The sounds of distant thunder: American intelligence collection on the Soviet space shuttle programby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Because the facility was over-built, it caused the American intelligence analysts to over-estimate the thrust of the rocket that would ultimately be launched there, eventually named Energia. |

Finally, in 1978, they spotted something. Reconnaissance satellites detected new construction at what they soon designated “Launch Site W,” concluding that “it will be used for the launch of a large, liquid-fueled space booster with a potential lift-off thrust of 42,300 to 44,600 kilonewtons,” or 10 million pounds of thrust. This was a big booster, with more thrust than a Saturn V rocket. The National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), which was part of the CIA and interpreted satellite imagery for the intelligence community, reported that this impressive launch thrust was “sufficient to place large and heavy payloads into Earth orbit.” Based upon new construction started at Complex J in late 1979, the NPIC concluded that the new rocket “will apparently also be launched from the former TT-05 superbooster launch facility, Complex J,” and use its mothballed assembly, checkout and transport facilities.

In reality, at the time Launch Site W was not a launch pad but instead a static test facility for full-duration testing of an entire rocket. According to Soviet space expert Jim Oberg, it was equipped with powerful hold-down arms for securing the rocket to the ground for a much longer time than the short hold-and-release necessary for an actual launch. Because the facility was over-built, it caused the American intelligence analysts to over-estimate the thrust of the rocket that would ultimately be launched there, eventually named Energia. The US intelligence community’s confusion was entirely understandable, because the site had nearly everything it required to actually launch the rocket, and eventually it was converted into a launch pad. It was where the first Energia rocket was launched, many years later. As a launch pad, Site W was way over-built, but as a test stand, it was what they needed. But this mistaken assumption also led to a mistaken conclusion. In actuality, the Energia’s launch thrust was 29,000 kilonewtons, or 6.6 million pounds—much less than the early estimate.

In May 1981, American reconnaissance satellites spotted efforts to modify the two large transporters/erectors that were used for the N-1 rocket. Structural members were next to the transporters and additional components had been brought in, apparently to serve as part of a new superstructure and cradle to hold a new launch vehicle.

The CIA pieced together other bits of intelligence and speculated that “the new booster will probably be used to launch a space shuttle-like vehicle.” This was based in part upon the sighting of what could have been a small-scale shuttle at the Kurumoch Rocket Engine Test Facility. More telling was a large runway under construction near Launch Site W at Tyura-Tam.

In reality, the spotting of the small scale vehicle at Kurumoch was a red herring, because Kurumoch had nothing to do with a Soviet space shuttle program. Bart Hendrickx, who wrote the definitive history of the Soviet space shuttle, does not know what vehicle the American reconnaissance satellites spotted there, but it may have led the CIA to draw conclusions that were not accurate.

By April 1982, a National Photographic Interpretation Center report noted that “the modification to Space Launch Site J1/J2 is progressing at a slow rate.” Construction crews had built additional propellant storage areas and modified the service gantry at one of the launch pads. “Modification to the service gantries at J1/J2 included the removal of the service platforms on the rotatable service gantries and the removal of the top 23 meters of the gantry at launch position J2,” according to the declassified report. In addition, the lightning towers were modified.

The CIA designated the new unseen rocket as SL-W, for “Space Launcher” at Launch Site W. They projected that the vehicle would be launched in 1984 or 1985.

| In March 1983 an American satellite got incredibly lucky, spotting the Soviet shuttle atop its Bison carrier aircraft which, embarrassingly, had run off a slick runway at Ramenskoye and gotten stuck in the mud. |

In August 1983, American reconnaissance satellites detected the beginning of construction of “eight probable instrumentation/tracking sites” at Tyura-Tam. By November 1984 they concluded that the new sites were probably associated with the Soviet space shuttle program. The sites were arranged in a “butterfly-shaped pattern centered on the runway” which was assumed “to be the prime landing runway for the Soviet space shuttle.” The sites did not “resemble any known Soviet aircraft or missile test range electronics facilities, nor do they resemble facilities associated with the U.S. Space Shuttle Program,” a CIA report concluded.

In December 1984, the reconnaissance satellites spotted another clue: a “space shuttle-associated support vehicle” near the airfield—essentially a tractor for towing the shuttle. “Recently, similar type vehicles were at the newly constructed space shuttle hangar at Ramenskoye Flight Test Center.”

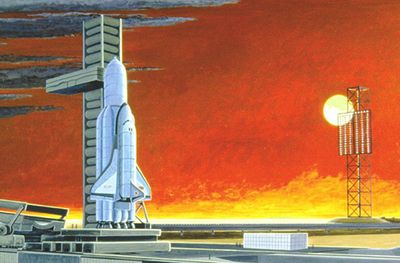

An illustration of the Buran and its Energia rocket on the launch pad at Baikonur. (credit: DIA) |

The bird

American reconnaissance satellites were photographing the new work at the launch site, but they had also detected other clues at other sites. At some date, still not known because the records remain classified, but possibly in 1982, American reconnaissance satellites spotted a full-size Soviet space shuttle at the Ramenskoye Flight Test Center, which the CIA also referred to as the “flight institute” (abbreviated as “LII”). In March 1983 an American satellite got incredibly lucky, spotting the Soviet shuttle atop its Bison carrier aircraft which, embarrassingly, had run off a slick runway at Ramenskoye and gotten stuck in the mud.

In December 1984 a satellite spotted a second shuttle:

“One shuttle is on a modified Bison in the flight institute (LII) area and a second is in the newly constructed shelter in the LII area. A shuttle without a tailcone (inside the shelter) is also seen for the first time. Two large, unique vehicles, probably tankers, are behind the shelter. One of the vehicles is backed up to the shuttle, possibly transferring some type of fuel.”

The satellite photos revealed a lot of detail:

“The presence of the shuttle in a hangar with facilities to test jet engines lends strong credence to the theory that the Soviet shuttle will have air-breathing engines for endo-atmospheric maneuvering.”

“The shuttle atop the modified Bison has two blisters on either side of the fuselage in the area where the tail cone is joined to the fuselage. These blisters were not seen on the shuttle when it was at Ramenskoye before the landing accident in March 1983. These blisters may be attachment points or air scoops for the air-breathing engines. The snow melt behind the Bison with the shuttle on top indicates that the Bison engines have been run up recently.”

| Although analysts determined that the Soviets had saved massive amounts of money by gathering up all of the data they could on the American space shuttle program, it is unclear if they fully understood just how incredibly expensive the Soviet shuttle program was. |

According to Bart Hendrickx, in December 1984 a second shuttle—a non-space-worthy vehicle similar to NASA’s Enterprise vehicle—was being prepared for a taxi run and another Buran test vehicle underwent a test flight atop the Bison. Eventually American reconnaissance satellites spotted a real Soviet space shuttle on its launch pad, and the Soviet government revealed its existence.

Assessing the evidence

While the satellites were looking down on the Soviet Union, intelligence analysts back in the United States were also crunching the numbers. Although they determined that the Soviets had saved massive amounts of money by gathering up all of the data they could on the American space shuttle program, it is unclear if they fully understood just how incredibly expensive the Soviet shuttle program was.

Now, over two decades later, the story of what the American intelligence community knew about the development of one of the most expensive Soviet space programs ever built is just becoming known, as the US government slowly pulls back the cloak of secrecy from its operations during the last decade of the Cold War.