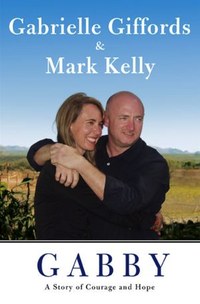

Review: Gabby: A Story of Courage and Hopeby Jeff Foust

|

| “Here’s the thing about NASA. It is populated by a lot of very nerdy smart people. They are drawn to the science of space exploration. A lot of them don’t see inspiration in their job descriptions.” |

In Gabby: A Story of Courage and Hope, Giffords and Kelly recount those events and more about their lives before and after the shooting. (The book is primarily written from the first-person perspective of Kelly; a final, brief chapter is written by Giffords.) The book eschews a straightforward chronological approach and instead skips around events both before and after the shooting, including the early lives of Giffords and Kelly and how the met, as well as her recovery and rehabilitation and his mission to the International Space Station.

While the book overall is a fascinating read, for space aficionados the most interesting passages may be those by Kelly describing his sometimes contentious interactions with NASA management. Immediately after the shooting he described himself as being in a “NASA-induced limbo” as “NASA officials weren’t sure they even wanted to keep me on the job” as commander of STS-134. He did have the support of his twin brother Scott, also a NASA astronaut and on the ISS at the time of the shooting, who reminded him, “You’re trained to put aside personal issues, to focus on your mission.” He also knew, he writes, that Giffords would want him to go: “‘Don’t even think of backing out,’ she would have told me if she could find the words.”

While Mark Kelly decided to remain on the crew, he met some resistance from his management. One of his managers, he wrote, said it made sense for Kelly to remain on the mission, but added, “I don’t know how it will look if you come back. The optics aren’t good.” (Kelly doesn’t identify this person by name, but did disclose his title as Director of Flight Crew Operations, a position held at the time by astronaut Brent Jett.) He proposed that Kelly go through an evaluation period that included T-38 check rides and shuttle simulator runs. He chafed at having to prove himself again, but accepted it, and ultimately won the approval of management to remain on the mission.

Kelly writes that the whole episode was evidence of a disconnect between NASA’s technical mindset and the more emotional views of the broader public:

Here’s the thing about NASA. It is populated by a lot of very nerdy smart people. They are drawn to the science of space exploration. A lot of them don’t see inspiration in their job descriptions. Gabby’s story had captured the public interest, and as people debated whether I should return to the mission, they were paying more attention to the space shuttle program. That wasn’t a bad thing. The American people pay NASA’s bills. It was good to have them engaged in what we were doing. But some at NASA considered their interest to be a distraction.

That wasn’t the only run-in with NASA management that Kelly recounts in the book. In the days before the originally-scheduled April launch of Endeavour, he describes taking Giffords out to the pad in a convertible, only to get a call later from an unidentified manager complaining that he shouldn’t have been near the pad (they were fueling the shuttle’s maneuvering thrusters at the time) and that he was speeding—hardly an unusual occurrence, he argued. “[T]o me, it was classic NASA Astronaut Office bulls—t: Try to track down people’s little misdemeanors and then rag on them over them,” he writes.

| Kelly also describes how he used the lessons of NASA’s failures in the treatment of Giffords. He ascribed the losses of the shuttles Challenger and Columbia to “groupthink”, the idea that “none of us is as dumb of all of us.” |

After the mission, he writes he was asked, as part of his mission debriefing, to “say something negative” about his fellow crewmembers, something he declined to do. “[I]t’s like they want to make sure they have some negative evidence they can point to if they want to deny someone a flight assignment or a specific position or role,” he writes. When he complained about that and the perceived lack of support from the astronaut office at the debriefing, he recalled, one unnamed manager exploded, calling those complaints unwarranted in a time when the shuttle program was winding down and thousands were being laid off. Kelly said he was just trying to get across the point that “the culture within the astronaut office had become rather negative over the last several years.”

Kelly also describes how he used the lessons of NASA’s failures in the treatment of Giffords. He ascribed the losses of the shuttles Challenger and Columbia to “groupthink”, the idea that “none of us is as dumb of all of us.” When doctors were meeting in the days after the shooting about how to carry out surgery to repair Giffords’s eye socket, Kelly reminded them of groupthink and singled out the youngest doctor in the room, asking her if she agreed with the group’s consensus on how to perform the operation. When she did, he approved, and the operation went off successfully.

Kelly, who recently retired from NASA and the Navy, doesn’t talk much in the book about his post-shuttle future. (Not surprisingly, given his criticism of NASA management, he said he didn’t think he wanted “a desk job in the astronaut office.”) He does describe going to London at the invitation of Sir Richard Branson shortly after the STS-134 mission to speak with a group of businesspeople. “Maybe there was a way to be involved somehow in his space exploration efforts,” he said, referring to Branson’s Virgin Galactic suborbital space tourism company.

Lest one think Kelly’s view of NASA in Gabby: A Story of Courage and Hope is wholly negative, he does praise many in the agency, from his fellow STS-134 crewmembers and other astronauts to NASA administrator Charles Bolden. “Leadership begins at the top and it was nice to know that Gabby and I had a friend in Charlie,” he writes in the book’s acknowledgements. And the book’s message is a positive one: as its subtitle states, it is indeed a “story of courage and hope”. And it’s likely we’ll be hearing a lot more from both Giffords and Kelly in the years to come.