A spacefaring hydraulic civilizationby Taylor Dinerman

|

| On or off Earth, the way any society distributes and uses water determines its ultimate destiny. |

Now that scientists have found huge deposits of water ice on the Moon, the question arises of who will control these “hydraulic resources” and under what authority? Wittfogel thought that in societies like China, ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Russia, there emerged a “class in a society whose leaders are the holders of despotic state power and not private owners and entrepreneurs” and that “in hydraulic society there exists a bureaucratic landlordism, a bureaucratic capitalism, and a bureaucratic gentry.” His vocabulary may seem a bit archaic in 2010, but the danger he described is all too real.

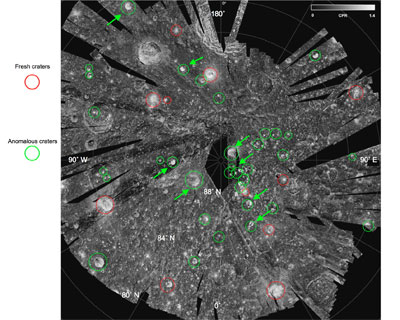

The size of the water find on the Moon, estimated at 600 million metric tons in the Moon’s north polar region alone, may seem like a lot, but it is roughly the equivalent of the annual output of six mid-sized desalinization plants. Because of its location it may end up being very valuable indeed. It is also an indication that water may be common throughout the solar system.

On or off Earth, the way any society distributes and uses water determines its ultimate destiny. This is obvious not only to any farmer or rancher, but to anyone living in or near a flood zone, or to any politician looking at what happened to George W. Bush’s presidency after Hurricane Katarina. Under normal circumstances people in the developed world expect to turn on the tap and have clean water come out. They seldom think about the amazingly complex system responsible for that result.

In space, water is even more precious than on Earth. Onboard the International Space Station (ISS) the efforts made to recycle every molecule of moisture are well known. Yet water is still going to be one of the most important items to be delivered to the station by the various cargo carrying vehicles built by Russia, Europe, Japan, and by NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation System. Since the ISS partnership is well established and runs fairly smoothly, there have been no significant disagreements over the use of these water resources.

Once the water on the Moon or Mars or the asteroids becomes accessible to humanity, the ownership and control of it will determine which nations or peoples will truly be able to profit from space resources. The unratified Moon Treaty may have its fans, but once the value of the Moon’s water becomes evident, particularly the possibility of using it to produce liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen for rocket fuel, it will become just another irrelevant scrap of paper. Peacefully or otherwise, the major spacefaring powers will come to an agreement giving “squatters rights” to whoever first occupies and claims a given bit of the icy Moon.

| There are plenty of institutions, and people who run them, who would be all too happy to take control of the solar system’s water resources. One can be certain that they will claim to be doing so with the best of motives. |

The challenges involved in mining the deep craters of the lunar poles are gigantic. Yet on Earth we see that huge deep-sea oil drilling platforms are able to search for oil kilometers under the seabed. As long as the prize is of sufficient value there is no reason to think that human ingenuity will be diminished any time soon. Yet it the very size of this challenge that may lead to a kind of interplanetary hydraulic despotism. If the organization and technology needed to extract water from the Moon and from other celestial bodies is even more complex and expensive (on a relative basis) than that used to irrigate and regulate the great river valleys of China, then the prospect for the future of liberal capitalism in the solar system may be pretty dim.

If, however, the technology is fairly compact and easy to use, then a whole new tribe of ice-seeking entrepreneurs and partnerships will spring up and go to work. For this to happen, a safe legal environment will have to be in place to allow them secure property rights over what they find. This means that the US, as the world’s leading liberal democracy, will have to find a way to be present on the Moon or someplace else where there are large accessible supplies of water, and set a legal precedent.

There are plenty of institutions, and people who run them, who would be all too happy to take control of the solar system’s water resources. One can be certain that they will claim to be doing so with the best of motives. Yet, as Wittfogel pointed out, “the hydraulic state prevents the nongovernmental forces of society from crystallizing into independent bodies strong enough to counterbalance and control the political machine.”

If, in the course of humanity’s expansion into the solar system, such a controlling authority were to be installed, it would freeze any hope for a spacefaring civilization made up of free and independent men and women. The control of water would lead to the control of other vital space-based resources. In time the institution’s power would grow until it would be able to have a stranglehold on the flow of off-Earth resources down to the surface of this planet.

For many, in America and elsewhere, this is not a happy thought.