The crucible of manby Andrew Weston

|

| British ventures in space, with certain exceptions like as the failed Beagle 2 Mars landing, have focused less on prestige projects and more on those with a more tangible prospect for economic gain. |

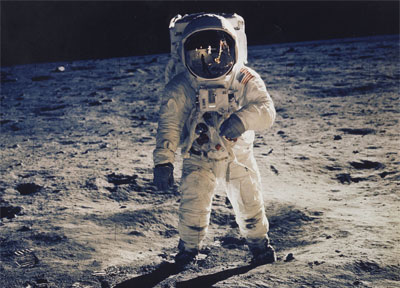

This spirit exemplifies the generosity of many former NASA astronauts and is perhaps encapsulated in the title of the 1989 documentary featuring a collage of footage from the Apollo missions: For All Mankind. It has enabled a great many commentators and space science academics in other countries, such as the UK, to talk in terms of “us” and “we” when referring to returning to the Moon and exploring beyond. Yet the vast bulk of effort, energy, innovation, inspiration, and money invested into achieving arguably most of the dramatic feats in space has come from Americans and American agencies. That is not to say there is a case for greater recognition of the efforts of Britain in space over the decades, most of all by people in the same country. Examples might well include the pioneering research with the Skylark sounding rockets in the late 1950s, the existence of agencies such as the Rocket Propulsion Establishment, and the creation of a satellite-launching rocket technology in Black Arrow that was simply abandoned to the misty stretches of time by the successive governments and British media. Nevertheless, in spite of regular contribution of instrumentation to international space missions and satellite construction over the past few decades, it is arguably only because of the magnanimous attitude adopted by Dr. Aldrin and his peers that people in the UK and other countries feel freely able to refer to the exploration of space as a collective human endeavor.

The 40th anniversary of the first Moon landing by humans is being shadowed in Britain with the launch of no less than two further consultations by the BNSC on the possibilities for growth in the space sector in this country and the “funding and management of UK civil space activities”. The latter consultation is effectively a request for views across the stakeholder and general public spectrum on the value of a dedicated space agency. British ventures in space, with certain exceptions like as the failed Beagle 2 Mars landing, have focused less on prestige projects and more on those with a more tangible prospect for economic gain. Indeed, the governmental agency UK Trade and Investment last year reported that the space sector is growing at 10% per year, contributing £7 billion (US$11.5 billion) per year to the economy and a massive GDP return per employee—something the government has hopefully not missed in these difficult economic times. Intriguingly it claims that “the UK’s march to success began with a decision in the 1970s not to invest in the two areas then widely perceived to define the space sector—launch vehicles and manned space flight. Since then the UK has achieved leadership in several of the most important civil sectors, including meteorology, telecommunications, and navigation.”

Perhaps the current consultation, with a dedicated consortium, the Space Innovation and Growth Team (IGT), in contrast to another recent public consultation by the BNSC, is more ambitious in that as well as attempting to identify future market opportunities and raise public awareness of space in the UK its aim is “aligning the UK’s civil, defence and security policies in science, manufacturing, and ‘downstream’ applications businesses”. However, the remit seems to focus on building upon existing strengths and investment, skills, and job creation in already revenue-generating areas or areas with potential commercial value. This rationale is sound and no doubt to be applauded but it may be a very cautious approach.

Already in New Mexico work has started on Spaceport America for the purposes of space tourism driven by companies including—but not limited to—Virgin Galactic. The same company has in the past expressed interest in developing similar ports at two sites in mainland Britain with low population density. This has yet to initiate a growing public interest in the home country of Virgin’s founder and chief source of interest in near-term future commercial space ventures (including space hotels and hypersonic travel), Richard Branson. One factor may be the reported lack of a developed regulatory structure for such ventures such as the Commercial Space Launch Amendments Act of 2004 in the US.

| It is surely the privilege of those in power, such as the minister for science and innovation, to instigate the changes during their relatively brief tenure to facilitate the germination of a sector, infrastructure, or capability base that will leave a legacy beyond their time. |

