Commercial crew in the spotlightby Jeff Foust

|

| “I look at every program in your budget and it seems to take a hit, except for the commercial crew,” Rep. Edwards. |

Bu a funny thing happened: while those proposed cuts have come up in hearings, they have recently been overshadowed by another aspect of the budget, NASA’s commercial crew program. In back-to-back hearings last Wednesday by key Senate and House committees, members rarely mentioned the Mars program cuts, and devoted far more attention to NASA’s request for nearly $830 million to continue the commercial crew program. That scrutiny, which featured some heated exchanges during last week’s hearings, suggests that commercial crew supporters face a long and possibly steep battle to secure funding this year.

“Irrefutable” numbers

The commercial crew program is getting that attention in part because of the size of its budget request. The final fiscal year 2012 appropriations bill gave the program $406 million, a compromise between the $312 million offered by the House and $500 million by the Senate. While the 2013 proposal for $829.7 million is actually similar to the original 2012 proposal for $850 million, to some in Congress it appears that NASA is asking for a huge increase for the program, particularly when the agency’s overall budget is effectively flat.

“I look at every program in your budget and it seems to take a hit, except for the commercial crew,” Rep. Donna Edwards (D-MD) told NASA administrator Charles Bolden during a House Science, Space, and Technology Committee hearing on Wednesday afternoon. “I wonder if you can tell me how we can expect support on this committee for an 104% increase when you have yet to provide to us, despite being asked numerous times, frankly, General, a credible cost and schedule estimate that justifies an annual funding stream.”

“I have a lot more difficulty understanding the rationale for cutting all of the worthy programs… in order to provide such a huge increase for the commercial crew program,” said Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), the ranking member of the full committee. “We basically have to take it on faith that your budget requests are neither too small or too large.”

Bolden argued that the requested funding was necessary to keep the program on track to start ferrying crews to the ISS by 2017, a date that has already slipped a year because of the reduced funding the program received last year. “The reason we’re asking for the $829 million is because we do not want to see it go to the right any more,” Bolden told Edwards at the House hearing. “The gap between now and 2017 is excessive. A gap that increases would be unacceptable, and that’s the reason we came back and asked for a restoration of funds for the commercial crew program.”

Others, while professing their support for the commercial crew program, worried about at whose expense it was being funded. The most notable example of this was at a hearing of the Senate Commerce Committee Wednesday morning. “Reviewing that budget… gives me great concern,” said Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) in her opening statement. She cited later in the hearing a combined cut of $326 million for the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) in the FY2013 proposal compared to the final FY2012 appropriations “and a corresponding increase of $330 million for commercial crew.” (The source of the $330 million wasn’t clear, since the actual difference between the FY2012 appropriations and the FY2013 request is actually over $420 million. She may have been referring to the authorized level of $500 million for both 2012 and 2013, or the Senate’s original FY2012 appropriations bill that also provided $500 million.)

Regardless, she was clearly unhappy that it appeared that SLS and Orion were helping pay for commercial crew. “I was frankly floored, as you know from our conversation,” she told Bolden, referring to an earlier conversation between the two, “that it would be so blatant to take it right out of Orion and SLS and put it into commercial crew, rather than trying to accomplish the joint goals that we have of putting forward both.”

Bolden responded that the additional commercial crew funding was needed to keep the program on schedule for entering service in 2017, and that SLS and Orion remained on track for a 2017 uncrewed test flight, with a crewed mission to follow by 2021. Adding money to the SLS and Orion programs, he added, would not significantly accelerate their schedules.

Hutchison was unconvinced, though. “You said everybody had to be cut some to make the priorities, but in fact, the commercial crew vehicle approach that you’re taking was not cut, it was plussed up from last year’s spending levels,” she said. “You are over-prioritizing the commercial and not being as concerned about keeping the people at NASA who would be able to stay involved” for future exploration programs.

| “We are not taking money away from SLS/MPCV,” Bolden said at one point. “But you are!” Hutchison exclaimed, cutting Bolden off. |

Hutuchison then proposed a solution for her concerns: reduce the number of companies involved in the commercial crew program to as few as two, which she said would free up money for SLS/Orion instead of spending them on companies that “are not going to be able to function if they don’t have these subsidies once you make a decision about who is going to do the vehicle.” Her idea was not a new one: at a hearing of the Commerce, Justice, and Science subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee the previous week, members asked presidential science advisor John Holdren if NASA could reduce the number of teams now, perhaps to a single “star team”, in the words of subcommittee chairman Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA), to save money.

