Not evolution—revolutionby Sam Dinkin

|

|

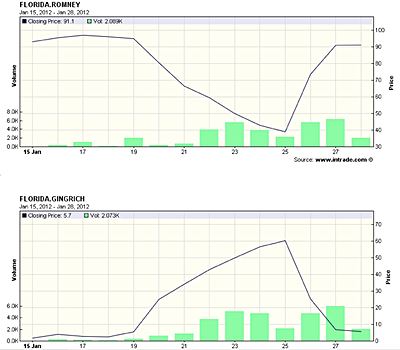

Light between the candidates

Ironically, Gingrich, Romney, and Barack Obama are not advocating that much difference in policy and not that much difference from George Bush’s policy as implemented. The Obama policy as articulated by the Augustine Committee continued a policy of gently encouraging domestic commercial alternatives to NASA self-supplying vehicles or obtaining them from Russia. Obama’s policy of go as you pay and building capabilities is the result of a meta-policy similar to Romney’s: appoint a panel of experts and do what they say. In Obama’s case, the composition of the panel resulted in a pro-commercial, decentralized policy that is in many ways a polar opposite of the administration’s health care and energy policies. The Obama space agenda ran into difficulty in Congress and the resulting compromise provides only limited reform.

| Ironically, Gingrich, Romney, and Barack Obama are not advocating that much difference in policy and not that much difference from George Bush’s policy as implemented. |

Romney’s meta-policy appears to be the same as Obama’s with the exception of the composition of the expert panel. The people who wrote an open letter in support of Romney seem like a likely group of people to pick to form the panel. They include Scott Pace, Michael Griffin, Gene Cernan, and Eric Anderson. It’s unlikely that Anderson, founder and chairman of Space Adventures, can bring Griffin around to supporting commercial space even now that Griffin is on the board of Stratolaunch (see “Stratolaunch: SpaceShipThree or Space Goose?”, The Space Review, December 19, 2011). Optimists might predict the experts will recommend limited evolution, but pessimists might predict frustration of recent limited evolution.

Neither the Obama or Romney policy rates to be very different from the Bush policy. While the Bush vision for commercial space was almost as clear as Obama’s, the Bush administration chose Griffin to implement the policy. This resulted in the vision being refocused as a more traditional NASA self-supply project before it was even proposed to Congress.

Gingrich’s policy differs little financially from the others. Devoting 10 percent of NASA’s budget to prizes is a very tiny change in proportion to the overall federal budget, comparable to the adoption of decentralizing welfare via block grants in 1996 instead of a more centralized Aid to Families with Dependent Children (about $2.4 billion/year). In contrast, Gingrich’s 15% optional flat tax proposal would put everyone in Romney’s tax bracket and shift hundreds of billions per year.

| This imminent price change in space access has not been taken advantage of in the Gingrich or Romney space policies and is only being considered for replacing Russian flights to the International Space Station in the Obama policy. |

That Gingrich’s prize proposal, to which he devotes less than $2 billion a year to prizes out of $3,500 billion in federal expenditures, can evoke such a heated debate (even for a few days) demonstrates both the outsize importance of space in the American psyche compared to its economic relevance and how closed space policy makers and the electorate are to large evolutionary changes in space policy. This latter tendancy is not surprising considering that our space policy for the last 40 years has been a series of homages to the Apollo years. The recent Bush attempt at recapitulating the glory years left NASA in danger of becoming a cargo cult that would take a revolution in spaceflight to shake up.

Gingrich also calls for subsidizing commercial providers the way that the Kelly Airmail Act of 1925 subsidized the early aviation industry. This is not that big a change from the Bush and Obama policy of COTS. Propellant depots and propellant subsidies might spark energetic fervor that Gingrich hopes for, but it rates to be a moot point. The cost barrier the energetic fervor is hoped to break through is going to be breached imminently.

Fighting the previous war

The policies of Gingrich, Romney, Obama, and Bush are all predicated on a cost environment that is on the brink of major change. The cost per pound and per flight to orbit has been in the tens of thousands per pound delivered for the Space Shuttle. Using the estimate of $1.5 billion in 2010 dollars per launch, that works out to $28,000/lb ($62,000/kg) of payload bay capacity to LEO. The NASA self-provided rockets under the Bush and Obama policies do not improve this situation.

In contrast, SpaceX is quoting delivering 2.2 times as much payload to LEO per launch. Using the Falcon Heavy for $80–125 million would offer a cost per pound of payload 25–40 times lower than the Space Shuttle. Further price drops may occur if Falcon Heavy becomes more reusable or other players begin low-cost competition. In an interview in September, Jeff Greason, an Augustine Commission member who until recently has been known for his conservatism in predictions for the future, challenged entrepreneurs to “start thinking about the business plans for—what if we DO have a way to get things up and down to space for, say, $500 a pound?”

This imminent price change has not been taken advantage of in the Gingrich or Romney space policies and is only being considered for replacing Russian flights to the International Space Station in the Obama policy. The change in cost is radical and opens up the technical and cost feasibility of missions that previously would have been considered way too heavy to be affordable. For example, the cost of hefting Von Braun’s 1952 70-person, 82-million-pound (37-million-kilogram) Mars mega-mission into LEO would only be $41–82 billion, or perhaps much less given the bulk discount for buying hundreds of launches. The current NASA budget is about $20 billion/year, so going to Mars is affordable for what is currently being spent in the name of space.

Alternatively, a bold president can ask the partners in the International Space Station for permission to put the ISS on a trajectory to Mars. It only weighs one million pounds (450,000 kilogams) and is already in orbit. Imagine that rockets and tanks to propel the space station would weigh one million pounds. Add 38 million pounds (17 million kilograms) of propellant to achieve Von Braun’s mass fraction of 95 percent.

| So what is the killer app that will settle the Moon? Is it surviving a disaster? Is it luxury condos? Is it platinum mining? |

At per-pound price levels to LEO of $500–1000, getting a pound to the Moon might be $2500–5000. Columbus’s voyage cost about 1.8 million maravedis, which was enough to buy 600 ounces of gold at 1492 prices; 600 ounces of gold costs about $1 million today, which might just be the cost of delivery of 400 pounds (180 kilograms) to the Moon. So if you can raise $1 million and so can 79 of your friends, you might be able to use a Groupon to buy a one-way trip to the Moon. $1 million may seem like a lot, but that’s just 25 years’ work at the average wage. For the top one percent of engineers or doctors, one can imagine working for passage to the Moon by agreeing to a three-year indentured servant contract with or without Gingrich’s proposed Northwest Ordinance for the Moon.

So what is the killer app that will settle the Moon? Is it surviving a disaster? Is it luxury condos? Is it platinum mining? The World Wealth Report 2011 details “investments of passion” of high net worth individuals (over $1 million) as 29% luxury collectibles; 22% art; 22% jewelry, gems, & watches; 15% other collectibles; and 8% sports investments. How soon until the rich are wearing jewelry made from Lunar material? When will a Moon rocket join yachts and jets as luxury collectibles?

When will the Moon become a destination for settlers and the wealthy? The first Spanish mission in California was 1769 and the Gold Rush was in 1849. It was 1946 when “Bugsy” opened the Flamingo hotel in Las Vegas. Will the first Moonrush be 2049? Is a revolution in space development on the way? Or has it occurred already without anyone noticing and getting on with space settlement?