Lost over the horizon: Discoverer 1 explores Antarcticaby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The North Korean regime is lying and not interested in the truth. But if they were, they could have taken a lesson from the United States and its early experience with launching spacecraft over five decades ago. |

This launch was called “Flying Yankee” and it took place from the same concrete launch pad that Discoverer Zero had occupied a month before. The whole rocket vehicle weighed 113,902 pounds (51,665 kilograms) on the ground. The Discoverer satellite, including its Hustler upper stage that served as both the rocket’s second stage and support for the payload in orbit, was eighteen and a half feet long and weighed almost 7,200 pounds (3,265 kilograms). Of the total hundred and fourteen thousand pounds on the launch pad, only 1,474 pounds (669 kilograms)—or one tenth of the initial weight of the rocket—would reach orbit. Before the launch, Lockheed’s engineers calculated that the Hustler was still too heavy. They needed to cut down weight. So they went after the vehicle with tin-snips. They cut notches into the aluminum braces and beams, removing as much metal as they could get away with without reducing the overall strength of the structure. They piled this metal on a scale and figured out how much weight they had removed and re-did their calculations. The vehicle would make it into orbit. Barely.

Like the earlier launch attempt, there was no reentry vehicle on this flight. The Discoverer instrumentation consisted of an S-band radio beacon which accepted command signals from the ground and responded to coded radar signals for long-range tracking, a VHF continuous-wave acquisition beacon for identification and ground control tracking, and a 15-channel FM telemetering system carrying a total of 97 in-flight instruments. The basic power source for the instruments and communications system was three silver peroxide-zinc batteries. The Thor’s telemetry system also relayed 34 booster performance measurements to the ground.

Although Discoverer 1 was not intended to be recovered, later spacecraft would be and so the recovery team was using the mission as a chance to practice a simulated recovery over the Pacific Ocean. This force consisted of eight C-119 aircraft, four RC-121D radar aircraft, and one B-47, all flying out of Hawaii. The Navy also provided three destroyers to patrol the ocean.

The Discoverer 1 vehicle—consisting of Hustler number 1022 and its payload—had been mated with Thor number 163 on February 23. Two days later the initial countdown began at six in the morning and proceeded to Thor pressurization during the final minutes of the countdown, just past one in the afternoon. The majority of the countdown, from T-405 minutes to 15 minutes before launch, was devoted almost entirely to Lockheed work on the Hustler upper stage vehicle and Discoverer payload. Only in the last 15 minutes before launch would the countdown involve the Thor. The Thor missile, after all, was designed to be launched in 15 minutes during a nuclear attack, so it did not require much babysitting. But there were problems with pressurizing the liquid nitrogen in the first stage of the Thor and so the countdown was scrubbed. Douglas personnel drained the booster, corrected the pressurization problem, and accomplished necessary re-checks. They were preparing to reschedule the countdown for the next day when they discovered a leak in the Thor fuel system. This put the launch off for 48 hours.

On February 28 they started again, this time at eight in the morning with an abbreviated countdown. At forty-nine minutes, sixteen seconds after one o’clock in the afternoon, the rocket lifted off the pad, its one main and two vernier engines producing 152,000 pounds (676,000 newtons) of thrust. The booster rolled to the correct azimuth of 182 degrees, 48 minutes. After 10 seconds of vertical flight, the booster pitched over on its trajectory, heading south down the California coast. Reporters watched from a sand dune two miles away.

| “When it goes over the horizon, everything is lovely. And so the Air Force holds a big press conference and says, ‘Discoverer 1 is in orbit.’ Unfortunately, the tracking stations never hear it… nor does anybody else. But we’ve already said it’s in orbit,” Buzard said. |

The Thor main engine burned for 160.75 seconds, which was about three seconds longer than planned. The vernier engines continued for 9.05 seconds after main engine cut off before they too shut down. At two minutes, 41 seconds after launch, the Subsystem “D” timer inside the Hustler turned on the inertial reference gyroscopes. Ten seconds later, the timer fired the explosive separation bolts, activated the pneumatic control system, commanded jettison of the nose cone, and ignited the retro-rockets in the adapter between the two vehicles. This caused the Thor to drop away from the Hustler.

The Hustler then pitched to a horizontal attitude. The horizon scanner activated and its shroud ejected. At 321 seconds into flight, the “D” timer activated the hydraulic control system and fired the ullage rockets a second later. These small solid propellant rockets pushed the Hustler away from the dead Thor. As the Hustler accelerated, the fuel in its propellant tanks settled back to the rear so that it could flow through the valves to the Bell engine. Seventeen seconds later, the Bell main engine fired with 15,150 pounds (67,400 newtons) of thrust.

