Why is it so hard to go back to the Moon?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| To paraphrase Oscar Wilde’s Lady Bracknell, “To lose one Moon mission may be a misfortune, to lose fifty years’ worth looks like carelessness.” |

The original mission was the result of a number of factors that came together at the right place at the right time. First of all, there was the political context: John Kennedy had been elected partly of the basis of the “Missile Gap” caused by the fact that the Soviets had been the first nation to launch a satellite. Also, he had been humiliated by a number of early failures, notably the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and the retreat from Laos. Then, on April 12, the USSR launched the first man into space; the US President had to respond.

There was also the technological element. Wernher von Braun and his team had been working on the F-1 engine, the most powerful rocket engine ever built. Without this capability the US could never have even contemplated build the Saturn V Moon rocket. Kennedy’s advisors, even the ones who were reluctant to endorse the Moon program, knew that the US was far ahead of the Soviets in electronics and in materials science. They accepted that while the Russians could beat the US in the near term, thanks to the powerful R-7-class launchers that remain to this day the basis of their human launch system, they could not go beyond that.

So when Kennedy announced that America was going to “land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth” he was making a promise he was confident the US could keep. Keeping the Apollo program on track after that was largely a matter of politics and budgets. The November 1963 assassination gave the program an aura of a sacred duty to Kennedy’s memory. It also elevated Lyndon Johnson, the greatest space enthusiast ever to occupy the Oval Office. It was in those years that NASA came to absorb almost three percent of the US federal budget. (Today it receives a little more than one half of one percent.)

The Moon landing happened not on Johnson’s watch but during the first year of the presidency of the man Kennedy had beaten in 1960, Richard Nixon. While he was relatively indifferent towards NASA, members of his staff were actively hostile. The US civil space budget, which had already been cut drastically in 1968, was cut again and again during the 1970s. In spite of Ronald Reagan’s support for space exploration he failed to increase the space agency’s funding. George H.W. Bush tried to launch a program that would take America “back to the Moon and on to Mars” but the Democrats in Congress refused to go along.

| It seems certain that within the next two decades another human being is going to set foot on the Moon. |

Under Clinton NASA was not even allowed to mention the words Moon or Mars in the context of their exploration plans so they had to create a euphemism: “accessible planetary surfaces”. After the February 2003 Columbia disaster, George W. Bush allowed NASA to come up with a Vision for Space Exploration that was to be “sustainable and affordable”. Twice now large bipartisan majorities in both houses of the Congress have voted in favor of this project, which may land on the Moon in 2020. However, it now faces considerable scrutiny from the Obama Administration, Congress, and the recently formed Augustine Committee, which is studying this project and the alternatives (see “Constellation and its challengers”, The Space Review, this issue).

The Soviet Union, of course, never was able to put a cosmonaut on the Moon. Their giant N-1 Moon rocket failed in all four launch attempts. More recently, the Russians have proposed to launch a tourist flight that would circle the Moon, but not land. This trip is offered at bargain rate of $100 million.

China has announced that they are interested in landing a taikonaut on the Moon sometime between 2025 and 2030. India has also said that they are planning a Moon mission.

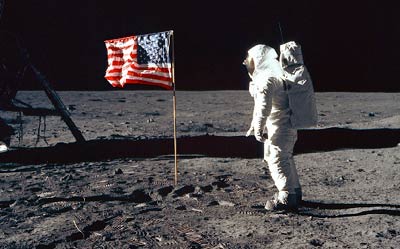

It seems certain that within the next two decades another human being is going to set foot on the Moon. Whether it will be just a “flags and footprints” mission, as Apollo is often described, or whether it will be the first step towards building a true space-based human civilization is still an open question. The US plan includes a permanent lunar base with a place for international partners, to be used for exploration, technology development, and science.

For the safety of all involved it would be best if more than one nation were to have a system that could take people to and from the Moon’s surface. It may even turn out that the best way to go back and forth is to fly commercial. A number of firms are now taking the first steps towards building cost-effective, profitable ways of getting objects and people from the surface of the Earth to the surface of the Moon.

It’s been far too long since any human visited the place.