Bigelow still thinks bigby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’ve been talking to prospective clients for two years now, and we have yet to ask anybody for money,” Bigelow said. “We don’t intend to ask anybody for money until perhaps 2012.” |

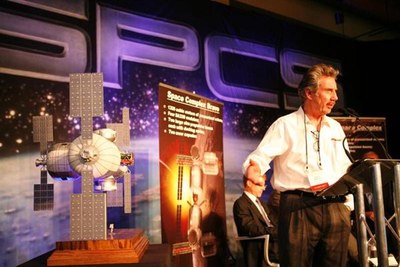

That, though, is only the tip of the iceberg for the relatively-secretive company. At the International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight (ISPCS) in Las Cruces, New Mexico, last month, Bigelow Aerospace had an exhibit that demonstrated how large their ambitions truly are. On display was a model of “Space Complex Alpha”, its baseline space station, which uses one BA 330 module (so named because each has 330 cubic meters of volume) and two smaller Sundancer modules, linked together with a docking node a propulsion bus. The company was also showing off a larger concept, Space Complex Bravo, which uses four BA330 modules with two docking nodes and two propulsion buses.

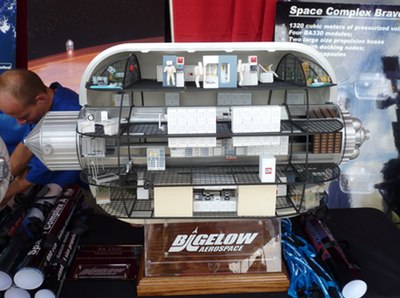

Even that, though, was modest compared to other concepts on display at the booth. Besides models of the Sundancer and BA330 modules, the company showed off a concept called the BA2100. As the name suggests, this module would have 2,100 cubic meters of habitable volume, over six times that of the BA330. The cutaway model on display showed four decks arranged lengthwise inside the module, providing plenty of room for crew quarters and lab space within the same module. Posters on display in the booth showed various applications for the BA2100, in conjunction with the BA330 and other components, from a resupply depot dubbed Hercules to a “Biological Containment Station” in LEO that could be boosted out of orbit if necessary.

Bigelow Aerospace officials staffing the booth confirmed that the BA2100 was a new concept, and the exhibit at ISPCS was the first time the company was publicly showing off the module concept. The company disclosed few other details about the module concept, beyond the fact that it would be too large to be launched on any existing rocket: they would need a heavy-lifter of some kind with a payload fairing of seven to eight meters.

Despite these bold plans, the company itself was still relatively modest, Robert Bigelow said during a session of the ISPCS. “We’re a small company: our staff totals between 110 and 115 people,” he said. SpaceX, by comparison, now has about 1,000 employees. “We still qualify as a small business.”

In the relatively near term, though, the company is still focused on building the Sundancer and BA330 modules that will form the basis of its initial space stations. While the company has often been portrayed as a developer of “space hotels” for space tourism, Bigelow has maintained for years that their primary markets are for research and “sovereign clients”, national governments interested in leasing a space station but without the means of developing their own (see “Big plans, low prices”, The Space Review, April 16, 2007). Just prior to the ISPCS, the company revealed that it has signed memoranda of understanding with six countries—Australia, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—interested in using Bigelow’s facilities. Those are the beginning of as many as 50 countries that Robert Bigelow believes would be interested in using those habitats.

Bigelow admitted, though, that the recession has made it more challenging to make deals “Because of the recession, and because of other things, we’ve been conscious of the shallow depth of the pocketbooks” of potential customers, he said at ISPCS. As a result, they’ve expanded the “menu” of options for potential customers from seven or eight to eighteen, adjusting the amount of time and volume on the stations that clients can lease.

Bigelow is also holding off on collecting money from potential customers. “We’ve been talking to prospective clients for two years now, and we have yet to ask anybody for money,” he said. “We don’t intend to ask anybody for money until perhaps 2012.”

