Red Planet bluesby Dwayne A. Day

|

| We can only hope that the Russians will be smart in how they recover from this stumble. They could start by learning from past American experience and failures. |

However, the Fobos-Grunt story took an ominous turn soon afterwards with comments from Russian President Dmitri Medvedev. “Recent failures are a strong blow to our competitiveness,” Medvedev told reporters during an interview. “It does not mean that something fatal has happened, it means that we need to carry out a detailed review and punish those guilty.” That would have been bad enough, but Medvedev continued: “I am not suggesting putting them up against the wall like under Josef Vissarionovich (Stalin), but seriously punish either financially or, if the fault is obvious, it could be a disciplinary or even criminal punishment,” he said.

The Russians are currently 1 for 19 at Mars, which you’d think would convince them to pick a different planet, like Venus, where they’ve been more successful. In contrast, NASA has been amazingly successful at Mars, with three spacecraft currently operating there and another (knock on wood) on the way. But it is stupid for the United States to gloat over the Fobos-Grunt failure, and we can only hope that the Russians will be smart in how they recover from this stumble. They could start by learning from past American experience and failures.

According to Anatoly Zak, at least some Russian scientists have floated the idea of building a replacement spacecraft. But others have broached the possibility of putting a Russian Mars lander on a European Mars spacecraft scheduled for launch in 2016 (one problem is that the Europeans want to build their own lander, although they may not be able to afford it).

Before discussing what the Russians should do, it is worth considering what they should not do. The first thing they should not do is engage in the bloodletting that Medvedev seems eager to pursue. The Russians will conduct a failure investigation, but the best move would not be to fire or otherwise punish specific individuals—which will only accelerate the brain drain—but keep them in their posts. There are good reasons for this: They need to learn from their mistakes, and they are already short of people. The people who will learn the most are the ones who are responsible. The next time they conduct a planetary mission—and we can hope that there will be a next time—the mission will be stronger if they have people who have experienced failure, learned from a failure investigation, and thereafter do their utmost to avoid failing again. In addition, the Russian space science program suffered a substantial brain drain in the past 20 years, and it is best if they keep all the ones that they can.

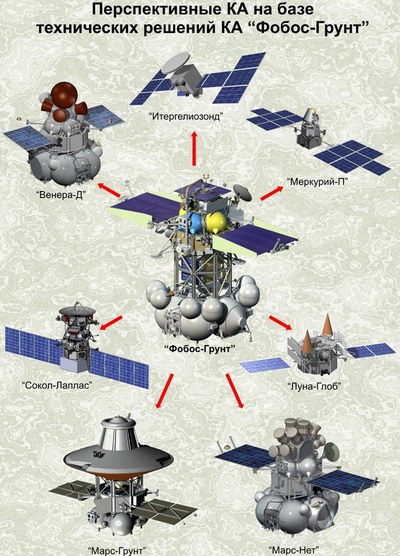

Russia has ambitious plans for future planetary missions, as this slide from a 2010 presentation illustrates. (credit: Lavochkin Association) |

Another thing they should probably not do is build another Fobos-Grunt. The Russians undoubtedly have spare parts sitting around, and they certainly have a lot of blueprints and plans left over (although that is not a given: NASA built the Spirit and Opportunity rovers so quickly that designers did not keep extensive records, making it harder to copy the design in the future). There will certainly be some pressure to fix the problems with Fobos-Grunt and try again. But Fobos-Grunt was too ambitious for a space program that lacks experience and personnel. The problem with adding instruments and tasks to a mission is that the complexity doesn’t add, it multiplies—every instrument has to draw power and push data, and so the electrical and data buses get more complex and the failure modes increase. Fobos-Grunt was an example of what NASA used to call “Christmas Tree” missions, where everybody hangs their ornament on it. Mars Observer was the classic American example of a spacecraft that ended up far more ornate than it needed to be for a mission to Mars. It failed in 1993, before ever reaching its destination.