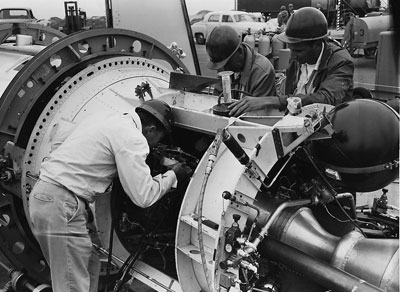

Technicians preparing an Agena upper stage—then known as the Hustler—for launch sometime in 1959. (credit: USAF) |

The engine was scheduled to fire for 96.3 seconds until it exhausted all of its propellants. Shortly thereafter, the hydraulic system that steered the engine was supposed to shut down and the propellant tanks vent any remaining gases. The vehicle was then programmed to slowly pitch down 90 degrees—pointing its nose toward the ground—in a maneuver that took just over two minutes. At this point it was supposed to vent its helium tanks, which were used to steer the engine. Finally, the “D” timer was supposed to send a command to the telemetry system at 455.5 seconds, which calibrated it. That was the plan.

At 510 seconds—or eight and a half minutes—all contact with the vehicle was lost. Based upon their initial calculations, Lockheed engineers determined that the vehicle should have entered an orbit of 605 miles by 99 miles (974 by 159 kilometers). But that was not what happened.

Frank Buzard, an Air Force officer in charge of the Discoverer launch program, explained: “The Air Force announced that it was in orbit based on tracking and telemetry data from Cooke Tracking Station, but it never showed up at the Alaskan or any other tracking stations.” Tracking objects in space was not easy. The United States did not yet have many radars that peered into space looking for objects. There were a few systems that involved sending a beam of radar signals out in a “fan” into space. Anything that passed through this beam—or “cut the fan”, as they said—would show up on the radar screen. But usually tracking was accomplished by picking up the faint radio signals of an object in orbit. None of the tracking stations ever picked up the signals.

“When it goes over the horizon, everything is lovely. And so the Air Force holds a big press conference and says, ‘Discoverer 1 is in orbit.’ Unfortunately, the tracking stations never hear it… nor does anybody else. But we’ve already said it’s in orbit,” Buzard said. Discoverer 1 should have been beeping overhead. It should have done so for 13 days according to Lockheed’s calculations. But it was not beeping. And it was not showing up on radar.

“I was one of a committee of three to determine if it went into orbit,” Buzard explained. “There was some data from Jodrell Bank that some object passed through their fan at about the right time, and also from some radio astronomers that they saw some ionization tracks at about the right times which could be interpreted to be Discoverer 1.” The Air Force had announced that the satellite went into orbit and Buzard and his cohorts had essentially been ordered to prove that the satellite was in orbit—demonstrate that the Air Force was not lying. So they took the data that supported this conclusion and used it. But Buzard did not really trust it. “I suspect that they saw what we wanted them to see,” he said.

“And then we go back and look at the facts,” Buzard explained. “And the facts are that our tracking station got only about half of the Hustler burn.” Lockheed didn’t really have good telemetry from the final parts of the rocket burn, when it was supposed to burn out, vent its propellant tanks, pitch nose down, and vent its helium tanks. “It could only track it halfway, and it assumed that since everything was right halfway, everything continued to be right the rest of the way.”

| Buzard noted that the program learned a lesson: telemetry was important. They needed better telemetry during launches. After Discoverer 1 they would not repeat that mistake again. |

“Well, that’s a bad assumption,” Buzard stated bluntly. It was entirely possible that something had happened in the second minute and a half of the rocket’s burn. Maybe the engine sputtered out. Maybe it pitched over to one side and sent the vehicle in the wrong direction. There was a very small margin of error and if the slightest thing had gone wrong with the engine the vehicle never would have made orbit. “And so we learned that you never say you’re on orbit until you get acquisition at a tracking station. So we never did that again.”

Lockheed predicted that Discoverer 1’s orbit was good for 13 days. But for 13 days nobody saw it—not on radar and not as a little bright light crossing the sky. “We spent three weeks trying to prove that it went into orbit, and I’m convinced,” he paused, “I signed the report that said it went in orbit, but I’m really convinced that it went in the South Pacific.”

As a “success” the launch was nearly useless, for the engineers got no data on how the spacecraft performed in orbit. They had learned that the Hustler would separate from the Thor and that its engine could ignite in flight. But that was pretty much it. Buzard noted that the program learned a lesson: telemetry was important. They needed better telemetry during launches. After Discoverer 1 they would not repeat that mistake again. “And we got a jillion airplanes and a whole buncha ships, and we put ’em out in the ocean from Kodiak down to Hawaii, so that they could read this stuff as the thing came back,” he said.

Something else happened during the flight of Discoverer 1. An East German radio station blasted the United States for placing a military satellite into orbit “without even talking to other states over whose territories the Discoverer is to perform espionage services.” Discoverer 1 was not a spy satellite. In fact, it was not even in orbit. But that was largely immaterial. At the time, the American leaders tended to assume that the Soviet Bloc spoke with a unified voice, so that a propaganda blast from an East German radio station might have come from the Kremlin itself.

But unlike the U-2 overflights, there was no official Soviet protest, not even in secret. The Soviets would have a hard time making a case, for they had already launched eight objects into orbit themselves, most of which had flown over the United States at some point. Discoverer was a military satellite, but it was a harmless engineering and test satellite, nothing more. And the United States had certainly been more open about its space program, including Discoverer, than the Soviets had about their program. The lack of a loud response from the Soviet government was actually a positive sign—maybe the Soviet Union would not try to shoot down American spy satellites like they had been trying to shoot down the U-2, and would eventually succeed a year later.