Space solar power’s Indian connectionby Jeff Foust

|

| “The bottom line was, to get that monolithic system required a single, stupendously large project, analogous to a super-Apollo project,” Mankins said of 1970s-era SBSP designs. |

SBSP was just one of many topics discussed at the Space Manufacturing 14 conference, organized by the Space Studies Institute (SSI) and held at NASA Ames on October 30 and 31. The conference, the first of its kind held by SSI since 2001, dates back to the mid-1970s, when the promise of low-cost access to space would enable everything from solar power satellites to full-fledged space colonies. In the decades since, though, SBSP, like many other farsighted concepts discussed at the first Space Manufacturing conferences, have fallen out of favor, becoming niche topics of interest at best and fringe issues not taken seriously by the mainstream space community at worst. However, interest nearly halfway around the world from the conference site might be giving SBSP some new momentum.

Simple vs. “stupendously large”

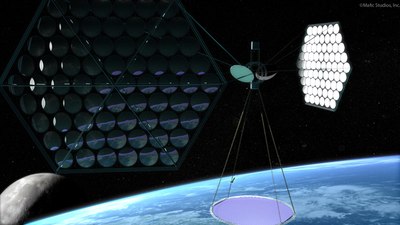

One of the biggest criticisms of SBSP has been the scale of the infrastructure needed to generate significant amounts of power. John Mankins, president of Artemis Innovation Management Solutions LLC and the leader of NASA’s “Fresh Look” studies into SBSP in the 1990s, noted that a 1979 reference study featured a structure measuring 5 by 20 kilometers, capable of generating 10,000 megawatts of power.

“The bottom line was, to get that monolithic system required a single, stupendously large project, analogous to a super-Apollo project,” he said at the SSI conference. The first working prototype of such a system would take 20 years to develop, as envisioned at the time, at a cost of $80 billion or more.

Advances in technology, though, have rendered those original concepts not just unaffordable but also obsolete. “Imagine if one were to build a supercomputer, with today’s capacity, using the technologies and the components that were available in 1970,” Mankins said. Similarly, he said, it was possible to develop SBSP systems without the need for the mega-projects proposed in the 1970s.

How much smaller? Mankins said the International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) is completing a study on SBSP, due out next spring. That study is looking at three SBSP concepts with the idea of not transmitting power to a single fixed point on the Earth, as was planned in the original 1970s concepts, but instead be able to transmit to any number of locations “in order to satisfy optimum market conditions.”

The finding of the study group—still undergoing peer review, Mankins said—is that with a new technology roadmap a pilot SBSP system could be relatively affordable. “Within 10 to 15 years, a pilot plant, delivering megawatts of power, could in fact be realizable within a finite amount of budget,” he said, with “finite” meaning $5–10 billion. “It’s not trivial—it’s a big effort—but it’s not an impossible amount of money.”

“A James Webb Space Telescope-class investment by the international community, both industry and space agencies, could in fact realize a subscale but operationally scalable multi-megawatt solar power satellite demo within 7 to 15 years,” he concluded.

| “I have been proposing that large missions, like bringing space solar power to the Earth, would need the combined efforts of nations,” Kalam said. |

For far less it may be possible to demonstrate one of the key technologies of SBSP, transmitting power from space to the Earth. Asked how much it would cost to fly a satellite that could beam a token amount of power—enough to perhaps power a single light bulb—Mankins said that a “quick and dirty demo” using off-the-shelf technology could cost $1–10 million. A more robust demonstration using technologies on the path towards larger SBSP systems would cost somewhat more: $20–50 million.

John Mankins discusses the state of SBSP research at the SSI Space Manufacturing 14 conference at NASA Ames on October 31. (credit: J. Foust) |

India’s role in SBSP

Those 1970s-era studies also assumed that the United States would be the lead, if not only, nation involved in the development of SBSP systems: a rational assumption at the time given the capabilities of other spacefaring nations. However, just as technologies have advanced during the last three decades, so have the capabilities—and energy needs—of other nations, opening up opportunities for cooperation not envisioned three decades ago.

