How should we secure our space-based assets as a nation?by Christopher Stone

|

| It appears the Russians and Chinese are moving (and have been for many years) towards weaponizing space, but they are blaming the US falsely for doing it first as their excuse. |

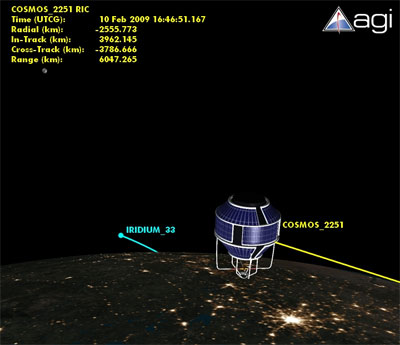

At the same, US satellites, military as well as commercial, have been dropping offline in space. There is also the case an Iridium satellite and a defunct Russian satellite colliding in orbit, creating yet another band of space debris in orbit around our planet. All throughout these situations, the United States has been the one nation that has been blamed for developing space weapons and planning to create a sort of “space hegemony” according to one author in Air and Space Power Journal. At the UN, the US has been lambasted by Chinese and Russian officials stating that their security is being threatened by the US because of our discussions about space weapons threats to our satellites and the need for increased space situational awareness of our national security and commercial space infrastructure. They also point to the National Space Policy created in 2006 by the Bush Administration as creating the framework to create such a “space hegemony” whereby other nations would cease to have access to space. This is simply not the case.

US government officials have stated numerous times, categorically, that there are no space weapons programs being funded by Congress. Yet, the Russians and Chinese both have stated that the only reason they are developing their space weapons is to defend themselves against the US deployment of weapons, weapons that according to many government officials, past and present, are not even being planned, much less deployed. Despite reassurances of quite the opposite, General Popovkin, the Russian Deputy Defense Minister gives the impression that the Russians, while developing their own space weapons systems are just defending their interests. “Russia has always been for non-deployment of weapons in space, but when others are doing this, we cannot be just onlookers, and such work is underway in Russia. This is all I can tell you.”

By reading reports in the press such as these, as well as decades of Russian and Chinese open source planning and doctrine papers from their government diplomatic and war colleges, it appears the Russians and Chinese are moving (and have been for many years) towards weaponizing space, but they are blaming the US falsely for doing it first as their excuse. This tactic is called “projection”. Moreover, they are very effectively luring the arms control community into blaming the victim. The United States is dependent on satellites for our security, economy, and our ability to project power around the globe, and they know it. They are no where near as dependent on space as we are and they are knowledgeable of that, too. The Obama Administration must seriously question the wisdom of entering into space arms control agreements of any kind with Russia and China when they may be engaging in a campaign of deception designed to trick the US into signing treaties that leave our space systems and their users completely vulnerable. In other words, they seek only to constrain US power and are exploiting the good intentions of the arms control community and the American people to help achieve their ends.

This approach is not new, and the Russians and Chinese are counting on the naiveté of the new administration to fall for it. If space arms control measures are adopted, the only option US strategists will have to protect the nation from “illegal” attacks on its space systems will be a transfer of capability from space to terrestrial alternatives and abandoning most of the current security and commercial space sectors. This will result in a significant contraction of the overall national space program and the space industrial base that supports it. That means job losses and a reduction in America's aerospace industry—our most successful economic sector—at a time when job security is scarce as it is.

So, with all of this background information in mind, it comes as no surprise to this author that arms control advocates as well as members of the Russian and Chinese space forces are elated to see that the Obama Administration is working toward a worldwide ban on space weapons. If this agreement can just be made among the spacefaring countries of the world, peace will return to the heavens and the theory of space as a sanctuary free from conflict will be restored. Or will it?

| Any satellite can become a weapon if desired. They don’t have to be equipped with lasers or tungsten rods. |

There are many other reasons to steer clear of arms control agreements regarding space. One reason is the fact that there is no clear definition of what a “space weapon” is. The term space weapon could possibly be applied to terrestrial-based systems, both defensive and offensive, that are necessary parts of our national defense strategy and architecture. A few examples of this are missile defense interceptors and ICBMs. Last year, the United States made an agreement with Poland and the Czech Republic to base ground-based missile defense interceptors and a radar to increase the reach of our layered, ground-based missile defense system against nations such as Iran in addition to systems already in place to defend against such an attack by North Korea. These missiles reach into space to intercept missiles during their mid-course phase of flight and as such could be considered a space weapon by some countries. Our Navy Standard Missile 3-equipped ships could also be considered a space weapon by some because these missiles have shown to be adaptable (once) to intercept satellites in low Earth orbit.

ICBMs, a key piece of our nuclear deterrent force for over fifty years, flies through space on a ballistic flight path toward its target on Earth. This capability could also be outlawed by such a ban on space weapons. While the language on the White House website states that the ban will be on weapons that “interfere with civil and military satellites” some could interpret these systems (ICBMs and missile defense systems) as capable of “interference” because of the ability to adapt them to hit satellites in orbit, regardless if they were designed for this purpose or not.

What about space situational awareness programs, satellite systems that would be launched to monitor the surrounding areas near critical space systems? Could these be considered a threat to other nation’s satellites? Could satellites already in orbit be considered space weapons? The answer is yes. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union worked on what they called co-orbital ASATs where they would launch a satellite into space in order to rendezvous with another and crash into it, thereby destroying its functionality. Another aspect is the concept of using satellites as space mines. An old satellite that is no longer serving its purpose can be turned off, only to be turned back on later in order to strike other satellites.

| Acting to create a treaty to mitigate the creation of space debris for nations to have a safe place to operate their vehicles would be a much better way to increase international goodwill and security of spacecraft than an outright ban on an idea that has yet to be properly defined. |

So while treaties, agreements, and codes of conduct to prevent space from becoming a battlefield sound great, they aren’t practical or verifiable without shutting down the commercial and military space programs of the United States and all other nations in the process. Any satellite can become a weapon if desired. They don’t have to be equipped with lasers or tungsten rods. This is one reason why this author believes the Bush Administration did not sign onto any agreement banning space weapons or increasing the reach of the Outer Space Treaty. They wanted to preserve the ability of the US to defend itself, per its authority in the US Constitution and the inherent right of self-defense established in the UN Charter. This allows the US to deploy missile defenses, keep their deterrent forces up, and launch space systems to allow American space forces to monitor the condition of our satellites.

The Russians and Chinese doctrine documents view space weaponization and warfare as “inevitable”. The notion that a treaty will keep weapons out of space or satellites from being used as weapons is a bit naïve. Everywhere man has been—air, land, sea, and most recently cyberspace—have always seen conflict. Everywhere commerce has taken place, there has been conflict. To sit back and wait for our space vehicles to be attacked before acting to defend ourselves as a country is flirting with disaster. Ronald Reagan, quoting a political scientist, once said to the effect that “Countries that sign on to treaties without keeping their hardware up don’t stick around long enough to write many more.” For the United States to truly keep its space security sound, we need to hold fast from signing any treaties like the ones proposed so far.

However, acting to create a treaty to mitigate the creation of space debris for nations to have a safe place to operate their vehicles would be a much better way to increase international goodwill and security of spacecraft than an outright ban on an idea that has yet to be properly defined. Signing a ban on space weapons or a code of conduct, as fluid as the definition of space weapons is, could tie our hands with respect to our overall defense strategy and put our people, economy, and spacecraft more at risk than we are today. I hope that the President’s staff recognizes this problem and finds a better policy than supporting an international treaty banning space weapons.