Defending Apolloby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Make no mistake: Apollo 18 is no Apollo 13 by a long shot. |

Apollo 13 made it possible for both Gene Krantz and Chris Kraft to publish high-profile books, and made Jim Lovell—the real one—famous all over again. What made the event even sweeter was that it gave Tom Hanks the juice he needed to convince HBO to film the outstanding miniseries From the Earth to the Moon.

Make no mistake: Apollo 18 is no Apollo 13 by a long shot. It’s a small-budget horror movie involving a whole lot of people that you’ve never heard of. The reviews have not been kind. Jeff Foust reviewed it here three weeks ago:

The problem with Apollo 18 is not with trying to pass itself off as a depiction of actual events. No, the problem with the movie is that it’s not that good. While the film is not terribly long—barely 80 minutes until the closing credits begin to roll—at times it appears to drag on without building up much tension. It takes a long time for much of anything to happen, and, thanks to the trailers released in advance of the film, much of what might be considered plot twists or surprises have pretty much already been given away. The dialogue, when not reasonably accurate technobabble, is trite and predictable. In short, it’s just not that entertaining.

While I generally agree with those comments, in all the criticism a little perspective has been lost. Apollo 18 was made on a shoestring budget—reportedly $5 million, which is less than most of the television pilots that just debuted for the fall season, most of which will be gone by March. It has already made more than $25 million domestically. Compared to 2009’s Moon, which was a far better film in many ways and packed an emotional wallop that this movie lacks, Apollo 18 is a success. The rule of thumb is that a movie has to make two to three times its budget in order to break even, so Apollo 18 has already made a modest return on investment and will make its backers more money when it goes to DVD and television.

Personally, I’m looking forward to the DVD release. I’m hoping for some DVD extras—perhaps a short making-of documentary, or a commentary track—that can answer some questions. Some of these questions are technical, like how they made the film look the way it does. But I’m also hoping that the filmmakers answer the biggest questions of all: how the film got funded and why it got made.

The film is clearly what Hollywood calls “high concept,” meaning that its plot can be summed up in only a few words. Obviously the people who came up with the idea sold this film as “Paranormal Activity in space.” That was probably more sellable than “ghost story on the Moon,” but a space ghost story is what Apollo 18 clearly is.

| Despite all its flaws, Apollo 18 deserves credit for the things it does get right. |

The idea of a ghost story on the Moon is a pretty clever one when you think about it. The isolation, the pressure, the danger, all make for a great setting for such a story. Lots of other movies have tried to adapt the horror genre to a science fiction setting. Ridley Scott’s classic Alien was nothing if not a haunted house in space. Many other films followed it, most doing a lousy job. Apollo 18’s writers recognized that the Apollo program, when viewed from the perspective of the astronauts themselves, had the potential to be very creepy. After all, imagine being the only two men on an empty world and then hearing a noise from outside the spacecraft…

Unfortunately, Apollo 18 used the by now tired gimmick of “found footage,” meaning amateur-looking film that was supposedly found after—this is not really a spoiler—the people who filmed it met an untimely demise. The audience is voyeur, seeing the events that transpired and knowing that things did not end well. The technique has been around awhile, but it really took off with The Blair Witch Project, has been seen more recently in Paranormal Activity (1, 2, and now 3), and arguably peaked with Cloverfield (a film that I thought was great, but others hated, and one film critic somewhat justifiably derided as a 90-minute gimmick). Found footage inevitably means jerky cameras, grainy footage, and a raw and unpolished feel. It does not give actors the ability to explore their craft.