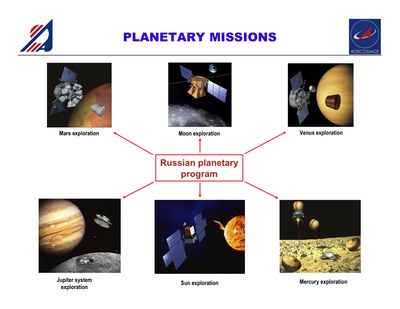

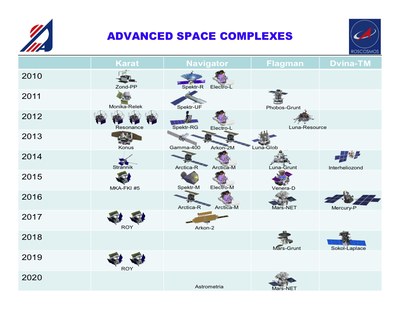

Something that the Russians probably should also do is look at some of the other plans that they have for planetary missions and ask hard questions about them. It is unclear how the Russians actually select their space science missions, although they seem to select missions that NASA is not doing and that also have a certain wow-factor. According to a 2010 Lavochkin Association presentation on upcoming space missions, the Russian science community has incredibly ambitious—and totally unrealistic—plans for the near-future. One slide depicts 33 spacecraft missions planned from 2012 to 2020, including lunar missions; a Venus orbiter, balloon, and lander; Mars network and sample return missions; and even a Mercury lander. Considering that in the past decade the Russians have launched three space science missions, including Fobos-Grunt, it is impossible to believe that they will launch four to five missions a year for the next eight years.

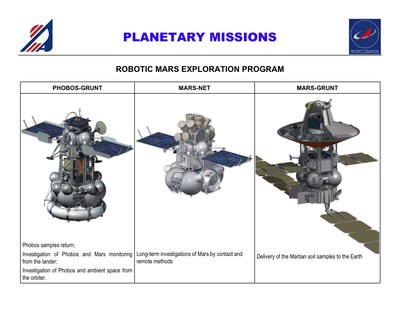

Fobos-Grunt was to be followed by future Mars missions, including a Mars sample return mission. (credit: Lavochkin Association) |

Fobos-Grunt was also supposed to be the first of several new planetary missions, with the hardware getting reused for other orbiters and landers. That is possible, assuming that a mission is successful. But Fobos-Grunt has not proven the hardware.

| The Russians have other spacecraft manufacturers, and changing their focus to small missions with faster turnaround and some degree of competition could be the most effective way forward. It is certainly better than a firing squad. |

There’s another issue as well: reusing components rarely makes sense except for communications satellites, which are generally built on a regular basis, the closest that spaceflight has to a production line. NASA has looked at the issue of reusing spacecraft buses numerous times. During the 1980s both the Mariner Mark II and the Planetary Observer proposals relied upon standardizing buses. The first Mariner Mark II became Cassini, and Mars Observer was to be the first of a class of spacecraft (Lunar Observer was to be the second, but was canceled because of cost and its association with the discredited 1989 Space Exploration Initiative). There are three problems with reusing hardware: one, planetary targets are different, with vastly different thermal environments and amounts of solar power; two, planetary missions are different, landers or orbiters, and divergent science goals leading to vastly different operating modes; and three, the long time between missions means that technology is obsolete and suppliers may be nonexistent by the time you try again. Indeed, NASA has discovered the latter problem even with Earth science missions. Unique spacecraft are not only the best solution, often they are the only solution.

An ambitious schedule of Russian planetary and other science missions. (credit: Lavochkin Association) |

Probably the best approach for the Russians would be to start smaller, with orbiters and with greater cooperation with other partners, such as ESA and NASA. Several years ago the Russians announced that after Fobos-Grunt, their next mission would be to the Moon, with the Luna-Glob lander. The Moon makes more sense than Mars for a program that is struggling to survive. But what they should also do is develop a program for the long-haul, with the ability to both collect science data and redevelop their lost engineering experience.

Finally, another lesson that the Russians could learn from the United States is the value of competition. Lavochkin has long had a lock on building Russian science spacecraft. In the United States, after the 1960s when several NASA field centers were responsible for planetary spacecraft, JPL developed a similar monopoly on their manufacture. In the 1990s NASA administrator Dan Goldin helped set up the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab (APL) as a competitor for small and medium planetary spacecraft. The results have been impressive, and currently several APL spacecraft such as MESSENGER and New Horizons are performing impressive missions. The Russians have other spacecraft manufacturers, and changing their focus to small missions with faster turnaround and some degree of competition could be the most effective way forward. It is certainly better than a firing squad.