Doing more for less (or the same) in space scienceby Jeff Foust

|

| “The easy things have been done,” Weiler said, noting that complex “flagship” missions now cost over $1 billion. “A billion dollars doesn’t buy much any more.” |

The budget outline is vague when it comes to space science, saying that NASA will send “a broad suite of robotic missions to destinations throughout the solar system and develop a bold new set of astronomical observatories”, language which doesn’t suggest any major change in direction for the agency. The increase in NASA’s overall budget could translate into an increase for space science, although there’s certainly no guarantee. Moreover, any increase in 2010 could be a one-time affair, as the administration’s “out-year” budget projections call for effectively flat NASA budgets for the next several years.

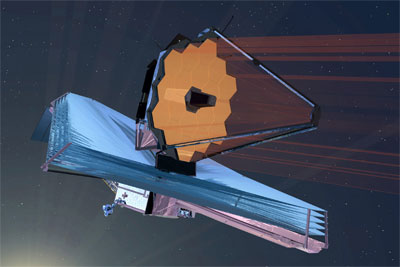

At the same time, NASA has been dealing with major cost issues with some of its space science programs, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL), the latter of which suffered cost increases and schedule delays that will cause it to miss its planned launch window later this year, further increasing its costs. Tackling those challenges are key to whatever level of funding space science gets in 2010 and beyond.

Estimation and cooperation

Some efforts at getting the most out of NASA’s space science budget are already underway. Ed Weiler, NASA associate administrator for space science, said at a town hall meeting in Los Angeles last Thursday organized by local chapters of the AIAA and National Space Club that NASA is putting a stronger emphasis on better cost estimation. He noted, for example, that former NASA administrator Mike Griffin had directed him and other NASA officials that all programs should be funded at the 70% confidence level, an effort that has just now been completed for all the programs in Weiler’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD). “That’s good news, but it’s also bad news, because when you budget appropriately, it means you do less programs,” he said. “In other words, you stop trying to fit ten pounds in your five-pound bag.”

A more rigorous approach to cost estimation will also be used in the upcoming decadal surveys in astronomy and planetary science, where scientists prioritize their top missions for the coming decade based on scientific merits and cost. Past decadal surveys have yielded cost estimates for some missions that were wildly below what NASA ended up spending on them, a process Griffin called “undercosting” in a speech three years ago. The last astronomy decadal survey, published in 2001, ranked JWST (then known as the Next Generation Space Telescope) as the top scientific priority, with an estimated cost of $1 billion. JWST’s current estimated cost, including operation of the telescope after launch, is now about $4.5 billion.

Weiler hopes to avoid a repeat of that in the latest decadal surveys. “In the past, scientists would come up with great ideas and be very optimistic about them, and do the human thing and come up very optimistic costs,” he said. This time around, Weiler said that NASA recommended to the National Academies, who run the surveys, to include engineers, program managers, and cost estimators on the survey committees. The committees will also get independent cost estimates for proposed missions. In addition, Weiler said that no mission proposals submitted to the decadal surveys from NASA centers would be “blessed” by NASA Headquarters until it does its own estimate of each project’s cost.

Better cost estimates, though, only deal with part of the problem. As NASA’s missions become more sophisticated, from flybys and orbiters to landers, rovers, and even sample return missions, their costs spiral upward even when properly estimated. “The easy things have been done,” Weiler said, noting that complex “flagship” missions now cost over $1 billion. “A billion dollars doesn’t buy much any more.”

One way to deal with these higher costs within a relatively fixed budget is to rely more on international cooperation. Weiler recounted a conversation he had last year with his counterpart in ESA, David Southwood, who was having similar problems squeezing ambitious science missions into a limited budget. “The scientists in Western Europe and the scientists in the United States tend to have the same scientific goals,” Weiler said. “We could have one hell of a great Mars program if we did it together.”