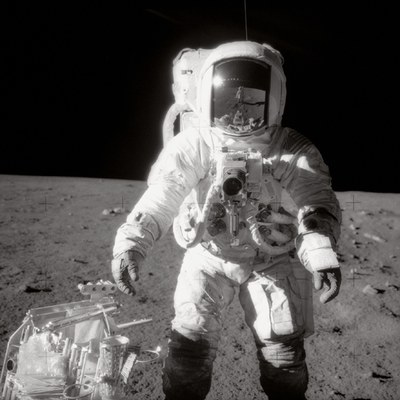

Despite all its flaws, Apollo 18 deserves credit for the things it does get right. The look of the film is realistic. Numerous scenes look as if the actors are really on the Moon. The harsh light and shadows and the pitch blackness are accurate, and some of the scenes of an astronaut on the lunar surface, if you froze them, would look almost exactly like Michael Light’s digitally restored Apollo photographs in his book Full Moon. The sets and props, such as the spacesuits and lunar module interior, are very accurate. It will be interesting to learn where the filmmakers got them and how they tried to make everything look as realistic as possible.

Other technical details are remarkably accurate as well. A key aspect of the story is that the astronauts are at the lunar south pole, where some craters are perpetually in shadow and thus dangerously cold. Descend into a shadowed crater and you could freeze to death in seconds. One criticism I read on the Internet was that the film featured the wrong version of the Soviet LK lunar lander. Several are in museums and the one in the film is apparently based upon the least accurate version that still exists. This is nitpicking, however, and glosses over the rather amazing fact that the filmmakers tried to accurately depict a Soviet spacecraft that 99.9% of their audience was unfamiliar with. They could have just as easily chosen to design their own Soviet lunar lander, accuracy discarded in favor of coolness.

| There were two movies this year that featured the Moon, and the Apollo program, as major parts of their story. Apollo 18 is certainly a more welcome addition to the genre than a noisy film about transforming car robots. |

Another thing that the film gets right is its story. Even if you do not consider the idea of a ghost story on the Moon brilliant, you have to concede that they thought out the story details. Before the film debuted some questioned the absurd idea that an Apollo mission could be hidden from the public. Saturn V rockets make a lot of fire and noise when they launch. But the film has an explanation for this: a rocket was launched, but ostensibly into low Earth orbit. All that the government concealed was that it really went to the Moon. Because most of the audience is not going to know exactly how many Saturn V rockets were launched during the 1970s, it’s not a stretch for them to believe that another Skylab was launched as a cover story.

Similarly, the film has a good explanation for why this mission was secret. The astronauts traveled to the lunar south pole to install Earth-staring sensors for the Department of Defense. It’s not an idea that stands up to much scrutiny if you understand the military space program—the Moon holds no strategic military value or there would be astronauts up there right now—but it’s possible to squint a little and accept such a story. Perhaps the sensors were intended for detecting nuclear explosions in space, something that the US Air Force did develop high-flying spacecraft to monitor. Anyway, the writers deserve credit for trying to develop a plausible plot driver.

Equally important, the movie has consistent internal logic, meaning that once you accept the premise, there are no gaping plot holes or inconsistencies that undermine it. In fact, one of the few pleasures of the film is watching how cleverly the filmmakers explained some of the things that the audience must have been wondering. For instance, as the conspiracy unfurls, one of the astronauts notes that this explains why the spacecraft is rigged with so many cameras, to broadcast what is happening back to Earth. There is another very good example late in the film that I won’t spoil here except to note that somebody came up with a clever way of having a person on Earth blackmail somebody at the Moon using actual technical jargon from the Apollo program.

I’ve been thinking about how Apollo 18 could have been a better movie. I can think of a number of tweaks: different actors, less shaky-cam, less reliance upon sudden shocks and a greater emphasis on the sheer creepiness of a supposedly dead world. The found footage premise, which might have enabled the film to get financing, may have also been its biggest inherent weakness—that required the director to make the film look jittery and amateur, and prevented him from making it look majestic and beautiful. It also limited how much his actors could actually do. One of the lost opportunities is that we never really get to like the characters and identify with them. I also think it would have been great if the closing credits would have used David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” (aka “Major Tom”), which would have been fitting.

There were two movies this year that featured the Moon, and the Apollo program, as major parts of their story. Apollo 18 is certainly a more welcome addition to the genre than a noisy film about transforming car robots. It is unlikely that it will be more influential, but I’m still looking forward to this DVD.