Review: My Dream of Starsby Jeff Foust

|

| The title of the book comes from her childhood in Iran, where she described looking up in the night sky as both a “playground for my mind” as well as “a refuge… away from all the sadness in my life”. |

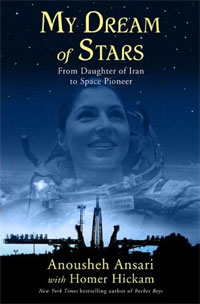

Those seven people attracted varying degrees of public and media interest, but among the more highly-publicized journeys was that of Anousheh Ansari. The first (and to date only) female space tourist, the Iranian-born American entrepreneur had already attracted attention as the title sponsor of the $10-million Ansari X PRIZE, designed to promote suborbital space tourism. With the assistance of noted writer Homer Hickam, she tells the story of that flight to the ISS and the events that led up to it, in My Dream of Stars, the second book in recent months from a commercial visitor to the ISS (see “Review: By Any Means Necessary”, The Space Review, January 4, 2010.)

The title of the book comes from her childhood in Iran, where she described looking up in the night sky as both a “playground for my mind” as well as “a refuge… away from all the sadness in my life”. That sadness came from family problems, including the divorce of her parents, and later the upheaval caused by the Iranian revolution in the late 1970s. Eventually she and other members of her family left Iran, settling in the United States, where she quickly learned to adapt and thrive.

For much of the 1990s that “dream of stars” was deferred as she, with her husband and brother-in-law, built up a technology business they later sold for $750 million. With that wealth she considered her options to realize that dream, only to find that companies promoting such flights “were mostly just fluff and moonbeams.” However, she was more receptive to a pitch by the X PRIZE Foundation, who needed money to cover the “hole-in-one” insurance needed for the prize purse. They eventually became the title sponsor for the competition, won in 2004 by Scaled Composites.

That, however, was not enough to satisfy her dreams of space flight. About a year later, Eric Anderson of Space Adventures offered her the opportunity to train in Russia as the backup to the company’s latest client, a Japanese entrepreneur named Daisuke “Dice-K” Enomoto. She agreed, and went through the months of medical tests and training in Star City without knowing when—or even if—she would be able to fly. To her surprise, that opportunity came almost immediately: Enomoto was medically disqualified (due to kidney stones, according to later accounts) and as the backup she took his seat, with only a few weeks to prepare for a journey of a lifetime.

| There is value in telling the story of her experience in space, and the effort to realize that nearly life-long dream. Ansari tells that story skillfully, and at times almost poetically, in this book. |

For many readers, the account of her flight will be familiar because she blogged about her flight; excerpts from the blog, as well as a selection of comments—both positive and negative—are included in the book. (One interesting item: according to Ansari, NASA got to “review and censor” the blog posts she emailed to the ground through NASA’s system, although the only thing they changed were brand names, which were replaced with more generic terms: “candy” instead of “M&Ms”). Still she shares the whole experience, from the wonders of weightlessness and seeing the Earth from the space to the bout of spacesickness she suffered from early on her trip. She also recounts a series of “friendly arguments” she had on the station with ESA astronaut Thomas Reiter, who was skeptical of private sector involvement in space. “In his opinion,” she writes, “to send people into space just for the experience was of no value.”

Many readers of the book will likely think otherwise. Certainly, there is value in telling the story of her experience in space, and the effort to realize that nearly life-long dream. Ansari tells that story skillfully, and at times almost poetically, in this book. Hickam, best known for his coming-of-age memoir Rocket Boys, no doubt helped craft that story, but other than a two-page discussion of the different approaches of NASA and its Russian counterpart to private human spaceflight, he remains behind the scenes.

If there is one letdown in My Dream of Stars, it’s in the follow-through. Only a four-page epilogue covers what happened after she returned from her flight. In the book she mentions several times her goal of developing private spaceflight (even telling the astronauts she’s leaving the station with at the end of their mission to contact her when they retire if they’re interested in piloting private vehicles), but there’s no mention of that in the epilogue, and no public developments of late. (Her new company, Prodea Systems, intends to “address the challenges of today’s increasingly complex digital home and connected small business environment”, according to its web site.) Was her dream of spaceflight satisfied with a single journey in space? From the passion conveyed in the book, that seems unlikely.