Big comm, little mysteriesby Dwayne A. Day

|

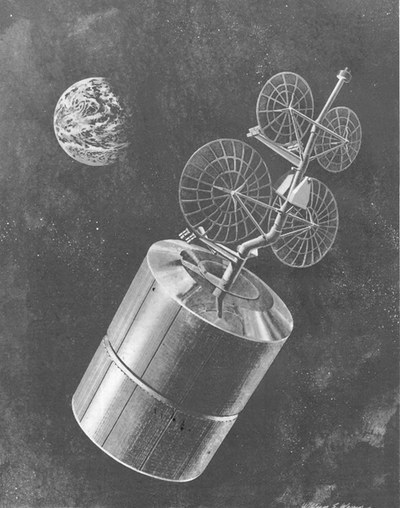

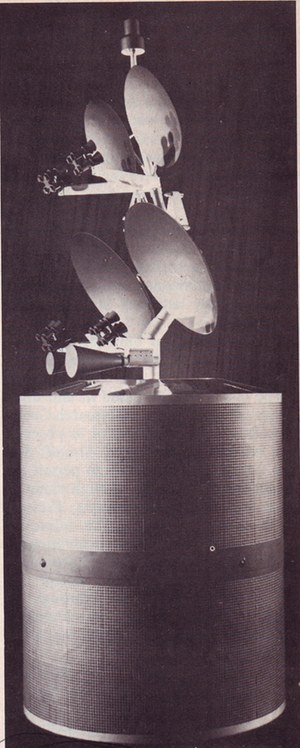

A model of Intelsat IVA. Unlike the original illustration, it has four solid (not mesh) antennas. (credit: Hughes) |

It is hard to write corporate history because corporations don’t open their archives except in rare situations. The evolution of Hughes’s highly successful satellite business is therefore mostly shrouded in corporate—and national security—secrecy. The evolution of specific satellite designs is equally problematic. Hughes engineers published several articles about the Intelsat IVA soon after the satellite type entered service, but none of them mentioned how the design evolved before it was finalized, or who deserves credit for different aspects of the design. That’s why the artwork and the model may tell a story.

Artist impressions, even physical models, don’t necessarily reflect the actual blueprints that a company’s engineers are drafting. But it seems likely that the Hughes’s artists who built the Intelsat IVA model, and later drew the Intelsat IVA illustration, were communicating with some of the engineers who were actually designing the new satellite. The evolving designs imply that at some point in the development, somebody—or several somebodies—determined that there was a better way of increasing the comsat’s communications capabilities than simply adding more dishes. At some point after that they went from solid dishes to wire mesh dishes. But at some point after that, they reduced the number of dishes from four to three. We can guess that these decisions resulted from the need to reduce weight as well as improvements in antenna design. But we’re guessing, we’re not confirming.

A photo of an Intelsat IVA satellite, showing two large and one smaller, rectangular mesh antennas. (credit: Hughes) |

What this example also demonstrates is that before a space mission is launched, the public primarily sees artwork of the spacecraft. After the mission is launched, they see photographs of what actually got built, and the artwork—especially if it is inaccurate—is usually never published again. In the case of the Intelsat IVA, the artwork revealed an unknown aspect of the satellite’s history. Probably worth more than 1,000 words.

Admittedly, the Intelsat comsats are not the sexiest spacecraft. But in addition to their role in the development of the commercial communications industry, there are some indications that they are closely related to several types of intelligence satellites also built by Hughes. Hughes built the JUMPSEAT signals intelligence satellites, first launched in 1971, and the Satellite Data System relay satellites, first launched in 1975. Considering that Hughes was producing a lot of spinning comsats at this time, it’s reasonable to assume that they are all related. Pictures of either of those would be worth way more than 1,000 words.