Fly me to the starsby Lou Friedman

|

| Neither the Department of Defense nor NASA is thinking of building a starship or conducting an interstellar flight, but the questions raised by studying such projects are relevant to current space program planning. |

The workshop organizers talked about creating a business model for a hypothetical organization to advance interstellar flight. I don’t quite understand the “business” aspect, nor do I share some of the assertions at the workshop about government space exploration being uncertain and that we should look for more private sector involvement. After all, the United States has been steadily exploring planets in the solar system for 50 years; private businesses have a long way to go to show such consistency. But I do agree with many good ideas presented of ways that government and private sector can both make advances, and how even private entrepreneurs can get involved in the technology development. After all, my own Planetary Society LightSail effort is a private sector, entrepreneurial, early step toward interstellar flight.

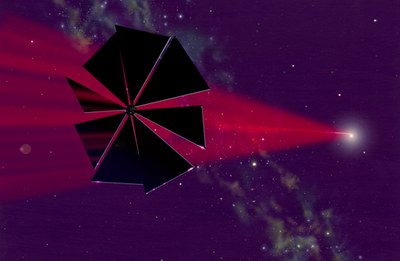

I have previously written that interstellar flight might be closer than we thought although still not imminent. Even traveling at a speed ten times that of Voyager—equivalent to going to Pluto in one year—the trip to the nearest star would be an impractical 10,000 years. For interstellar travel, the future is with lightsailing, and that would require an advanced laser or other radiation propulsion technology to provide the push needed. That is why we are still perhaps a century or more away from practical interstellar flight.

And even that is with ultra-light robotic spacecraft, with masses of less than 10 kilograms, and still able to communicate over the long distances. At the conference, almost everyone was discussing human travel. But they were also thinking of valuable near-term milestones for interstellar flight.

The first will probably be the identification of good targets: discovering promising extrasolar planets that could be habitable or even inhabited. That might happen in the next few years, and certainly within the next decade. Other milestones would mark capabilities for long-duration human exploration: creating an artificial biosphere; conducting long-duration experiments such as the Russians and Europeans are doing with the Mars-500 project, or those on the space station; sending human missions into the solar system; and settling humans on Mars.

Lightsailing development for missions that come close to the Sun and then shoot through the solar system could develop the propulsion technology, and advances in information technologies will provide further milestones.

| Space exploration always needs to answer “why?” and “where are we heading?” If we are creating the future for humans in the universe, we must occasionally look at where we are going. |

One really provocative idea using information technology was advanced by microbiologist Craig Venter: sending signals from Earth with information to create synthetic life out of constituents on a complex Earth-like planet in another star system. That would be interstellar flight at the speed of light, so long as that synthetic life could signal us about their success. It is pretty way out—but maybe less so than sending actual humans on the voyage.

The milestones mentioned make this subject relevant. Space exploration always needs to answer “why?” and “where are we heading?” If we are creating the future for humans in the universe, we must occasionally look at where we are going. It is not the time to advocate that NASA (or any other government agency) begin working on an interstellar program. After all, we still can’t get intelligent government planning for where to send humans just beyond the Moon. But we can engage the public and stimulate our scientific and technical communities by forming some non-governmental initiatives. We already have interested groups: the British Interplanetary Society, Tau Zero Foundation, the SETI Institute, the 10,000 Year Clock and Long Now Foundation, and, of course, The Planetary Society, all represented at the workshop. Former astronaut Mae Jemison emphasized the need to also involve and motivate young people with interesting goals and projects. Her science education organization, and others, should also be involved in any follow-up.

I hope this visionary thinking continues. Pete Worden, the NASA Ames director, and Dave Neyland, director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office, deserve credit for creating the workshop. Getting Peter Diamandis, the entrepreneur and creator of innovative organizations, to lead the discussion helped to advance new ideas. It was an intelligent antidote to stale thinking that often emanates from Washington. Looking to the stars has long been the source of inspiration for the advancement of knowledge and new achievements of humankind.