Inflatable POOFsby Taylor Dinerman

|

| The radiation protection characteristics of inflatable modules has attracted the attention of the NASA space architect and the people designing the missions that will take us back to the Moon and beyond. |

The combination of the ability to expand and the ability to protect against radiation is giving inflatables their essential role in the new exploration vision. Boeing’s pictures of its CEV concept prominently includes inflatables for in space uses as well as for surface habitats. Inflatables were also part of the now defunct L-1 Gateway idea.

So far, these concepts are just old-fashioned “viewgraph engineering.” To find something closer to reality, one must look outside the traditional government/contractor nexus. Bigelow Aerospace, based in Las Vegas, picked up the TransHab technology after NASA abandoned it. Aside from a few press releases, Bigelow kept a low profile and put a lot of time and money into turning NASA’s technology into something that may actually make commercial sense.

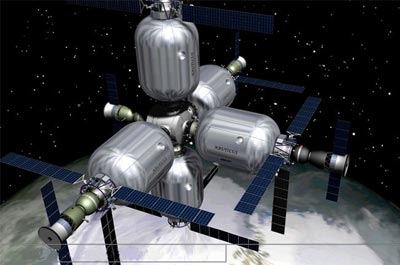

In any case, the refined version of TransHab that has recently been written up in Aviation Week seems to have real potential as a multipurpose habitable space structure that will complement, or compete with, those that are currently being made in Russia and Italy. Called Nautilus, these modules could be the 40-foot containers of the space industry. With a standard Russian-origin docking system, they could be assembled into a manned space facility in low Earth orbit for both privately- and publicly-funded research and for space tourism. Even better, they could be used as the basis for a CEV fueling station in LEO, or even in orbit around the Moon.

The best news of all is that Bigelow is planning to test a subscale version in November of next year. He plans to fly it on the first of SpaceX’s Falcon 5 rockets. He plans a second test flight using the Russian Dnepr rockets. Together, these will give Bigelow a good chance to prove out his technology years before Boeing or Lockheed Martin get their chance to fly comparable technology.

One sign that NASA has changed is that, instead of giving Bigelow the cold shoulder, they are encouraging him and his company to continue this work. It would be logical for NASA to make plans to include NASA sensors on the test flights. This would give them detailed data on system performance, particularly for radiation shielding. Once assured that the Nautilus modules conform to basic requirement, the US space agency can plan a whole series of spacecraft built around them.

| One sign that NASA has changed is that, instead of giving Bigelow the cold shoulder, they are encouraging him and his company to continue this work. |

Bigelow’s project for a private space habitat using his module, combined with Russian hardware (and, judging from the image they released, an Italian-built node) looks plausible. An effective space station will need far more solar arrays than are in the picture and probably will also need larger heat radiators. The basic idea of a private space station, serviced by Soyuz and Progress vehicles, is well within the state of the art. Where this gets tricky is figuring out how economically viable such a project would be.

A research facility that would take up some, if not all, of the science that cannot be done on the ISS, will probably not be a major source of cash flow. The science work on the ISS was never a priority. While the US and its partners would be happy to have a facility that would take over some of the work, they probably would never be willing to pay the full costs of putting such experiments into a privately owned orbital facility (a POOF?) At best, Bigelow could expect to recover 70% or 80% of the expenses.

This would be no problem if NASA were willing to subsidize the POOF as a transfer and assembly point for lunar missions and beyond. Depending on what architecture is chosen for the return to the Moon project, a station in equatorial orbit would be a useful place to assemble vehicles that will travel from Earth orbit either to lunar orbit or directly to the lunar surface. Indeed, such a station might spare NASA the expense of having to develop and build a new class of super heavy, Saturn 5-type rockets.

Bigelow also seems to have had some discussions with China. While these are surely useful in terms of establishing the beginnings of a relationship between the US and Chinese space industries, experience dealing with China indicates that there is plenty of room for caution. In the future, the US and PRC will certainly cooperate in space but, for now, the relationship will be limited.

The US is extremely lucky that Robert Bigelow picked up the inflatable ball that NASA dropped. If things go well, a Bigelow owned and built POOF will be a major transportation hub for people traveling to the Moon, or elsewhere, in cislunar space—kind of like an intelligently-located hotel.