Review: Fifty Years on the Space Frontierby Jeff Foust

|

| A theme of Farquhar’s career is one of innovation and also independent thinking, both in spacecraft design and when dealing with bureaucracies. “Throughout my career, I have resisted excessive management control,” he writes in the book’s preface. |

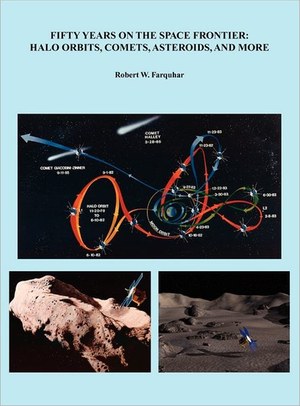

As Farquhar recounts, he first became aware of Lagrange points as a student at the University of Illinois in the late 1950s; fascinated with the concept, he ended up getting his Ph.D. on the subject of placing satellites at Lagrange points at Stanford University a decade later. “At this time I had one obsessive and overriding ambition—that was to design and implement the first mission to a libration point,” he writes. After discussing with NASA a concept to place a communications satellite at the Earth-Moon L2 point in order to support a proposed (but never flown) Apollo mission to the lunar farside, he got his wish in the 1970s when he convinced NASA to fly a space physics mission, the International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3) spacecraft, in a halo orbit around the Earth-Sun L1 point.

Farquhar’s penchant for innovation went beyond placing a spacecraft at a Lagrange point, though. After NASA plans to mount a mission to Halley’s Comet fell through, Farquhar and colleagues found a way to send ISEE-3 from its L1 halo orbit to another comet, Giacobini-Zinner. The spacecraft, rechristened the International Cometary Explorer (ICE), flew past that comet in September 1985, beating out the international flotilla of missions headed to Comet Halley by six months. Later, he served as mission director for the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) spacecraft, which went into orbit and eventually landed on the asteroid Eros, and also worked on the MESSENGER mission to Mercury and the New Horizons mission to Pluto.

A theme of Farquhar’s career is one of innovation and also independent thinking, both in spacecraft design and when dealing with bureaucracies. “Throughout my career, I have resisted excessive management control,” he writes in the book’s preface, an assessment supported throughout the book by events where he went above manager’s heads or simply did his own thing in support of a particular mission. Sometimes this was to win support for a particular mission or event, such as pushing for a flyby of another asteroid by NEAR en route to Eros even though the project scientist and project manager were opposed. Other times it was for more personal, even idiosyncratic reasons, such as designing NEAR’s revised trajectory (after a engine problem nearly ended the mission en route to Eros) so that the spacecraft could enter orbit around the asteroid on February 14, 2000—Valentine’s Day.

| He’s also pushing to give new life to the ICE spacecraft, asking NASA to fund a new extended mission for the spacecraft that would use its 2014 Earth flyby to put the spacecraft on course for a 2018 flyby of comet Wirtanen. |

That inclination for independent thinking extends to the book. He admits in the preface that the book could have been improved by a professional editor, but that “better is the enemy of good enough.” And yes, an editor might have been able to tighten up the text and perhaps rework some of the more technical elements of the book. Fifty Years on the Space Frontier is, though, more of a professional memoir than a personal one: he spends little time discussing his personal life in the book, putting much of it, including his childhood and marriages, into the book’s prologue. One interesting aspect of the book is the inclusion of an appendix with a number of key documents from his career, featuring a variety of memos, letters, and emails associated with events he recounts in the book.

Farquhar, who turned 79 earlier this month, is still active in spaceflight, working for an aerospace engineering company, KinetX, while developing the latest version of a “Cosmic Study” for the International Academy of Astronautics on human spaceflight, building upon earlier work that bears some similarities to the “Flexible Path” approach later adopted by NASA (see “The L2 alternative”, The Space Review, December 4, 2006). He’s also pushing to give new life to the ICE spacecraft, which remains functioning more than 30 years after launch. Noting that ICE’s orbit brings it back to the vicinity of the Earth in 2014, he’s asking NASA to fund a new extended mission for the spacecraft, using the Earth flyby to put the spacecraft on course for a 2018 flyby of comet Wirtanen. He admits there are many obstacles to winning support for the extended mission and the $25 million needed to pay for it, but Farquhar is undaunted. “I have until 2014 to persuade NASA to do this mission, and I will not give up easily,” he writes. If anyone doubts that, they need only read his book.