film Heywood Floyd encounters some Russian scientists whom he deceives about the discovery of the monolith on the Moon. But that was all. Kubrick didn’t care about politics (Dr. Strangelove had plenty); he was searching for God.

In contrast, superpower politics is one of the major themes—and major weaknesses—of 2010, which was filmed during the height of the Reagan defense buildup, the dawn of the Strategic Defense Initiative, and the nuclear freeze movement. The relationship between the Americans and the Soviets is strained as their governments prepare to go to war over Honduras. The movie takes on a rather clichéd Hollywood message that the Cold War is little more than pointless ideological posturing by both sides, rather than a legitimate ideological struggle.

| Superpower politics is one of the major themes—and major weaknesses—of 2010. |

In fact, we eventually learn that HAL’s mental breakdown and the murder of most of Discovery’s crew was caused by the fact that the White House’s National Security Council ordered the super intelligent computer to lie and conceal the mission’s true goals from the crew. “The goddamned White House!” one character exclaims in disgust. This was actually a contradiction from the first movie, where we learned that Heywood Floyd was behind HAL’s deception, and it is hard to avoid concluding that director Hyams decided to go for some cheap political point scoring rather than, say, exploring Floyd’s guilt over HAL’s actions.

Even today the technology in the film holds up fairly well, although at one point Floyd is seen with an issue of Omni magazine—which folded in 1995—and an early 1980s version laptop computer. But it is the politics that make the movie so dated. Of course, as we approach 2010 there is no Soviet Union, having been tossed on the ash heap of history nearly two decades ago, and nobody is really concerned about superpower politics in Latin America. Indeed, the once vigorous, even malevolent Soviet space program is virtually nonexistent as well, barely able to mount more than one scientific space mission every five years or so, and doing little more than offering taxi rides to a space station in low Earth orbit—a space station that does not even spin, and would look silly accompanied by The Blue Danube Waltz.

Legacies

Could 2010 could have done anything to raise itself to the level of its predecessor? Few sequels are as good as their predecessors (only a few come immediately to mind: The Godfather Part 2, Aliens, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and Star Trek II: the Wrath of Khan). Unfortunately, 2010 does not even try. It would have been a better and less dated film if the political subplot had been removed. But it still would have been largely unworthy as a sequel to one of the greatest films ever made. It could only have been great if Stanley Kubrick was involved, and Kubrick did not make sequels, he made art.

| 2010 is boring in the way that virtually all science fiction films set in the near future are boring. 2001: A Space Odyssey is boring in the way that a symphony can be boring for people who do not listen to symphonies. |

2010 is not a bad film. It is competently made, and features adequate acting, decent special effects, relatively high production values (Syd Mead, who also worked on Blade Runner, designed the spacecraft), and a minimal and forgettable soundtrack. But it is boring. Unfortunately, it is not boring in the way that 2001: A Space Odyssey is boring. 2010 is boring in the way that virtually all science fiction films set in the near future are boring. Lacking lasers or starships or Michael Bay’s explosions or Will Smith punching an alien in the face (“Welcome to Earth!”), it is difficult, nigh impossible to make a movie that is technically and scientifically accurate and yet riveting to watch. Those of us interested in spaceflight and seeing our dreams projected on the screen wish it was not so, but there is too much evidence to the contrary. The near future is too much like the present, and the parts of the present that are not boring—the economy, Iraq, terrorism—are not entertaining, they’re scary.

2001: A Space Odyssey is boring in the way that a symphony can be boring for people who do not listen to symphonies. If you do not appreciate the artistry, if you lack the patience and the commitment and the soul for the subject and the message, there is a good chance the masterpiece will put you to sleep.

But even if you do possess all of these things, 2001 is so unlike what we expect from movies that it is difficult for us to transform into the kinds of beings that can appreciate its artistry. Its very existence is contradictory, because although you will always notice new things upon repeat viewing, you rarely want to invest the effort to do so. It is hard not to imagine Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke standing at the side of the screen chuckling at all the apes staring at their creation, trying to understand God.