Code of Conduct: corrections, updates, and thoughts going forwardby Michael Listner

|

| Even with a new push to adopt a Code of Conduct, there are uncertainties whether it will be successful, and, more importantly, how the EU and the US define success. |

On June 5, 2012, the European Union (EU) officially launched a multilateral diplomatic initiative to discuss and negotiate an International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities. The meeting was held in Vienna, Austria, the day before the 55th Session of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) convened. Maciej Popowski, Deputy Secretary General of the European External Action Service, chaired the meeting, which included 110 participants from more than 40 countries. The EU introduced a revised version of its draft Code of Conduct, with revisions based on comments received during bilateral meetings with various partners, including the United States.

No substantial negotiations took place during this initial meeting; however, significant negotiations will start at the Multilateral Experts Meeting of October 2012 at the United Nations in New York. All UN member states will be permitted to participate, with a goal of agreeing to a Code of Conduct in the second half of 2013. The one notable difference with this attempt at negotiating a Code of Conduct is that the EU has delegated the task of information dissemination and exchange of views on this concept of the Code of Conduct to the UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR). UNIDIR will perform this function in conjunction with diplomatic efforts.1

Even with a new push to adopt a Code of Conduct, there are uncertainties whether it will be successful, and, more importantly, how the EU and the United States, who is supporting this effort along the EU, define success. As I’ve noted before, there are stumbling blocks for the Code of Conduct to overcome before it will adopted. For instance, one of the stumbling blocks in the original draft Code was the US concern that its right to self-defense of its space assets could be compromised during the prior Code of Conduct effort. This concern led to the United States announcing early this year that it would not support the EU draft.

Another concern, which the United States is reportedly sensitive to and has stressed, is the unease voiced by emerging spacefaring nations, such as India and Brazil, that their views were not being taken into account. Both these nations, although having lesser space capabilities than some of the other nations present at the talks, do have promising space programs that will likely influence the outer space environment. It is notable that the United States does have good diplomatic relationships with both these nations, and it is understandable that the US would want to promote those countries’ interests as its own. However, despite the support for them, is no certainty that the concerns of either nation will be allayed so that they would be comfortable signing on to the measure, especially since the Code will not be legally binding.

| China’s reluctance to participate in, and otherwise support the negotiations for, the Code of Conduct may also lie with the fact the Code would implicate China’s national space policies. |

An added wildcard to the Code of Conduct discussions is China. China, like India, has felt that it has been left out of consultations on the Code of Conduct up until now. Micah Zenko at the Council on Foreign Relations said recently that China will be absent from the upcoming negotiations.2 However, this concern seems to run counter to Chinese public statements, such as the one made by Ambassador Cheng Jingye, head of the Chinese delegation at the recent COPUOS meeting, that the country seeks greater cooperation in outer space towards the end of preserving sustainability.3 Given this ideal, it is questionable whether being excluded from prior negotiations is a legitimate reason for China to avoid future discussions about the Code of Conduct, or whether it is a means of protecting its own approach to space sustainability, including its efforts in the UN Conference of Disarmament and its co-sponsorship of the Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space (PPWT), which could be weakened or even nullified by a successfully implemented Code of Conduct.

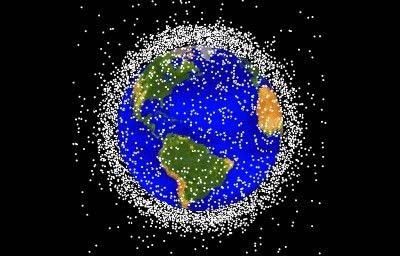

China’s reluctance to participate in, and otherwise support the negotiations for, the Code of Conduct may also lie with the fact the Code would implicate China’s national space policies. While China has articulated a public space policy of sorts in its December 2011 whitepaper, the policies contained within it lack the specificity and transparency that the Code of Conduct would encourage. Furthermore, one of the cornerstones of the Code Conduct is space debris mitigation by spacefaring nations. China has indicated in the past that space debris is a low priority and certainly ascribing to the behavior encouraged by the Code of Conduct would seem to run contrary to current Chinese interests.

China is not the only wildcard in the next set of negotiations over the Code of Conduct. Like China, Russia expressed reservations over the attempt to adopt the original draft of the EU Code. Russia is a co-sponsor of the PPWT with China and, as such, stands to lose substantial soft-power influence if a successful Code of Conduct is implemented. Russia has noted that transparency and confidence-building measures (TCBMs) such as the Code of Conduct have been used in the past to address issues relating to space activities, and that it has used unilateral TCBMs itself in regards to notifications of launches and the pledge not to be the first to deploy space weapons.

However, Russia has stated it will likely continue to support the use of TCBMs, which would likely include the Code of Conduct, if only to lay the groundwork for adoption of the PPWT and that the adoption of the PPWT would be the most important confidence-building measure in outer space. This argument is a non-starter for the United States in particular, considering that recent reviews by the US State Department have come to the conclusion that the PPWT does not meet the criteria for adoption as enunciated in its National Space Policy.4

| Sometimes awareness of a problem itself is enough to convince nations that they have to take corrective and preventative actions on their own. |

This fact does not sit well with Russia and may dissuade it from signing onto a Code of Conduct. The effect of China and Russia’s likely absence from a signed measure could deem the Code itself a failure. Going forward, the lack of participation of China and Russia could persuade other nations not to sign the measure as well, and this would place the EU and the United States in the position of having to redefine success.

Even the US should not be considered a sure thing when it comes to signing onto the new version of the Code, even though it has thrown its support behind the effort. Throughout 2011 statements reported by the media and diplomatic officials all suggested that the US would sign the draft EU Code; however, as was seen with the January 2012 announcement, the US government concluded that the EU Code was inconsistent with its national security interests. Likewise, unless this revised Code can meet the national security expectations of the United States, it could conceivably suffer the same fate as its predecessor.

However, even if the attempt at the new Code of Conduct fails to achieve whatever measure of success its proponents define for it, progress in a sense will be made in that the nations of the world gathered and recognized the validity of the issue of space security. Sometimes awareness of a problem itself is enough to convince nations that they have to take corrective and preventative actions on their own. Such a recognition here would fulfill the intent of the Code of Conduct in spirit if not in a signed measure. Only as negotiations begin in earnest will we see how this new Code effort will fare, and whether the nations of the world choose on their own to act responsibly in outer space regardless of a promise to do so.

References

1 Press Release, EU launches negotiations on an International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities, Brussels, June 6, 2012

2 Jessie Wingard, “The battle for cooperation in space begins”, DW, June 14, 2012.

4 The National Space Policy of 2010 states in part that “The United States will consider proposals and concepts for arms control measures if they are equitable, effectively verifiable, and enhance the national security of the United States and its allies.”