|

|

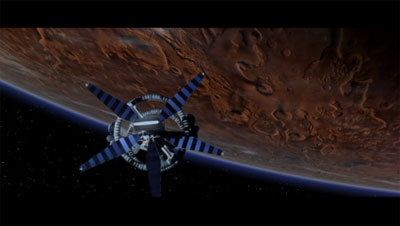

Red Planet was not a cinematic masterpiece, but it was the better of the two Mars-themed films released in 2000. (all photos credit: Warner Home Video) |

Planet Hollywood, part 2: Red Planet

<< page 1: they all go to Mars

Mission to Mars’ production designers sought to accurately portray the surface of Mars. But they clearly took some liberties. The Mars in that movie is hyperreal, with lots of canyons and cliffs and mountains, all computer generated. Red Planet’s designers also used some computerized imagery, but they apparently relied more on actual geology, filming many of the scenes in deserts in Jordan and Australia. Although the differences are subtle, Red Planet’s depiction of the Martian surface is more appealing, in part because it simply seems more real. Mission to Mars put geological features into the scenes because they looked good, but they were still manufactured. For the most part, Red Planet used topography and geology that really exists. Although sometimes they exaggerated.

|

Both movies got the sky wrong, however. In Red Planet the sky is either pink or light red. Mission to Mars shows it as a deeper red/orange. In reality, the Martian sky is a butterscotch color, which is less appealing than the movie versions.

| Mission to Mars put geological features into the scenes because they looked good, but they were still manufactured. For the most part, Red Planet used topography and geology that really exists. |

Eventually the three survivors near the Russian spacecraft as night approaches. They hide in a cave to protect themselves from the cold. But Burchenal has been needling Pettengill about what happened to Santen back on the cliff. He doesn’t believe Pettengill’s claim that Santen jumped off the cliff rather than suffocate. Pettengill decides to flee and ride the Russian spacecraft himself, although how he plans to do this is never quite explained considering that he has to fix it first.

Burchenal and Gallagher go after Pettengill only to discover that AMEE has apparently reached him first. He’s dead and as they struggle to remove his remaining oxygen to use on the ascent into orbit, they discover something else, life on Mars in the form of millions of small nematodes. The organisms ate all the algae and also produced a lot of oxygen. They pop like firecrackers.

Burchenal is surrounded and attacked by them. He captures one in a specimen tube and tosses it to Gallagher, then sets himself afire, going up like a bomb from all the oxygen-laden nematodes that have overtaken him. The explosion is so massive that it is visible from orbit.

Gallagher then heads to the stranded Russian craft. Fortunately, he just happens to be the one person knowledgeable to fix it. Also fortunately, the craft comes with a handy little access port and display screen that allows him to access the vehicle’s software, which is reprogrammed with new orders sent from Earth and relayed through Mars One.

But just as he prepares to start the countdown, the spacecraft’s battery dies. Gallagher figures that this is the end. There’s no way that he can get off the surface unless he can power the spacecraft’s guidance system. He collapses, figuring that AMEE is going to show up and kill him soon anyway.

Of course this doesn’t happen. Of course he comes up with a plan. He realizes that AMEE’s helium nuclear fuel cell can power the spacecraft. So he develops a trap for the robot, rigging the spacecraft so that when AMEE approaches he can fire the spacecraft’s parachute, which knocks over the robot and traps it. He manages to pull the robot’s fuel cell free as it self destructs.

The clock is ticking. Gallagher hops into the now empty sample return hold. He says “[Expletive] this planet!” and launches the spacecraft. It starts to disintegrate as he rises up to orbit.

By amazing coincidence, he happens to fly up right nearby the orbiting Mars One. He suffers cardiac arrest and Bowman performs an EVA and drags him and the spacecraft into Mars One, where she revives him.

Later, as a denouement, we see the nematode that he brought with him and Bowman says that it may prove able to rescue the polluted Earth, because Earth’s problem is apparently decreasing oxygen levels, not, er, pollution.

There are some minor, but extraneous aspects to the plot that could have easily been chopped. For some reason we’re told early on that Bowman does not like Gallagher. But later it develops that the two are attracted to each other and have been in denial, leading to one of the film’s resolutions when they are ultimately reunited and kiss. It’s a rather odd contrivance, probably meant to give us a reason to hope that Gallagher does eventually make it back to the ship, as if simply not dying was insufficient. It’s also somewhat quaint—they’re too adults, on a dangerous space mission, and the big question is if they’re actually going to kiss, as if this is a John Hughes film.

Kilmer, for his part, does a lot with some rather limited dialogue. When he’s stuck with the malfunctioning Russian spacecraft, apparently doomed, he manages to convey a certain exhausted sadness, tinged with fatalistic humor as he talks to Bowman in orbit. “Well, that’s about it…” he says, tired. “I really hate this planet… I really miss Earth. I really miss a lot of things.”