The debate on whether the UK should have a space agency has now started as a result of the launch of BNSC’s consultation. The merits of this discussion are arguably many, including whether it should be a ministry, honoring the lofty ambitions of earlier British governments and being able to take into account the full political situation at the highest level; or whether it should be an agency like NASA, which until now has been the world’s preeminent space organization. However, it is questionable whether a debate on establishing an agency (whose form would have to be decided before work began on the logistics of it) is the declaration of intent that a country led by men capable of decisive action with the widest interests in mind would take. While UK Trade and Investment makes claims to be successful on the basis of aversion to launch vehicles, and powerful politicians of the day keep space low key or at best keep launching consultations, interest in domestic capabilities and ability to direct space activities is evidenced through societies and the commercial sector. This is particularly seen in the ongoing work of companies such as Virgin Galactic, Starchaser, and Reaction Engines, as well as the British Interplanetary Society (BIS). The latter recently paid ceremonial tribute to UK-born astronauts (see “The past and future of British human spaceflight”, The Space Review, July 13, 2009) and re-launched their famous Project Daedalus interstellar probe design collaboration. Indeed, the BIS states that Daedalus “remains one of the most complete studies of an interstellar vehicle ever performed”.

It is surely the privilege of those in power, such as the minister for science and innovation, to instigate the changes during their relatively brief tenure to facilitate the germination of a sector, infrastructure, or capability base that will leave a legacy beyond their time. Certain immediate, rational actions could be taken rather than waiting for the conclusions of a labyrinthine analysis from an important but electoral-cycle crossing consultation. These could include an examination of existing regulatory legislation such as the Outer Space Act (1986) that could ease the start-up of any company wishing to invest in commercial sector reusable launch platforms that are set to become increasingly valuable to the economy. Alternatively, with President Kennedy’s inspirational rhetoric in mind, simply committing to a national goal of enabling permanent access to space from the UK within five years is not unrealistic when Richard Branson is currently on target for a suborbital flight within two years from Spaceport America.

A key factor in catalyzing public interest as NASA and astronauts such as Buzz Aldrin realized during Apollo is to promote a sense of ownership amongst the wider population in space activities. The X PRIZE Foundation, which awarded $10 million to Burt Rutan for his suborbital craft, realizes the benefits of this too, in stimulating the interest of the private sector in ways targeted to “bring about radical breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity”. Their key sponsor is British Telecom, which seems to perfectly underline importance of this initiative’s ethos to the UK: catalyze the efforts of private individuals in areas where the government is not active and chronically uninterested.

| It is the crucible that mankind is in at this moment: whether our leaders decide to drag us forward in ways that unite or let fate decide whether future generations are in a position to assume those great responsibilities. |

The overriding factor, however, is the human benefit and the human interest that ultimately crosses national boundaries. This is not an argument for or against those boundaries but for those space sector players who aspire to be “leaders” (as British representatives routinely do) to more fully pull their weight (or punch above it) and be more proactive in bringing about the changes that will take humanity into space. This is the state of tension that mankind faces as it lies between the forces of inertia, the temptation to indulge in less constructive activities, and the necessity to find something that unites us all.

Space exploration is at best not exclusive and UK governments over the past 10 years or so have begun to recognize this with opening of a National Space Centre in 2001 and a Space Academy in 2008. The latter aims to increase interest and awareness among schoolchildren in space and the possibility of space sector careers. The prospect of more schoolgirls and schoolboys taking paths to enter the space sector should be of interest to everyone from equal opportunities campaigners, educators, industry representatives, and enthusiasts witnessing the fruits of these ventures. The juncture as we arrive at the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11’s incredible accomplishment represents one of critical long-term decisions regarding aspirations and capabilities, to be made by facilitators at the highest level of power in the world’s most powerful and richest countries. It is the crucible that mankind is in at this moment: whether our leaders decide to drag us forward in ways that unite or let fate decide whether future generations are in a position to assume those great responsibilities.