Instruments of God’s creationby Dwayne Day

|

| Every field has its holy relics, the objects that are held in such high regard by those who practice in that field, or admire the field, that they are imbued with almost holy significance. Space is like that. |

The objects are the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2—more commonly referred to by its acronym WFPC2, pronounced “wifpic”—and the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement, with its simpler acronym, COSTAR. Both are highly sophisticated optical instruments that flew aboard the Hubble Space Telescope. Both were removed from Hubble during the famous space telescope’s recent, and last, servicing mission this past summer. Both were placed on display in the museum in the past few weeks.

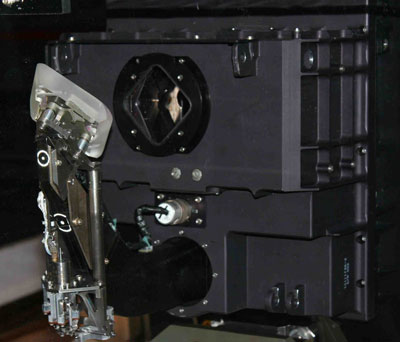

The WFPC2 instrument on display at the National Air and Space Museum. (credit: D. Day) |

WFPC2 is on display in one of the main exhibit areas of the museum, only a few meters away from the museum’s engineering mockup of the Hubble telescope. WFPC2 is probably the easier of the instruments to understand. It’s a camera, the one that took the Hubble’s most famous photos (so far), such as the 1995 image of the “pillars of creation” that captured the imaginations of so many people around the world. When you look at the instrument, which is about the size of a large kitchen table, its basic operation is apparent. It is shaped somewhat like a pie slice, so that it can slide into the middle of the cylindrical telescope. At its front is a small angled mirror that bends the light coming down through the telescope 90 degrees into the camera itself. Nearby photographs depict the camera being removed from the telescope when it was replaced by the WFPC3.

Many of the images NASA released from WFPC2 had an odd, serrated shape. This came from a unique feature of the camera. WFPC2 actually consists of four cameras that took four images, like four frames of a window pane. But one camera was higher resolution. Scientists then processed that single frame and reduced it, so that the overall image from the four cameras had a jagged shape.

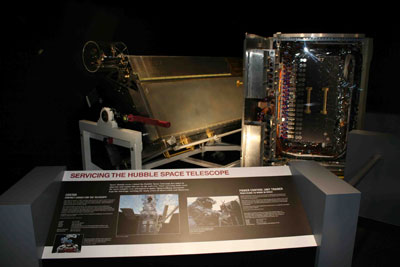

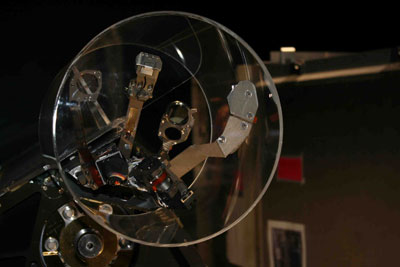

COSTAR on display at the National Air and Space Museum. (credit: D. Day) |

The other instrument on display, COSTAR, in some ways is more famous. COSTAR was the instrument that saved Hubble’s reputation, and made all of the other scientific discoveries possible.

COSTAR is in a newly opened exhibit in the museum called Moving Beyond Earth. The theme of the exhibit is “human spaceflight since the 1970s—people traveling to space, living and working there, and seeking to move beyond Earth.” It is meant to cover subjects such as the Space Shuttle, International Space Station, Russia’s Mir space station, and plans for future flights beyond low Earth orbit.

In many ways the exhibit is the museum’s initial effort to address the looming challenge of dealing with the retirement of the Space Shuttle, which will result in NASA retiring and disposing of millions of objects from the program, such as hundreds of flown laptop computers and many tools used by astronauts during various projects such as the Hubble servicing missions and space station assembly.

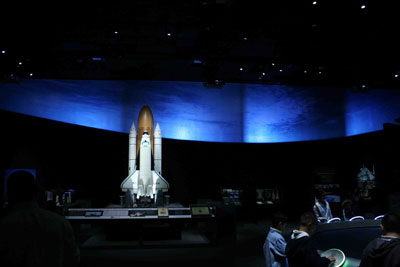

The new “Moving Beyond Earth” gallery at the National Air and Space Museum. (credit: D. Day) |

Right now the exhibit has an unfinished, rather schizophrenic feel. Most of the artifacts on display were previously displayed next door in the space race exhibit and have only been moved. These include the museum’s impressive model of a space shuttle on its launch pad, astronaut flight suits, a Russian space toilet, and models of the Soviet Buran space shuttle. There is no connective text linking them together, and the primary linkage is that they all date from the 1970s or later.

One of the objects on display is COSTAR. When Hubble was launched in 1990, it carried a powerful mirror that was ground perfectly wrong, a phenomenon known as spherical aberration. This is actually rather common for large telescopes, and so camera manufacturers test for it and then correct the optics to compensate for the problem. But the Hubble manufacturer disregarded test results that showed the problem and NASA did not assert proper quality control over its contractor, and so Hubble reached orbit with a flaw that rendered it next to useless.

| Some have expressed disappointment that Hubble itself will never be placed on display in the museum. But Hubble belongs out there. |

In 1993 NASA launched the first of its Hubble servicing missions and astronauts installed COSTAR. COSTAR was not really an instrument itself—it did not take any measurements of its own. Instead, it was a set of corrective lenses that fixed the images going to the other instruments, such as WFPC2, already aboard the telescope. COSTAR is mostly a big box, and the business end is a tiny set of arms that fold out in one corner, each containing a small optical device for fixing the image and bouncing it to an instrument. As with so many museum artifacts, context is everything, and so the text provided with the display is vital for many visitors to understand what they are looking at. After COSTAR, all new instruments installed in Hubble had their own corrective optics and COSTAR was no longer needed.

Both WFPC2 and COSTAR still belong to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, located just outside of Washington itself. Goddard has its own small museum. But the center’s leaders understand that the National Air and Space Museum is one of the most visited museums in the world and the proper place to display their icons. Soon WFPC2 and COSTAR will be joined by other famed relics from the space telescope.

Some have expressed disappointment that Hubble itself will never be placed on display in the museum. But Hubble belongs out there, among its fellow stars.