Shattered glassby Dwayne A. Day

|

| By the early 1970s the American reconnaissance satellite program had achieved maturity. Despite this impressive technology, things could still go wrong. |

One of the stories that I included in the second article was about the time when one of the GAMBIT satellites accidentally fell on England in the early 1970s. Allegedly, a US Air Force officer heard about the discovery of the debris while sitting in a pub. This story was not in the officially released and heavily blacked-out history. It was told to me by a source who had gotten it from a former senior intelligence official. I trusted my source, and he trusted his source, but we both knew that the source was relying on a memory from many decades ago. Thus, there were likely gaps in his memory, and possibly places where real gaps had been filled in with some embellishments. That’s the nature of oral history—you have to expect that even those with first-hand knowledge start to believe their own or other people’s exaggerations.

Now that the official histories have been declassified, it is possible to get a little better picture of what actually happened. In this version of events, no US Air Force officer walks into a bar.

Falling GAMBIT

By the early 1970s the American reconnaissance satellite program had achieved maturity, with satellites regularly returning imagery of Soviet targets at incredible resolution, good enough to reveal people on the ground. Despite this impressive technology, things could still go wrong.

On May 20, 1972, the US Air Force launched a Titan III Agena D rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. This was GAMBIT mission 4435. Although this was a GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite, like the Air Force had launched 34 times before, it included a number of hardware changes from its predecessors, based upon lessons learned in GAMBIT and other programs. One such change was a Gemini Uniform Mixture Ratio engine installed in the secondary propulsion system. The GUMR engine could enable the rocket to lift an extra 90 kilograms (200 pounds), or change inclination. A Backup Stabilization System allowed the use of surplus gas in the primary control system, which could increase the number of times that the spacecraft could rotate its camera to either side of its ground track. The extra lift capacity allowed the spacecraft to carry heavier “magnum” model batteries, a total of ten. This increased the orbital lifetime to 30 days. Mission 4435 would be the longest-lasting GAMBIT mission to date.

Except it didn’t work out that way.

Despite all of the modifications, Mission 4335 was doomed. A pneumatic regulator, used for delivering control gas to the Agena, failed to operate properly during the ascent. The Air Force tried to predict the impact point for the rocket, concluding that it was somewhere over South Africa. But probably because the reentry footprint was so big the Air Force did not attempt to search for it. The NRO, which ran the reconnaissance satellite programs, quickly forgot about 4335 and focused on launching the next mission.

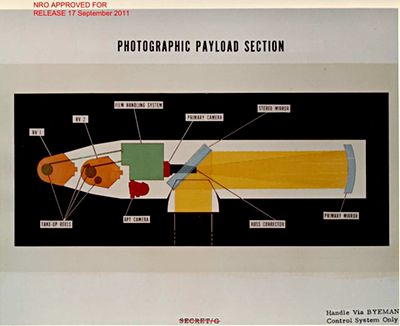

Illustration of the photographic payload on a GAMBIT satellite. (credit: NRO) |

Charred debris

Three months later, Dr. Walter F. Leverton of the Aerospace Corporation, which provided engineering support to various classified and unclassified American intelligence and military space projects, was visiting his company’s London offices. While there he heard from a co-worker about some “interesting space material” that had been recovered in England earlier in the year. Leverton was interested in the story and arranged to visit the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough.

| Apparently the fact that any debris reached the ground was a surprise to program officials, because at the time they had invested significant effort into determining how much material would survive reentry and their models indicated that everything should burn up. |

When Leverton arrived, the RAF people showed him some objects, including a spherical titanium pressure vessel a foot in diameter and some circuit boards that had US markings. But the most telling things he saw were several chunks of glass that could be assembled into a pie-shaped wedge with a 25-centimeter (10-inch) edge. This was no ordinary glass, but was backed with a still-classified material manufactured by Eastman Kodak and characteristic of the optics used in the GAMBIT-3 satellite.

Leverton was informed that all of the pieces had been found 120 kilometers (75 miles) north of London in an eight-kilometer (five-mile) radius where they had fallen on or around May 20, 1972.

Leverton realized that this was debris from a GAMBIT satellite and called his project office in California using private channels—probably a secure telephone—so that nobody else learned about the discovery. He arranged for the material to be transferred back to the United States. Later analysis confirmed that the debris was from Mission 4335.

Apparently the fact that any debris reached the ground was a surprise to program officials, because at the time they had invested significant effort into determining how much material would survive reentry and their models indicated that everything should burn up. The circuit boards and pieces of glass from Mission 4335 proved that this was not the case. (See: “Black Fire: De-orbiting spysats during the Cold War,” The Space Review, October 25, 2010.)

Stories still incomplete

The official histories now confirm the story, but they remain maddeningly sparse on details. Until the NRO declassifies more documents pertaining to the mission, we are left with an incomplete story of what happened.

Perhaps much less significantly, the histories do not indicate who found the debris in the field and how it came into possession of the Royal Air Force. Perhaps it was an RAF officer who walked into a pub and overheard a farmer discussing the debris he found while plowing his field.

Or maybe not.