A comic book, the Cold War, and the Moonby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Hergé wanted to anticipate the future and it was obvious after the war and the development of the V-2 rocket that a trip to the Moon was going to happen sometime within the next few decades. |

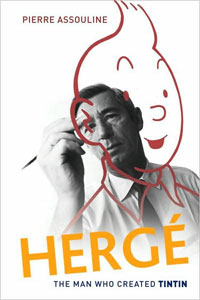

The Tintin books were the key to creating a large and highly profitable publishing industry in Europe, especially in Belgium, that specializes in what is called “La Bande Desssine”. This is a comic book culture very different from the American one, which is often symbolized by the Comic Book Guy character in The Simpsons. While some of it is most emphatically “adult”, the original Tintin stories were almost painfully innocent and moralistic. Why they were so is part of what makes Pierre Assouline’s 1996 biography of Tintin’s creator (recently published in English) so interesting. “Hergé” was the pen name of Georges Remi: he simply reversed his initials to RG, pronounced “Hergé”.

Born in 1907 near Brussels, he grew up in a world of strong Catholic middle class values best expressed by his participation in a church-sponsored Boy Scout group. When he finished High School his talents as an artist lead to him being hired by the Vingtième Siècle, an ultramontane newspaper run by the Abbé Norbert Wallez. The paper soon began to print a weekly special for children called Le Peitit Vingtième. It was in this supplement that the character Tintin first appeared in 1930.

Hergé spent most of the Second World War working comfortably for a collaborationist newspaper. After the war he avoided any consequences of this due to the authorities belief that they would look ridiculous prosecuting a popular children’s cartoonist. Yet many of his friends were purged and his resentment never went away. Like many Europeans, he had always detested both American capitalism and Soviet communism. He was however, smart enough to stay away from direct political commentary.

According to his biographer he wanted to anticipate the future and it was obvious after the war and the development of the V-2 rocket that a trip to the Moon was going to happen sometime within the next few decades. One can speculate that in 1944 and 1945 Hergé saw the contrails of the German rockets.

A trip to the Moon fit in with the Tintin plot format. The adventures would almost always take place somewhere far away from Belgium, such as South America or the Balkans. The Moon was the ultimate exotic destination.

| In Europe the baby boomers expected, thanks to Tintin, that the first expedition to the Moon would be an international one. Instead they saw their own nations stand on the sidelines while the US and the USSR engaged in an epic struggle. |

The story involves the mysterious disappearance of Professor Tournesol (Professor Calculus in the English version) who sends a telegram asking his friends to join him in the Balkan nation of Syldavia. There, a large-scale secret international science center has been established to build an atomic powered rocket that will make the trip to the Moon and back again. This is purely a “humanitarian” operation: no question of building atomic bombs, and, in the book, no mention of putting such weapons on top of rockets. Hergé and his team researched the book within the limits available to them in the early fifties. The drawings of the atomic pile used to process the fuel for the atomic rocket engine were particularly well done.

The drawings of the Moon itself were based in part on Chesley Bonestell’s pictures from Willy Ley’s book The Conquest of Space and from the famous Collier’s magazine illustrations. According to Assouline, one of Hergé’s assistants went to the best source available: NASA, which of course did not exist in 1953. Other details, particularly regarding weightlessness were accurate, obviously the result of expert advice.

A subplot involves spies working for an unidentified foreign power, that may or may not be the Soviet Union or the US. In any case they are trying to steal the secrets of Tournesol’s rocket engine. Again, this is a natural part of the Tintin format.

What made this story important was not just Tintin’s dramatic first words as he steps out onto the Moon’s surface, but the way that this comic book shaped the expectations of a generation. In Europe the baby boomers expected, thanks to Tintin, that the first expedition to the Moon would be an international one. Instead they saw their own nations stand on the sidelines while the US and the USSR engaged in an epic struggle.

Historians may someday determine that the impetus for the creation of the European Space Agency (ESA) was more than just the need to pool national resources in a single entity. It may have, at least in part, been due to the vision of a Belgian comic book artist who sent a boy and his dog to walk on the Moon.