Dueling Mars

Set aside all the contrivances, such as Gallagher’s ability to hotwire a Russian spacecraft using a nuclear battery never intended for that purpose, or his ability to fly up in the vehicle and make it close enough to Mars One to be rescued. Of course the movie has some plot holes and some problems with technical and scientific accuracy. The lander would not look like it does, for instance, and if there was a breathable atmosphere on Mars the crew would have been able to tell from orbit—in fact, the atmosphere would have been visible from Earth—and it would not have been a surprise. But Phil Plait, of the Bad Astronomy website, notes that some of the film is scientifically and technically accurate, sometimes cleverly so. Plait gives the movie kudos for some of this, and overall has positive things to say about the film.

| From a storytelling standpoint, Red Planet is the better film. |

January thru March has typically been a dumping ground: the time when Hollywood studios premiere movies that they originally had high hopes for but ultimately concluded were doomed. Not surprisingly, that’s where they dumped Mission to Mars, which premiered in March 2000. That said, the film grossed $60 million domestically, nearly double the $33 million earned by Red Planet, which premiered in the much more marketable month of November. Mission to Mars had a budget estimated to be $75–100 million. Red Planet reportedly had a budget of around $80 million. It’s nearly impossible to accurately factor in all the other costs (advertising, theater fees) and revenue sources (DVD sales, syndication), but Red Planet bombed, and probably lost the studio money, whereas Mission to Mars also lost money, but may have eventually broken even.

But it is not box office that determines how good a film is (witness Transformers 2). The two films are rated equally by reviewers on Amazon.com, although Red Planet pulls slightly ahead of Mission to Mars for fan votes on the Internet Movie Data Base. From a storytelling standpoint, Red Planet is the better film. Although it throws a succession of crises at the heroes throughout the story—solar flare, crash landing, destroyed hab, potential suffocation, killer robot, killer bugs, killer robot again, and countdown clock—the movie does follow a more traditional storytelling arc, building to an exciting climax. In contrast, the only “excitement” in Mission to Mars comes in the middle of the film, with a long, dull, and badly-executed sequence involving depressurization, and engine explosion, and then an emergency EVA (you know you’re in trouble when a movie resorts to showing a pressure gauge for tension). All of this is accompanied by a sleep-inducing musical score. The climax of Mission to Mars, if you can call it that, is a planetarium show where the characters all stare in awe at a green screen. Red Planet at least blows up a killer robot.

Red Planet trouces Mission to Mars in the musical score department. Whereas Mission to Mars had a soporific instrumental soundtrack apparently produced on a Casio keyboard by once-great composer Ennio Morricone, Red Planet had music by Sting, the Police, Peter Gabriel, Emma Shapplin, and composer Graeme Revell. Both Shapplin and Revell’s compositions are pretty good, especially when played alone. They have a lot of emotion packed into them. But in the DVD version of the film they’re not well used, mostly hiding in the background, overtaken by the dialogue and the sound effects.

Visually, although Mission to Mars is more accurate, having borrowed many of its hardware designs from Robert Zubrin and NASA’s Mars Design Reference Mission, Red Planet looks cooler. The spaceship interior doesn’t make a lot of sense (none of the corridors curve, despite the centrifuges), but the spacesuit designs and other hardware look better.

However, whereas Red Planet’s hardware does not rate high for accuracy, the movie’s science is not bad. It remains one of the few movies that have even mentioned the concept of terraforming, let alone made it a major plot point. Red Planet takes the concept and gives it a twist, however, saying that the future of humanity may not reside on Mars, but can be saved by what comes from Mars. Gallagher’s shouted insult aside, Mars may be Earth’s best hope.

| Red Planet remains one of the few movies that have even mentioned the concept of terraforming, let alone made it a major plot point. |

Perhaps the biggest disappointment for Red Planet is that it could have been a better film with only a little bit of extra effort. Delete the irrelevant romance subplot, cut down on some of the walking-across-Mars scenes, and pick up the pace, and it would be more exciting. Emphasize a few of the friendlier relationships, like Gallagher and Chantilas, and even Burchenal and the other crewmembers (Tom Sizemore may be a personal wreck, but the guy has charm) and the film would have had greater appeal.

It’s too bad that Terrence Stamp collected his check and departed the film early, because his character provided a bit of spirituality that the film could have used. Red Planet’s philosophical message seemed mostly tagged onto the film. If the director had emphasized it more, it would have lifted the entire film. It was a message that maybe science alone is insufficient to explain the universe.

Dwayne Day realizes that he needs to read good books, not watch mediocre movies. But he still believes Red Planet is not a bad film. He can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

|

|