A model of the Bigelow Aerospace BA2100 module that would offer over six times the volume of its planned BA330. (credit: J. Foust) |

“Occupied with transportation”

A bigger challenge for the company—and one of the key reasons they’re not in a rush to collect money, even deposits, from their customers—is finding the means to access the habitats once launched. Once even the simplest habitat is assembled, it will need a steady stream of spacecraft launched to it, carrying crews and cargo needed to maintain and utilize the facility. That’s a big obstacle for the company since, at the present time, there are effectively no commercial options for this beyond Russia’s Soyuz and Progress spacecraft.

That has made Bigelow into a big fan of NASA’s efforts to develop commercial crew transportation systems designed to service the ISS, but which also could be used to access Bigelow facilities. “We’re very interested in what happens to CCDev, to say the least,” he said, referring to the shorthand name of NASA’s Commercial Crew Development program.

| “If anything keeps us awake at night, it’s not just transportation—that’s number one for us—and number two is the lack of launch facilities,” Bigelow said. |

Bigelow, though, has been focused on the problem long before CCDev. In late 2004 Bigelow established America’s Space Prize, a $50-million award for a commercially-developed crew transportation system. That prize expired in January with no teams making a serious effort to win it; the prize rules that prevented teams from accepting government development funding effectively ruled out the only company that appeared to have a reasonable shot at the prize, SpaceX. “We have been occupied with transportation since the inception of our company,” he said. “It’s just that we can’t fight a two-front war, so we try to concentrate on creating a safe, reliable, affordable destinations.”

At ISPCS, Bigelow revealed that he had been working with Lockheed Martin on a capsule concept in the 2004–2005 period. “We engaged in a million-dollar contract a couple years after that with Lockheed, and they created for us an Orion mockup, an Orion Lite.” (Ironically, Bigelow said later in the ISPCS session on commercial crew transportation that he was not a fan of the full-scale Orion, calling it “redundant”: getting crews to LEO could be handed by commercial vehicles, he said, while larger vehicles—such as expandable modules being developed by Bigelow Aerospace—should be used for deep space exploration.)

More recently, Bigelow has partnered with Boeing on the development of the CST-100 crew spacecraft, which Boeing has been working on with a small CCDev award this year. “We are very excited about Boeing’s effort,” he said, but added he was also still interested in SpaceX and the development of its Dragon spacecraft: “We cheer them on as well.”

What Bigelow offers Boeing, SpaceX, and other vehicle developers is the promise of a sustained, large market for space transportation services. Bigelow said that with the initial Alpha station Bigelow would need six flights a year; with the launch of a second, larger station, that number would grow to 24, or two a month.

“We will be a substantial consumer of rockets and capsules and all kinds of hardware for these things,” he said. He anticipates being such a major consumer he’s worried about the ability of existing launch sites to support it, and is looking at alterative, underutilized sites like Wallops. “If anything keeps us awake at night, it’s not just transportation—that’s number one for us—and number two is the lack of launch facilities.”

Keeping a long-term schedule

Bigelow’s big plans for human spaceflight aren’t limited to low Earth orbit: the company had on display in its exhibit concepts for deep space, including Mars, exploration. “We do have lunar ambitions,” Bigelow said, adding that he hoped to bring together clients for LEO operations into “coalitions” for lunar bases. “We also see the Moon as a jumping-off point for Mars.”

Bigelow himself has been taking on a higher profile in addition to his appearance at ISPCS, where he spoke on two panels and spent time talking to people at the company’s exhibit, he put in a similar appearance at the AIAA Space 2010 conference, where he spoke in several sessions and simply attended a number of others.

At Space 2010 he also attended a meeting of the AIAA Commercial Space Group, informally discussing various aspects of his business, including what his schedule was like. “In 2000, somebody asked me this question, ‘When do you think you’re going to have your first space station operational?’ And I said by 2015,” he recalled. He noted that in marketing materials published by the company just this year, “in there, it says 2015 for operations.”

“I think the prospects are pretty fair that we’ll be able to service clients in 2015.”