Knocking on Heaven’s Doorby Dwayne A. Day

|

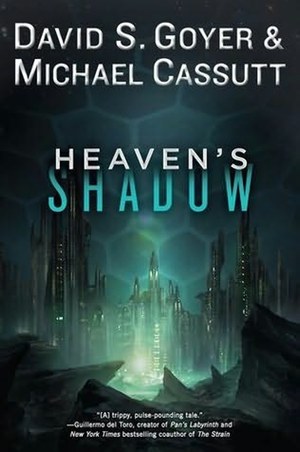

| It’s actually about an unusual type of First Contact, humans encountering an alien vehicle and an alien intelligence. |

David and I had met through a mutual friend, producer Michael Engelberg, in 1994, and stayed in touch. In 2004 he read an SF screenplay of mine that he liked and talked about trying to set up—nothing happened then, but a couple of years later, he invited me to lunch to pitch two projects to me, one of which was this near-future encounter with a NEO. He knew my SF background would be helpful, of course, but he really wanted my perspective on NASA, astronauts, and spacecraft.

Did you start with an idea that excited you both, or did you decide to work together and then worked on the idea?

The core idea in Heaven’s Shadow was David's. We started working on a long, detailed treatment for a movie in January 2007—during the first few weeks, we turned the concept into a trilogy (figuring that in success, the movie would have a sequel or two), then decided to try the trilogy as a series of books, too.

So you already have Heaven’s Shadow as a movie treatment, and now you’re writing the books. Are you guys gluttons for punishment or is writing a book fun?

Writing a book is a lot more time-consuming than writing a screenplay. On the other hand, generally you write a book once. Screenplays can go through multiple revisions. Ultimately the workload seems about the same.

Except that in this case you’re doing both! How much of the story do you already have mapped out in your heads? Do you know exactly where it is going, or do you have a general idea and you let the writing take you there? Or do you have absolutely no clue?

We have a clue. As I said, long before we finished the first storyline, we had notes for the second and the third. We know where it ends, even though the writing may yet give us some surprises.

When you start writing, you have a general idea where the story is going, but do things suddenly come up, like you realize that you need an extra character, or more background or detail, and the story starts taking you in another direction?

I have a note or a line or an event in mind when I sit down to do, say, the day’s work. In the case of a novel, which takes months, and proceeds best when worked on every day, I find that I wake up thinking or re-thinking yesterday’s pages or today’s upcoming scenes.

I start writing, and will often find that a line occurs to me that doesn’t fit here. I’ll put it later in the scene and write to it, or delete it when I get there. Or put it somewhere else, once I’ve gotten deeper into the moment.

Yes, you realize you need a character to come onstage and do something. You look around, grab one of your other cast members, and give them a line or an action. Sometimes you need a fact or bit of background. You get it, and realize you’ve either screwed yourself or, more happily, opened up a new bit of action. Stories can take off in a new direction, but I’ve never let one get completely away from me.

Another process question: how do you write with a partner?

Having worked in TV, and done celebrity as-told-to projects, I’ve probably collaborated with forty different people, and every partnership is different. Some use the “hot typewriter” where one person starts a story, gets to a stopping point, and turns it over to the next. In other modes, one writer does a first draft, the other does a polish.

With Heaven’s Shadow, David and I used the hot typewriter method for the storyline… much discussion, David doing several pages, more discussion, Michael doing the next pages.

| Hard SF has always been a relatively small subset of the SF universe: Larry Niven, one of hard SF’s finest practitioners, was an anomaly when he first began publishing… in 1965. |

With the novel, I do the first draft, David polishes, edits, rewrites. If there’s a problem, we talk it out. So far we haven’t had big issues… Just the usual things: should this character die? If not here, then somewhere else? It’s all in service of the story.

We’ve never had a disagreement that got testy. Indeed, in all my other collaborations, in whatever form they were, the only fights I ever had were over workload and showing up to get things done…

There’s a great short story I read once about two college students assigned to co-write a story—a guy who keeps writing military sci-fi and a woman who keeps writing weepy romantic fiction. They start each section by killing off the other’s characters. It’s a riot (and I’ve never been able to find it again.)

