Apollo and America’s Cold War (part 2)by Taylor Dinerman

|

| The term “soft power” had not yet been invented, but Johnson knew that the Moon program would, if properly handled, be a great and enduring positive contribution to America’s image in the world. |

Unlike most men and women who achieve high office, LBJ never had his imagination surgically removed. Most politicians know that if they appear to be comfortable talking about real new ideas, rather that just using the words “New Ideas” as a slogan, they open themselves up to ridicule and derision. In different ways, this is what happened to Newt Gingrich and Al Gore. Johnson was a believer in the possibilities of technocracy to transform the world from the inner cities of America to the rice fields of Southeast Asia, but for the most part he was smart enough to hide it. He knew, in his heart, that smart men of goodwill with enough know-how and resources could build an ideal world, one based on the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

The Apollo program was the centerpiece of this ambition. FDR’s Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which provided electricity and fertilizer to a major part of the impoverished South, and later provided explosives, conventional and nuclear, for the war effort, was the political model. He saw NASA as a new TVA that would bring education, jobs, and development to parts of the country like Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Virginia, California, and Ohio that were (with the exception of California and Ohio) reliably Democratic.

Above all the Moon landing would be his legacy, though he shamelessly used the memory of the martyred JFK in order to gain his party’s support for the program. Above all he had been, from the moment the Russians launched Sputnik, a strong believer in the importance of space. As one English author put it, “Johnson was the only American President to be genuinely interested in the space program, rather than tolerating it for political expediency.” He never made it explicit, but it is possible that he saw a future Moonbase as a celestial outpost of Rooseveltian America.

Because it was a Cold War program he did manage to muster a good deal of Republican support for Apollo as well. It was a raw but nonviolent and nonmilitary assertion of American technological and economic power, something that at the time most Republicans and most Democrats could agree on. However Johnson wanted it to be more than that.

The term “soft power” had not yet been invented, but Johnson knew that the Moon program would, if properly handled, be a great and enduring positive contribution to America’s image in the world. He had seen the way the Soviets had been able to translate their space achievements into political prestige, and knew that given the chance America could do even better. However, both JFK and Johnson hoped that they would be able to leverage the program to help improve overall relations with Moscow. In early 1964 NASA Administrator James Webb wrote to LBJ, “On balance the most realistic and constructive group of proposals which might be advanced to the Soviet Union with due regard for the uncertainties and limitations… relates to a joint program of unmanned flight projects to support a manned lunar landing.” The joint program never happened, it would not be until the Nixon-Brezhnev summit of 1972 that a serious joint space project was agreed to.

In the long term US openness about the Apollo project paid off. While the world could see both successes and failures, the Apollo 1 disaster being the most obvious example of the latter, the Soviet lack of transparency did nothing to improve Moscow’s image. Gradually the US moved ahead of the Soviets both in real terms and in global perception.

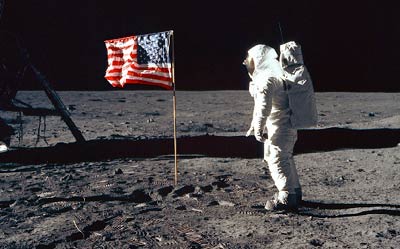

| At a time when the US seemed to be coming apart due to the stresses of Vietnam, race riots, and radically shifting social and cultural norms, the Apollo program showed the world the underlining strengths of the nation. |

Sadly by then the political impetus that LBJ had so carefully built up was largely gone, partly a victim of the program’s success—even before the Moon landing the program had demonstrated that the US could catch up with the Soviets—and partly due to Vietnam. Indeed the critical cuts in NASA’s budget came in the spring of 1968 right after the Tet Offensive. Later, LBJ told Wally Schirra “We have this great capability, but… we’ll probably just piss it away.”

Nixon was not a NASA enthusiast, not by a long shot, but neither was he blind to the international implications of Apollo. In his January 1969 inaugural speech he said, “As we explore the reaches of space, let us go to the new worlds together—not as new worlds to be conquered but as a new adventure to be shared.” When it came to high sounding meaningless political rhetoric Nixon (and his speechwriters) could keep up with the best.

The Apollo team tried to take this seriously and the result was not just a batch of miniature flags the were taken along on the Moon landing mission, but more significantly the plaque on the lander that proclaimed “We came in peace for all mankind.” A powerful propaganda gesture that did nothing to hide the American nature of the achievement.

At a time when the US seemed to be coming apart due to the stresses of Vietnam, race riots, and radically shifting social and cultural norms, the Apollo program showed the world the underlining strengths of the nation. Oddly enough this message may have been transmitted most effectively not by NASA or by any other part of the US government but by a wildly successful television sitcom; “I Dream of Jeannie” The adventures of an astronaut and his wacky Baghdad-born Jeannie not only presented a weirdly reassuring vision of NASA and of the US to the world, but helped to humanize the whole process. The show was dubbed into many foreign languages and broadcast worldwide.

It is suitable therefore for all of us to remember that forty years ago, a couple of weeks before Apollo 11 lifted off, Barbara Eden, the actress who played Jeannie, gave Buzz Aldrin a bon voyage kiss. In that moment two mighty aspects of America’s soft power briefly touched one another.