The case for international cooperation in space explorationby Lou Friedman

|

| International cooperation is enabling a golden era of robotic space exploration even in the face of budget cuts and increasing costs. |

The interdependency of national space programs will play a part in the big space exploration decision that Europe has to make later this year: what to explore in the 2020s. Because of the complications of having over a dozen nations involved in decision-making and project implementation, the European Space Agency has to make decisions long in advance of their technical necessity. They will probably decide this year or next on their next big step in space exploration and choose a mission that will probably not launch until well into the 2020s.

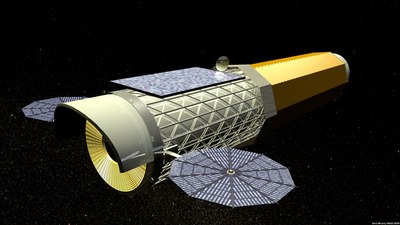

They are considering their first outer planets mission: an orbiter of Jupiter and its giant moon Ganymede, to fly as a companion to NASA’s putative Europa orbiter. An International X-Ray Observatory is also being considered in cooperation with both NASA and JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. It would be a large telescope companion to the James Webb Space Telescope at the Sun-Earth Lagrangian point, L2. The third candidate in the science competition is a gravity wave detector called LISA, Laser Interferometer Space Antenna. It would be a cooperative mission with NASA, utilizing three satellites.

The decision on which of these three large-class science missions to develop could come in the middle of this year. NASA and JAXA decisions will clearly affect European decision-making, and vice versa. I am concerned that the lack of funding in the president’s proposed budget for an outer planet flagship mission, expected to be a Europa orbiter, might lead ESA to give up on its Ganymede companion. But perhaps it will have the opposite effect, since it could be re-cast as an independent mission and allow Europe to take over from the US as the main outer planets explorer in the 2020s. LISA and IXO are more interdependent international missions, and LISA in particular will be affected by the proposed cuts in US space science. IXO could be done solely with Japan, but Japan is having its own space science budget problems and might be influenced by the cuts in other countries. The European Union is having its own furious debate about debt and budgets, and ESA budget cuts to their existing program are possible despite the fact that their planning tends to be more stable because of the long lead times.

For several years ESA has been developing a highly ambitious ExoMars astrobiology mission for Mars exploration. It was so ambitious that they had to step back and make it part of a cooperative plan with NASA, beginning with a 2016 entry, descent, and landing technology test vehicle that would fly as companion to the US Mars Trace Gas Orbiter. That latter mission was included in the President’s budget, but the follow-on cooperative NASA lander to fly in conjunction with ExoMars was not. How will that affect ESA planning?

In their budget rollout last week, NASA officials described how they have given up on a US dark energy astrophysics mission, and instead will focus on cooperating with the Europeans’ nascent Euclid mission. Euclid is one of three so-called medium class science missions competing for final selection this year to launch near the end of the current decade. The others are an exoplanet detection mission called PLATO and a solar orbiter to study the Sun. Two will be selected (we hope).

| The world needs a positive, inspiring, outward-looking venture that can engage skilled personnel around the world in developing new technology. Let’s back off from the national-only planning and start planning internationally. |

In short, international cooperation is enabling a golden era of robotic space exploration even in the face of budget cuts and increasing costs. It’s a touchy situation because interdependency not only builds up new capabilities but can, because of the dependency, undermine the planning. And the current focus on budget cutting in all countries could undermine everything, stopping space exploration just as Spain, Portugal, and Holland stopped ocean exploration centuries ago.

However, given the fact that globalization already dominates exploration of the solar system and observation of the universe, and that the International Space Station has now merged the human space flight programs of spacefaring nations, why don’t we strengthen human exploration planning with an international approach? Strengthening is badly needed. How much of a leap is it to combine robotic Mars landers with International Space Station missions to produce a program that takes humans into the solar system?

In my view it is time for the political leaders (not just the space agency heads) to get together on a new human space initiative. It is clear that the US and Russia are not going to do it alone despite the assertions by space enthusiasts in both countries that they can. Europe and Japan have shown themselves to be strong players with meaningful contributions. China and India are standing on the threshold.

As I have said many times, space agency folks alone can’t make it happen: only a geopolitical purpose will drive support for a major human space mission. The world needs a positive, inspiring, outward-looking venture that can engage skilled personnel around the world in developing new technology. Let’s back off from the national-only planning and start planning internationally. Budget realities, if nothing else, demand it. Maybe Europe, which has overcome many of the nationalistic inhibitions to cooperation, should step up and be a leader in making it happen.