Heaven’s Shadow is near-term science fiction. That puts certain constraints on you. You cannot suddenly invent a super gadget or an alien with telekinesis to get you out of a corner. You’ve written a lot of near-term science fiction. Do you like the constraints? Or are there benefits to near-term sci-fi?

Heaven’s Shadow and to a greater extent, Heaven’s War, let you do both: make use of existing technology (which can be a bit of a straightjacket, especially when talking about propulsion, space suits, etc.) while also developing wilder SF gizmos.

What is Heaven’s War?

It is the direct sequel to Heaven’s Shadow. The twin “objects” that Keanu launched to Earth have scooped up two groups of humans and returned them to the NEO… where they are forced to learn to survive while trying to discover why they were taken.

(Just to spoil it for the readers: he’s referring to Keanu Reeves. Honest.) When do you expect to finish this trilogy?

The third book, Heaven’s Fall, will be written in 2012 and published in 2013.

What have been the biggest science fiction influences on your writing, both overall and more recently?

David will tell you Jack Vance, Gene Wolfe, Allen Steele, and Jack McDevitt. I will cite Steele and McDevitt as particular influences on this project, as well as Heinlein (every bit of SF I write seems to have echoes of Heinlein), Gregory Benford, Greg Bear, John Varley, Larry Niven & Jerry Pournelle, and especially Arthur C. Clarke.

Do you regularly read other science fiction? More broadly, what do you read?

| Given that, to my mind, SF readers are more likely to be drawn to e-readers than consumers of most popular fiction, I think some writers—including the hard SF folks—are going to become more popular than they ever would have in print. |

I’m a huge fan of Neal Stephenson’s work, from Cryptonomicon through The Baroque Cycle to the recent Anathem, which is brilliant. I just finished Paolo Bacigalupi’s Wind-Up Girl; have been reading George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire (not SF, but a cousin… and George is a great SF writer, too). Mary Robinette Kowal’s Jane Austen-esque Shades of Milk and Honey. Connie Willis’ Blackout/All Clear novels. I read Asimov’s every month, and try to keep up with Analog, F&SF, Tor.com, Locus, Lightspeed, and SF Signal, to name a few fiction and non-fiction SF sites or pubs.

David reads some of the same, but is probably more familiar with some of the new UK space opera folks like Charles Stross, Alasdair Reynolds, and Adam Roberts than I am.

Recently at Comic-Con in San Diego you spoke on a panel about realistic science fiction (“speculative fiction” in the program). Have you read any of the works by your fellow panelists?

If you mean, say, Vernor Vinge, the answer would be yes, I’ve read several books and some of his earliest stories, all the way back to the wonderful “Apartness,” which was in The World’s Best SF: 1965. I’ve probably read a dozen Greg Bear novels. A couple of my other panelists were people I met for the first time that day.

We are supposedly seeing a renaissance of hard science fiction. Do you think that’s happening? Where do you think the genre is going?

I don’t think “renaissance” is the right term, unless you want to go back to the late 1990s and the increased visibility of work by British writers like Paul McAuley, Reynolds, Stross, and Roberts. Niven, Steele, Poul Anderson, Charles Sheffield, Nancy Kress, and Kim Stanley Robinson (not often thought of as a hard SF writer, but I think so) and others were still being published and often winning awards. Hard SF has always been a relatively small subset of the SF universe: Larry Niven, one of hard SF’s finest practitioners, was an anomaly when he first began publishing… in 1965.

Where SF is going is going to be determined by how it’s published. Given that, to my mind, SF readers are more likely to be drawn to e-readers than consumers of most popular fiction, I think some writers—including the hard SF folks—are going to become more popular than they ever would have in print. And I wouldn’t be surprised to see the SF short story world—the only significant market for short fiction I know of—growing in sales and visibility, too.

What’s your dream project? Movie or book?

I can’t narrow it down to one—a typical failing. I’ll limit this to books, since I always have a couple of TV or film projects on the boil.

Non-fiction: An expansion of my recent Air & Space article on George Abbey, the single most influential figure in human space flight over the past generation.

Fiction: I have a contemporary fantasy novel in mind titled (at the moment) Tower of Baghdad.