One example formally announced at a Washington, DC, press conference on Thursday by the National Space Society is the Kalam-NSS Energy Initiative. The project is a joint venture that plans to bring together American and Indian experts to discuss technologies associated with SBSP at a bilateral meeting planned for next May in Huntsville, Alabama, in conjunction with the International Space Development Conference, the annual conference of the NSS.

What gives this effort added prominence is one of the Indian supporters of the effort: Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, the former president of India. Kalam worked on missile and space programs in India before becoming president in 2002, earning the nickname “Missile Man of India”. He promoted India’s space efforts during his five-year tenure as president and is now lending his name and interest to this new effort.

“I have been proposing that large missions, like bringing space solar power to the Earth, would need the combined efforts of nations,” Kalam said, speaking by phone from India. His interest in SBSP, he said, came from a need to meet India’s growing energy requirements while moving away from fossil fuels. “We need to graduate from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.”

While the idea of cooperation between the two countries on space solar power has been brought up in the past (see “Should India and the US cooperate on space solar power?”, The Space Review, June 8, 2009), the concept was discussed in detail more recently in an August 2010 white paper by Peter Garretson, an Air Force lieutenant colonel who had a fellowship at India’s Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses. In the paper, he outlined the concept of solar power from space and how it might serve to advance the strategic partnership between the United States and India.

In the paper, Garretson calls for a three-stage joint effort for development of an SBSP system, after an initial (“stage 0”) creation of a bilateral framework: a technology development study, development of a demonstration system, and then full-fledged production. While the final stage would cost tens of billions of dollars, Garretson wrote that the technology study stage could be done for only $10–30 million over about five years.

Why should the two countries cooperate on SBSP, though? At Thursday’s press conference, NSS CEO Mark Hopkins noted that the two countries have “so much in common”, ranging from a shared colonial history to strong public interest in space. Both also have growing energy requirements, especially in India as that populous nation modernizes, and SBSP could meet those needs and more. “India and the United States can become major net exporters of energy,” he said.

| “Basically, you’re talking about a combination of American technology and the ability of India to do a lot of low-cost manufacturing,” Hopkins said. |

It was less clear, though, at Thursday’s press conference, what exactly India could bring to the table in terms of technologies and other capabilities to enable SBSP. Asked what India could provide, Kalam spoke about the development of what he called a “hyperplane”, a reusable spaceplane that could greatly lower the costs of space access. “For solar power satellite success, we need a launch vehicle system… which can bring down the costs from $20,000 to $2,000 a kilogram,” he said.

The Indian space agency ISRO has been studying a spaceplane concept called Avatar that would use a combination of ramjet, scramjet, and rocket engines to achieve orbit, but has yet to begin flight tests of even subscale technology demonstrators. Given the difficulties India has faced with less complex launch vehicle technologies, such as cryogenic upper stages for expendable launchers (the first flight of an indigenously-developed cryogenic upper stage for its GSLV launcher failed in April of this year), as well as the technology challenges of RLV development as demonstrated by past US efforts, it suggests that the “hyperplane” may be many years in the future.

T.K. Alex, director of the ISRO Satellite Centre and the Indian leader of the Kalam-NSS Energy Initiative, said later at the press conference that India could also contribute technology in the area of high-efficiency and lightweight solar panels. Hopkins, though, suggested India’s role might be in helping keep system costs down. “Basically, you’re talking about a combination of American technology and the ability of India to do a lot of low-cost manufacturing,” he said.

The press conference took place the day before President Barack Obama left on a three-day visit to India. That trip is expected to include some announcements related to space, including the removal of ISRO from the U.S. “Entity List” for high-tech exports, a step that would remove one obstacle for American companies seeking to export some items to India. However, SBSP is not expected to be on the agenda of meetings between Obama and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Kalam suggested that it instead be brought up at a future meeting of G8 or G20 nations.

Whether these efforts—the IAA study and the Kalam-NSS initiative—give new life to SBSP remains to be seen. Space solar power has been largely out of the mainstream of discussion in both the space and energy fields for decades (see “Blinded by the light”, The Space Review, June 7, 2010), and official support—and funding—for such work has been in short supply. Comebacks, though, are always possible, if the right circumstances arise. After all, Jerry Brown was elected governor of California on Tuesday.