Is Ares 1 too little, too late?by Edward Ellegood

|

| As Dr. Griffin might point out, big aerospace programs are no strangers to cost overruns, technical problems, and schedule delays. It seems to me, however, that the problems with Ares 1 are more fundamental. |

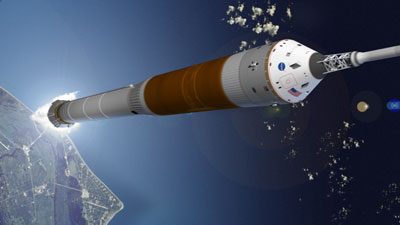

Originally envisioned as a simple and low-cost reuse of Space Shuttle hardware, Ares 1 has become increasingly complex and expensive while its scheduled availability slides farther and farther to the right. Adding to Ares 1’s complexity and cost are challenges with the upper-stage “common bulkhead” and the J-2X engine, which have been cited by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in a recent report as adding significant risk to the program. Efforts to mitigate these and other risk factors have contributed to the Aerospace Corporation’s finding that we shouldn’t expect an operational Ares 1 until 2017, five years beyond the 2012 target originally put forward by NASA in 2005.

As Dr. Griffin might point out, big aerospace programs are no strangers to cost overruns, technical problems, and schedule delays. It seems to me, however, that the problems with Ares 1 are more fundamental. According to the GAO report released on September 25, the development costs for Ares 1 and its Orion crew capsule are likely to reach $49 billion, nearly double the $28 billion originally proposed. That’s billion with a “B” for a limited-mission rocket whose lift capacity is similar to already-developed Atlas and Delta rockets—vehicles that could be human-rated and ready sooner than Ares 1 and at a lower cost, according to the Aerospace Corporation study.

While Dr. Griffin and others may be able to argue that Ares 1 costs are on track, and provide reasons against relying solely on commercial rockets for crew flights, it is harder to deny that Ares 1 is becoming a too-little/too-late solution as scenarios for Constellation and the International Space Station (ISS) evolve. The Augustine committee’s eight human space exploration options, as presented in their Summary Report to the White House, bear this out.

Specifically, Ares 1 and the International Space Station (ISS) do not operationally or fiscally coexist in any of the options presented in the Summary Report, rendering the vehicle useless for ISS crew carriage. In other words, the Augustine Panel believes NASA can fund Ares 1 or the ISS, but not both.

| I believe Ares 1 has become a solution in search of a problem and a symbol of the government’s role as a gatekeeper for space. |

Furthermore, with its limited performance, the operational Ares 1 would be all dressed up with nowhere to go, waiting several more years for a heavy-lift partner to enable exploration missions beyond low Earth orbit. This “heavy-lift gap” is my biggest problem with Ares 1. The Augustine committee correctly asserts that a heavy-lift rocket is required for any meaningful exploration program, whether to the Moon, Mars, or other destinations. However, by sticking with Ares 1, NASA would actually prolong that gap until the mid- to late-2020s.

So, although I too am concerned about changing rockets mid-flight, I believe Ares 1 has become a solution in search of a problem and a symbol of the government’s role as a gatekeeper for space. Unless the Augustine committee’s conclusions change significantly in their final report, it seems NASA should focus its efforts on developing a heavy-lift vehicle and give the private sector more responsibility for servicing the ISS.