A tipping point for commercial crew?by Jeff Foust

|

| The next few months may be critical in determining not just which companies are serious about developing crewed systems, but how much support, in the form of policies and funding, they can expect from the federal government. |

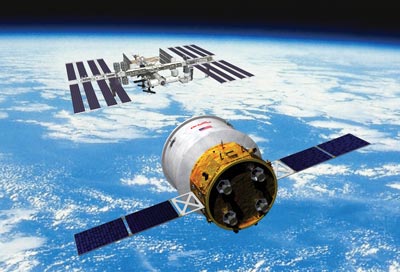

The development of such systems faces a number of major technical and financial hurdles, which is why some in the industry have argued for NASA to support their development—especially since NASA could be a major user of such systems to access the International Space Station (ISS) once the shuttle is retired. Such support, they argued, would be not only a natural outgrowth of NASA’s existing Commercial Orbital Transportation Service (COTS) program, but would be necessary for such systems to be truly commercial and not locked into only carrying cargo to the ISS (see “The COTS conundrum”, The Space Review, July 28, 2008).

COTS as originally structured did include an option for crew transportation—the so-called “Capability D”—but only one company, SpaceX, appeared to be actively interested in it: Orbital Sciences Corporation, the other company with a funded COTS award, was focused only on cargo transportation to the station. Could commercial crew transportation be that commercial if there was only one company out there?

However, interest in commercial crew transportation appears to be growing. Enticed by a modest amount of NASA funding—and perhaps a bigger shift in the policy winds—several major companies are now actively proposing commercial systems for carrying humans into orbit. The next few months may be critical in determining not just which companies are serious about developing crewed systems, but how much support, in the form of policies and funding, they can expect from the federal government.

Crystallizing policy

One of the biggest developments in recent weeks is an apparent about-face by Orbital. Previously the company had been focused only on cargo delivery to the ISS—its plans did not even include returning cargo to Earth (“Capability C” in COTS parlance), let alone crew transportation. Company officials previously said they didn’t see enough of a market in crew transportation to justify the expense involved in developing a crew-capable version of its Cygnus spacecraft.

That thinking has changed. Space News reported two weeks ago that Orbital had proposed a crewed version of Cygnus capable of carrying three or four people, launched atop a human-rated version of its Taurus 2 rocket. A company spokesman said that the upgraded spacecraft and launch vehicle could be developed for $2–3 billion.

Asked about this development during a keynote session at the AIAA Space 2009 conference in Pasadena on September 15, Orbital CEO Dave Thompson acknowledged the report, but said little more about it. “Like others, we have been exploring the mid-term prospects for commercial human spaceflight, at least to and from the International Space Station,” he said, defining “mid-term” as four to five years after program start.

“We have to be careful here that we not let expectations run out too far in advance of near-term reality,” he added. “But we are looking are ways that we could develop, over time, a suitably safe and reliable means of providing limited functionality for a relatively small number of astronauts to and from the ISS.” He said that “small” in this context meant three or four people, as previously reported by Space News.

In a panel about the COTS and CRS programs later that day at the conference, Orbital vice president Bob Richards provided additional context about the company’s reasons for studying a crewed version of Cygnus. “As the nation seems to be crystallizing some of their policy in the direction of commercial crew systems, it appears to us now that it’s more realistic and more of a national priority,” he said. If that’s the direction NASA wants to go, he said, “we definitely want to be a part of it.”

| “As the nation seems to be crystallizing some of their policy in the direction of commercial crew systems, it appears to us now that it’s more realistic and more of a national priority,” Richards said. |

While not explicitly stating it, Richards appeared to be referring to the summary report of the Review of US Human Space Flight Plans Committee (aka the Augustine committee after its chairman, Norm Augustine) released earlier this month. Six of the eight options included in that report—all but the current “program of record” in either the current or a less constrained budget—make use of commercial options to transport cargo and crew to the ISS.

“Commercial services to deliver crew to low-Earth orbit are within reach,” the report’s concluding section reads. “While this presents some risk, it could provide an earlier capability at lower initial and lifecycle costs than government could achieve.”

Even before the Augustine committee’s report came out, NASA was embarking on a limited effort to kickstart development of commercial crew capabilities with $50 million of the $1 billion in stimulus funds appropriated to the agency earlier this year. The Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program is designed to, in the agency’s words, “foster entrepreneurial activity leading to job growth in engineering, analysis, design, and research, and to economic growth as capabilities for new markets are created.” The funding is far short of what’s needed to actually develop such systems, but could begin work on key technologies needed to enable them.

Proposals for the CCDev program were due to NASA last week, and it’s widely believed Orbital, SpaceX, and others submitted proposals. In an interesting twist, Boeing issued a press release last week that it has submitted a CCDev proposal, teaming with Bigelow Aerospace, the Las Vegas-based company developing commercial orbital habitats—and thus another customer for any commercial crew transportation system. Boeing also joined three other teams submitting CCDev proposals.

“Boeing has a lot to offer NASA in this new field of commercial crew transportation services,” Keith Reiley, the Boeing program manager for its CCDev proposal, said in the statement. “To show our commitment, we are willing to make a substantial investment in research and development.”