The result is a shift towards a joint US-European Mars architecture, as well as an agreement announced earlier this year for NASA and ESA to work together on a joint Jovian system mission tentatively planned for launch in 2020. The two may also cooperate on the Joint Dark Energy Mission, a proposed mission to study dark energy in the universe. “The future is going to be more international cooperation, not less,” Weiler said.

| “The scientists in Western Europe and the scientists in the United States tend to have the same scientific goals,” Weiler said. “We could have one hell of a great Mars program if we did it together.” |

Weiler said that some problems that drive up the cost of NASA science missions are beyond his control. “When I list the ten top problems at SMD, do you know what the first three are? It’s like real estate: access to space, access to space, access to space,” he said. In addition to high launch costs, he said launch delays drive up the cost of missions like Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), both of which have been delayed because of changes in launch schedules for the Atlas 5 rocket beyond NASA’s control. “Our science missions are the lowest priority there is,” Weiler claimed, ranking below both Defense Department missions and the rare commercial launch. “So SDO and LRO just get delayed and delayed and delayed” at a cost of $5 million a month for SDO alone.

Dealing with risk

Another approach to dealing with cost would be to accept a higher level of risk: the use of new technologies, lower levels of redundancy, or other approaches that reduce a mission’s overall cost but increase the odds of a mission failure. That may be attractive to some, but clearly not to Weiler.

“We could fly a billion-dollar Europa mission,” Weiler said, taking on a higher level of technical risk, “and that might be the right way to go, but not in the country I live in. Because it doesn’t depend on whether it’s a $100-million or a $5-billion program, if it fails you’re going to be in front of Congress.” Later, borrowing a line from Apollo 13, Weiler said, “Failure is not an option.”

Later in the town hall meeting Weiler defended that aversion to risk when pressed by panel moderator Robert Dickman, executive director of the AIAA. “This country has always accepted failure,” Dickman said. “Not in Congress,” replied Weiler. “Not the one I deal with inside the Beltway.” Weiler said he agreed “philosophically” with the idea of accepting more risk on science missions, but that clashed with the realities of dealing with Congress and reporters “throwing out questions about when you stopped beating your wife” when failures happen.

Dickman responded with a question: if the outcome of a failure is the same—in terms of reaction from Congress and the media—regardless of a mission’s size, should LRO get the same amount of scrutiny as Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), a smaller, less expensive secondary payload flying to the Moon with LRO? Weiler admitted that NASA was taking more risks with LCROSS. So, Dickman responded, failure is an option after all?

“Well, let’s see,” Weiler said. “What do you think the New York Times and the Washington Post will concentrate on if LRO returns beautiful images but our attempt to look for water in a crater fails? What do you think will get the front page?”

Weiler said he based this on his own experience, particularly with the Hubble Space Telescope and the reaction after its 1990 launch of flawed optics. “NASA was almost closed down,” he claimed.

| “This is the most exciting time to be at NASA,” said Worden. “Although we have budget issues, we’ve always had budget issues.” |

However, Weiler and others at the town hall meeting agreed that it is acceptable to take on higher amounts of risk for some very low-cost missions. “There is a threshold below which you can do things” without overly worrying about the repercussions of failure, Pete Worden, director of NASA’s Ames Research Center, said. He cited nanosatellites, spacecraft with masses on the order of 10 kilograms and costs of several million, as one example. Ames has experimented with several such spacecraft, including one, PharmaSat, scheduled for launch Tuesday night as a secondary payload on a Minotaur rocket carrying a military satellite.

“It’s a disappointment when it doesn’t work,” Worden said, but it’s outweighed by the benefits success can bring, including getting a new generation of scientists and engineers involved. The challenge, he said, is finding that cost threshold below which such missions can be attempted without concerns about the public and political reaction if it fails.

Despite the challenges of cost and risk, people like Worden were optimistic about the future. “This is the most exciting time to be at NASA,” he said. “Although we have budget issues, we’ve always had budget issues.”