Bolden disagreed, arguing that it was premature to select a single company now. As the debate continued between Hutchison and Bolden, the two appeared to become more entrenched in their positions, and the rhetoric hardened. “We are not taking money away from SLS/MPCV,” Bolden said at one point.

“But you are!” Hutchison exclaimed, cutting Bolden off. “It’s clear, it’s in the numbers, and it’s irrefutable. If you had the passion and the concern for the SLS and the Orion that you have for protecting whatever number of commercial companies that you want to put out there…”

“Senator, not to get personal,” Bolden interrupted in turn, “but my passion for SLS/MPCV exceeds anybody’s in this room.”

“Well, it’s not shown in the numbers, Mr. Administrator. That’s the problem.”

“Senator, I fight for SLS/MPCV just as much as I do for every other of the three priorities we have agreed to,” Bolden said, referring to support for the ISS (including commercial cargo and crew) and development of the James Webb Space Telescope as the other two priorities.

Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), who chaired the hearing, allowed the extended exchange between Hutchison and Bolden to go on for over 20 minutes before finally stepping in. He eventually said he supported increasing commercial crew funding, provided it didn’t come at the expense of SLS and Orion. “With a limited amount of money, we know we’re asking you do an awful lot,” he told Bolden. “What we need to do is work with you at coming up with a number for commercial and not, at the same time, sacrifice anything on the big rocket and Orion.”

Protecting safety

A second issue regarding the commercial crew program is congressional concerns about crew safety. When NASA decided in December to switch from a contract based on Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) to a Space Act Agreement (SAA) like that used for the first two rounds of the program (see “An about face for commercial crew”, The Space Review, December 19, 2011), it gave up the ability to require companies to meet specific NASA safety standards, given the legal restrictions of an SAA over a more conventional contract. NASA officials acknowledged at the time that there was a risk companies funded in the newest round might develop vehicles that don’t meet those standards, but it was mitigated by the fact that the standards they had to meet were published, and that future contracts to provide crew transportation services by those vehicles would require compliance.

| “There is no problem of safety with Space Act Agreements,” said Bolden. “I am responsible for safety, and as I have said from the day that I became the administrator, I will not jeopardize safety for crews.” |

But when Holdren appeared before the House Science Committee last month to discuss the administration’s overall R&D budget proposal, the first question he got from committee chairman Rep. Ralph Hall (R-TX) dealt with the commercial crew safety issue. “It’s my understanding that NASA can’t require the companies to meet any safety standards. I don’t know how that could have been left out,” he said, asking Holdren what NASA would do to ensure that these vehicles “ultimately are going to be safe enough to take NASA astronauts to the International Space Station?”

Holdren, apparently unfamiliar with that particular issue, said he wasn’t aware of the details. “I can’t imagine that NASA does not retain that responsibility” for ensuring crew safety, he said. “And if there is a problem in the agreements that would jeopardize that, I am sure we will fix it.”

At the end of February seven members of the House, led by Rep. Pete Olson (R-TX), wrote Holdren on that issue. “It is inexcusable for the Administration to spend hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayer funds on these nascent systems without the ability to define and impose the necessary requirements to ensure the health and safety of astronaut crews,” they wrote. “If safety is being jeopardized through improper contracting methods, we expect you to take immediate action to remedy the situation.”

The topic came up at both NASA hearings last week, with Bolden arguing that even without the ability to require conformance to safety standards under an SAA, the vehicles would be safe. “There is no problem of safety with Space Act Agreements,” he told Hutchison in the Senate hearing. “I am responsible for safety, and as I have said from the day that I became the administrator, I will not jeopardize safety for crews.”

Bolden told House members later in the day that he had been reluctant to switch from a FAR-based contract back to an SAA for the latest commercial crew procurement, but was convinced by agency officials that it would not compromise safety and would allow the agency to support more companies. With a FAR contract, he said, the available funding for 2012 would allow them to award only one contract, and “the subsequent costs on that contract would, I think, have been—I would not have been able to afford it.”