Boeing didn’t release technical details about its proposal, but it’s likely to use launch vehicles from United Launch Alliance (ULA), the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture that produces the Atlas and Delta launch vehicles. ULA has been promoting those vehicles as options for launching crewed vehicles, either for commercial vehicles or, during the Augustine committee’s deliberations this summer, as an alternative to Ares 1 for launch Orion. The ULA booth in the Space 2009 exhibit hall, for example, had several models of the Atlas 5 with different vehicles on top, from a generic capsule to the Dream Chaser lifting body design proposed by Sierra Nevada Corporation (formerly SpaceDev).

| “I believe that manned spaceflight is something that is still in the realm of government, because despite their best efforts, some truly private enterprises have not yet been able to deliver on plans of launching vehicles,” Sen. Shelby said in May. |

SpaceX hasn’t been sitting still while other companies are showing renewed interest in commercial crew transportation. At Space 2009 company president Gwynne Shotwell said that the company was “exploring the possibility” of putting a demonstration model of the Dragon spacecraft—designed ultimately to be able to support crew as well as cargo—on its inaugural Falcon 9 launch, before the company carries out the three Dragon missions that is part of its COTS agreement with NASA. The company confirmed those plans in an update posted on its web site last week.

“Bet the farm” on commercial space?

While commercial crew transportation is gaining interest from a number of companies, it faces obstacles that go beyond technology and business models. Any effort by the White House and NASA to give commercial providers an opportunity to support or even supplant government vehicles for carrying astronauts into low Earth orbit is likely to meet with some Congressional opposition, based on recent hearings.

In May, Sen. Richard Shelby voiced his concerns about NASA relying on commercial providers and spending money on them versus the Constellation program. “I believe that manned spaceflight is something that is still in the realm of government, because despite their best efforts, some truly private enterprises have not yet been able to deliver on plans of launching vehicles,” he said in opening testimony of a hearing of the appropriations subcommittee with oversight of NASA, singling out SpaceX in particular. “However grandiose the claims of proponents” of commercial crew transportation, he added, “they cannot substitute for the painful truth of failed performance at present.”

Shelby’s opposition to commercial crew held up the release of NASA’s stimulus funding for several weeks, according to various reports. Eventually that money was released, but the $80 million originally planned for CCDev was reduced to $50 million.

In the House Science and Technology Committee’s hearing September 15th about the Augustine committee report, Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who chairs the committee’s space subcommittee, expressed similar concerns. “Nor do we gain by confusing hypothetical commercial capabilities that might someday exist with what we can actually count on today to meet our nation’s needs,” she said in her opening statement, which was critical in general of the Augustine report. She wondered why the committee had not examined the case of “fully funding Constellation, where is that going to take us, not that someday the commercial space sector is going to step in and be able to create something that they have yet to be able to create.”

She picked up that thread later in the hearing when questioning two additional witnesses, Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel chairman Joe Dyer and former NASA administrator Mike Griffin. She asked them if it was wise of the country to “bet the farm” on commercial providers for transportation to the ISS.

Griffin, who initiated the COTS program shortly after becoming administrator in 2005, made it clear in his response to Giffords that while he believed that commercial alternatives would eventually be an option, it was not something that the country should rely on in the near term.

“To use your words, ‘betting the farm’ on commercial space transportation is unwise,” he said. “I am one who believes that, as with airplanes and air transport, there will be a day when the US government, as one option, can turn to commercial providers. But that day is not yet and it is not soon.”

He added: “To confuse the expectation that one day commercial transport of crew will be there… with the assumption with its existence today or in the near term, I think is risky in the extreme.”

Any proposal to use commercial alternatives to the current Constellation architecture will also face opposition from ATK, the company developing the first stage of the Ares 1. Company officials have expressed skepticism that commercial providers can perform commercial crew transportation any faster, or any safer, than what is planned under Constellation.

| “I am one who believes that, as with airplanes and air transport, there will be a day when the US government, as one option, can turn to commercial providers,” said Griffin. “But that day is not yet and it is not soon.” |

An example of this is an op-ed that appeared in Sunday’s issue of the Washington Times by Michael Bloomfield, a former astronaut who is now a vice president at ATK. “Though commercial vehicles with a launch abort system may be safer than the shuttle, they still lag behind Ares I safety by a factor of 3 to 5 and do not meet the Columbia investigation’s clear assertion that America should replace the shuttle with a vehicle that is ‘significantly safer,’” he stated. “Asking start-up companies working to deliver cargo to the International Space Station to take on the task of safely delivering crew to low-Earth orbit is fraught with multiple unknowns, risking significantly increased costs, both monetarily and in human life.”

The challenge facing companies proposing commercial crew transportation systems, and their advocates, is demonstrate that their systems can be safer, less expensive, and available sooner than any government system, particularly to skeptics on Capitol Hill who could hamstring any commercial crew transportation effort through appropriations or authorization bill language.

“I don’t believe that we can be responsible stewards of the taxpayers’ dollars if we let hope and ideology trump the evidence,” Rep. Giffords said in the House hearing earlier this month. Convincing such skeptics may prove to be as significant a challenge as any technological or financial obstacles commercial crew transportation providers might face.