Tyrannosaurs flying F-14s!by Dwayne Day

|

| The space program owes its origins to science fiction. But science fiction has also produced some of the most silly ideas for spaceflight. |

This is a scene that has been repeated throughout the history of human spaceflight, when somebody has come up with some concept for a rocket, spacecraft, whatever, that they decide can be made infinitely cooler by combining it with another concept for a rocket, spacecraft, whatever. Want to explore the icy moons of Jupiter? Let’s combine the most powerful ion engines ever built and the largest space nuclear reactor ever built and the largest rocket ever built. That would be cool. (It will also cost twenty-three billion dollars and never be built.)

Lots of people have commented about the link between science fiction and the space program. The space program owes its origins to science fiction. But science fiction has also produced some of the most silly ideas for spaceflight, ideas that sometimes persist for decades despite no clear method for achieving them or good justification for even trying (see: space solar power).

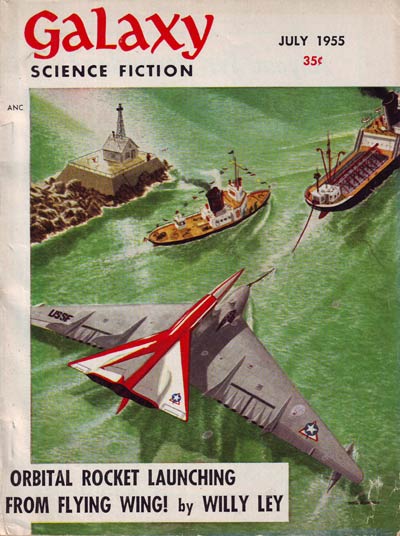

I encountered this once again when perusing the pulp magazine section of a used bookstore recently. Although I have no real interest in 1950s-era science fiction, I do like some of the old pulp cover art and recently one caught my eye. It was the cover of the July 1955 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine. It’s a painting, by illustrator Mel Hunter, of a giant flying wing seaplane being towed out to sea with a rocketplane on its back. The headline on the cover says “Orbital Rocket Launching From Flying Wing!”

Now one might assume that this was an illustration for a short story except for the fact that the cover says that this article is by Willy Ley, the famed space and science writer of the 1950s. (See “The Sputnik singularity”, The Space Review, October 20, 2008) Ley wrote non-fiction, so obviously this was non-fiction. Right?

At first glance, this cool concept appears to have a few problems. The flying wing seaplane (labeled “USSF” probably referring to the “United States Space Force”) was not the most practical launch platform. Jet seaplanes (this one has twelve—count ‘em—twelve jets) had a number of problems, including the potential to ingest seawater into the intakes and stall the engines. Although seaplanes can theoretically have an infinite takeoff space, the seas are rarely glassy smooth and water produces much more friction than landing gear. So getting this monster off the water might have been a challenge.

The magazine was only $5, so I bought it with the intention of framing it for my office. Before I did that, I opened it up to read the Willy Ley article, curious to see what Ley had to say about launching an orbital rocket from a flying wing seaplane.

Ley’s article is titled “The Orbital (unmanned) Satellite Vehicle,” and it is part of his regular “For Your Information” column that ran for many years in Galaxy. Ley described Mel Hunter’s cover illustration as “a rather startling idea, combining some elements one would not normally combine that way.”

| Ley started by discussing the history of the idea of a satellite, and noted that the idea of a robotic satellite was actually a rather recent one—for several decades all discussions of spaceflight involved putting a man in a rocketship. |

It is a pretty straightforward article, no doubt inspired by the substantial public discussion in spring 1955 about launching a robotic spacecraft into orbit. For instance, in February 1955, the journal Jet Propulsion published the proposal “On the Utility of an Artificial Unmanned Earth Satellite.” That report was produced by the American Rocket Society’s Space Flight Committee and proposed to the National Science Foundation in November 1954. Ley got a little lucky because his article, undoubtedly written several months earlier, appeared in Galaxy’s July issue that showed up on newsstands only shortly before the White House’s July 29, 1955 announcement of the start of the “Scientific Satellite Program”, which became the Vanguard program. In other words, his subject was topical.

The article is actually rather remarkable in its own right. Ley started by discussing the history of the idea of a satellite, and noted that the idea of a robotic satellite was actually a rather recent one—for several decades all discussions of spaceflight involved putting a man in a rocketship. As Ley noted, once the United States started shooting off high-altitude rockets, it began putting instruments in their nosecones and even jettisoning their nosecones. But it took awhile before anybody started to discuss putting an instrumented nosecone into orbit to become a satellite.

Now this is where it helps to know your space history. Ley was obviously unaware of the secret studies started by Project RAND, later the RAND Corporation, of “world-circling spaceships,” as RAND first called them. The first such study was in 1946, and more continued into the 1950s. So instrumented satellites were studied almost as soon as the United States started launching instrumented rockets. But Ley then discussed some of the things that an instrumented satellite could do. An instrumented satellite, for instance, could measure the temperatures encountered in sunlight and darkness while circling the Earth. It could also measure cosmic rays. This information would be valuable to designing a human spacecraft.

But where Ley’s article started to really get interesting was when he turned to the subject of an uninstrumented satellite, which he suggested could be as simple as a bale of hay. The primary benefit was that it would be cheaper. Ley argued that such a satellite could still be useful. The most obvious task for it would be determining atmospheric density. Put one satellite at 180 miles, another at 250 miles, and another at 300 miles, he wrote, and you could monitor how much it slowed down in its orbit and determine how much atmosphere was dragging on it.

Because it was possible to learn something from an uninstrumented satellite, Ley suggested that the first satellite launched, or even the first two or three, did not require instrumentation. He even suggested that the satellite could be an inflated balloon, or even a ball of foam, like a “shaving cream bomb.”

Once again this is where it is useful to know your space history. Of course the Soviet Union launched an uninstrumented satellite (Sputnik’s radio beacon doesn’t count as an “instrument”). And of course they beat the United States to orbit. Today lots of people mistakenly believe that the United States government “allowed” the Soviets to launch first in order to establish the right to overfly foreign territory while in orbit so that the U.S. could eventually fly its spysats over the rest of the world. Although establishing “freedom of space” was indeed American policy, it was not why the United States lost the space race. The reason was that the United States explicitly rejected the concept of a simple satellite with only bare instrumentation, (or none at all), in favor of a satellite that would accomplish significant science.

You can see this approach repeated again and again throughout the space age: the Soviet Union sought to use a simpler spacecraft to achieve an engineering first—i.e. a stunt—whereas the United States chose to design more complex spacecraft to return greater data. The mold was cast with Project Vanguard.

| But Ley’s article, touted as “orbital rocket launching from flying wing!” on the cover, contained no flying wing. |

What Ley was arguing, only a few weeks before the United States officially declared its scientific satellite policy, was that the simple approach had merit. If, in mid-1955, your interest was science, you probably were not convinced by Ley’s argument. However, if you were interested in seeing spaceflight accomplished at all, or if you were concerned about the Soviet Union possibly getting there first, you probably agreed with Ley.

Ley also discussed the possibility of air-launching the satellite. Haul it up beneath a high-altitude balloon and then shoot it off. Or use a jet.

But Ley’s article, touted as “orbital rocket launching from flying wing!” on the cover, contained no flying wing. And no seaplane. When Ley wrote that the illustration depicted “a rather startling idea, combining some elements one would not normally combine that way,” he was being generous. He was avoiding saying that the entire concept was crazy.

Of course, this was just a clever bit of space art intended to sell the magazine, which was probably successful. After all, it convinced me to buy it.

Now if only that flying wing was piloted by a tyrannosaur…