Congressman Chaka Fattah talks about the prospects for commercial crew funding during a forum on the program on Capitol Hill March 8. (credit: J. Foust) |

Industry’s response

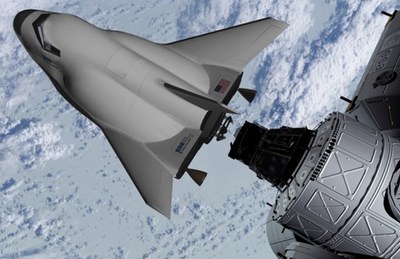

The day after the House and Senate hearings, the Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF) convened a panel of industry representatives on Capitol Hill to provide their own take on the commercial crew program. Officials with three of the four currently-funded commercial crew companies—Boeing, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX—as well as United Launch Alliance (ULA), which has an unfunded commercial crew SAA, made the case for continued funding to an audience of staffers and other interested parties.

“We need to get Americans into space on American spacecraft, and the quickest way you can do that is the path we’re on now,” said Mike Leinbach, a former NASA shuttle launch director who joined ULA earlier this year. Progress, he said, will be “fully dependent on the funding levels going forward”, and getting the requested funding of nearly $830 million in 2013 “would be a real boost to the system.”

Others also made the argument for full funding of the program. Boeing’s Keith Reiley said that his company’s commercial crew concept, the CST-100, could be ready to enter service as soon as the end of 2015 if fully funded. That, he said, “is why the funding coming out Congress is very important, not only for us but everybody at the table here.”

| Commercial crew “is a high priority for me, and a high priority for the administration,” said Fattah, but added it will be “a challenging environment” to win funding for it. |

The request for proposals for this latest round of the commercial crew program will also address an issue raised in the hearings: just how much these systems will cost to develop. John Roth of Sierra Nevada said that the current RFP requires companies to indicate how much they expect from NASA to develop their systems, and how much the expect to invest themselves, information not previously requested. “This will be the first time, on March 23rd, when the proposals go in, that NASA has full visibility for all contractors on how much money we need from NASA and how much our company’s going to put in,” he said.

Company officials also discouraged efforts to downselect to one or two companies in this latest round, saying more development work among several companies is still warranted. “This next round of commercial crew development is really a development contract,” said Adam Harris of SpaceX. “It makes sense to let a number of teams go forward and develop those concepts, and then when you’re getting to flights to the International Space Station, you’ll have a lot more data to make that decision.”

On the issue of safety, the CSF released a letter last week signed by Jim Voss, director of advanced programs at Sierra Nevada; and Garrett Reisman, CCDev-2 program manager at SpaceX. The two, both former astronauts, wrote to Rep. Olson and his colleagues that safety would not be compromised by NASA’s ongoing use of SAAs. “NASA has established safety standards that all commercial crew providers will have to meet before flying astronauts, and published them in its CCT-1100 series of documents,” they wrote. “Regardless of the content of NASA’s Space Act Agreements for development stages of the competition, we are treating these documents as firm requirements.” They added that in “no circumstance will a NASA astronaut fly in a commercial vehicle until NASA has certified that the vehicle has met every safety requirement.”

Although the rhetoric about commercial crew got heated early this year, it’s unlikely that in an election year the funding for the program, or NASA in general, will be quickly resolved. In brief comments at the CSF forum Thursday, Rep. Chaka Fattah (D-PA), ranking member of the House appropriations subcommittee whose jurisdiction includes NASA, said he expected that a final FY2013 appropriations bill won’t be completed after the November elections.

At that time, he said, “it will be an opportunity for the country to think clearly about when it is that we want to have the capacity, an American capacity,” to send astronauts to the ISS. “The quickest way for us to get there is through commercial crew, and the worst way to proceed along that line is by undercutting the funding.”

Fattah said that commercial crew “is a high priority for me, and a high priority for the administration.” However, he admitted that it will be “a challenging environment, given the overall fiscal circumstances relative to NASA” to secure full funding for the program. A lot may be riding on just how challenging that environment turns out to be for NASA, commercial crew companies, and their advocates.