Feedback loopJohn Hickman talks to author Allen Steele about science fiction and space as a frontierby John Hickman

|

| So unless we want to slide into the decadence that marked the decline of great civilizations of the past we’re going to have to seriously consider going somewhere else. And anyone who’s read my work knows what my idea of that “somewhere else” is. |

Steele: When you look at history, it appears that the discovery and opening of new frontiers has always been necessary to keep ourselves from cultural stagnation. In his book Dreaming Up America, Russell Banks states that our country’s hallmark achievement—in fact, the thing which defines American history more than anything else—is the abolition of slavery, and that this could have only happened in the New World, because slavery had become so much a part of the Old World that such a fundamental social change would have been impossible over there. And you don’t have to look hard to see how this sort of change continued through the westward expansion, with new societies experimenting, successfully and otherwise, with new ways of living that were unimaginable by their forebears.

Now we’re in the 21st century, and apparently there are no new frontiers, or at least not on Earth. It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to find a place where no one has ever gone before. The cities are crowded, and even the countryside is getting short of elbowroom. And so society is becoming stagnant again, with a strong impulse toward authoritarianism on one hand and an equally strong tendency toward nostalgia on the other. So unless we want to slide into the decadence that marked the decline of great civilizations of the past—I just returned from a trip to Paris, where I saw evidence of this in the French royal palace in Versailles during Louis XVI’s reign—we’re going to have to seriously consider going somewhere else. And anyone who’s read my work knows what my idea of that “somewhere else” is.

Hickman: So is it fair to conclude that it ought to be humans and not just our machines in outer space?

Steele: Probes have taken farther and faster into space than people could have gone, there’s no question about that. Even the most optimistic space advocates can’t say that we would have reached Jupiter by the 1970s or Neptune by the 1990s. And we now know that there are places in the solar system where it may be too dangerous for people to go… the inner Galilean moons, for instance, or the surface of Titan. But the more rovers we send to Mars, the more our appetite gets whetted to actually go there ourselves.

At least that’s the way it is for those of us who like to put our boots on the ground. I have friends of mine—including some science fiction writers—who don’t see the purpose of this. They see the dangers of space exploration as being too high for anyone to want to risk life and limb. Well, okay, if you prefer to spend your days in front of a computer screen getting Cheetos dust on your fingers, that’s your privilege. If I could, though, I’d give anything to hike the Valles Marineris or climb Mons Olympus. I’ll probably never have that chance—unfortunately, it appears that I was born too early for this—but I want the next generation to have that opportunity. It’s not just about sightseeing, but about making humankind a spacefaring civilization, and we can’t do that by simply relying on robots.

Hickman: Earth remains politically fragmented in superstates for the next several centuries in your Coyote universe novels. There is a European Alliance, a Pacific Coalition, South Africa, India and a United Republic of America later supplanted by a Western Hemisphere Union. The UN still exists and still functions as nothing more than a talking shop. Why predict that we won’t develop a single government for Earth?

| I think we’re approaching a true Space Age that will make past efforts look like a prelude. |

Steele: I find it very difficult to believe in the old science fiction notion of the United Earth Federation or whatever else you want to call it. It’s not just the vast political differences that make this sort of unification not very likely; it’s also the vast cultural differences. Although English has become the de facto international language and McDonald’s has become the global purveyor of junk food, people in different countries want to maintain their own identities, and rightfully so. And this sort of collective individualism, so to speak, manifests itself in their chosen forms of government. France has embraced a form of democratic socialism that the United States has rejected (except when it suits us to do so; then we just call it something else). Russia has experimented with democracy, but it appears to have a tradition of authoritarianism that’s hard to shake. Theocracy in one form or another may always be the status quo for much of the Middle East. Can any one form of government resolve all these differences? I think not. The United Nations has a very worthy function as a venue for international negotiation and peacekeeping, but I don’t believe that it will ever be a one-size-fits-all legislative body. Nor has it ever meant to, really.

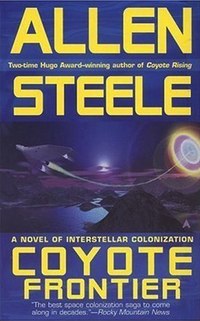

Hickman: I enjoyed the exchange about Article II of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty in your 2005 novel Coyote Frontier between a representative of the Coyote Federation, the rebel government on the terrestrial moon Coyote, and the representatives of different governments on Earth. In the end it is clear that the rebels will succeed in violating the treaty’s prohibition against claiming sovereign territory in outer space. Were you telling us something important about that provision of the treaty?

Steele: You have to remember how things stood 45 years ago when the United Nations formulated the space treaty. The US and the USSR were locked in a cold war that was not only on the perpetual verge of becoming hot, but also extending beyond Earth. Remember the scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey when we see orbital nuclear weapons? That was a real concern when that movie was made. So was the notion that the winner of the space race would not only plant its flag on the Moon, but also claim it as national territory. So the treaty has necessary to prevent an international crisis from occurring if either side decided to pursue an arms race in space, and to that degree it’s been successful. When a Russian satellite passes above us, the most lethal thing it has aboard is a camera.

Things have changed quite a bit since then. Not only has China become the third superpower to gain manned spaceflight capability, but Europe, Japan, India, and Brazil have also developed unmanned space technology, and North Korea, South Korea, Vietnam, and Indonesia are pursuing the same. Of those countries, both China and India are actively pursuing lunar exploration; for the US, returning to the Moon has been a matter of taking two steps forward then one step back for the last forty years, and that’s giving those other two countries an enormous window of opportunity. And we’re only discussing government-funded space initiatives. Space industry is something else entirely. SpaceX has no intention of settling for just being able to send cargo to the International Space Station, and neither are any of its competitors.

I think we’re approaching a true Space Age that will make past efforts look like a prelude. If that’s true, then at some point the 1967 space treaty will become obsolete. Not useless, just ill-suited for a new reality. The farther humankind ventures from Earth, the less enforceable the treaty will be; it will be as absurd as the Boston City Council trying to pass leash laws for San Francisco. This is what I was trying to point out in that scene in Coyote Frontier, and in the series as a whole. Once humankind reaches the point where we’ll have off-world colonies, Earth governments will have a lot of trouble trying to control them, for better or worse.

Hickman: Encounters with intelligent extraterrestrial species are important in the Coyote universe. How do you think they might react to the description of outer space as “the province of all mankind” in that treaty?

| We’re coming out of a period in our history in which fear and distrust were the predominant factors, and I hope (and expect) that science fiction won’t be on a war footing for very much longer. |

Steele: If the UN space treaty is even remembered by then, I doubt any extraterrestrials who become aware of it will take it seriously. Hopefully, humans won’t either. However, there will probably always be someone who considers Earth to be the center of the universe and the human race to be the crown of creation, and those people will view any contact with an alien race to be cause for alarm. I just hope that, if and when we make first contact, we’ll be mature enough not to lock and load as soon as we see the other guy.

Hickman: I hope you are right about that. The outcomes of those encounters with intelligent extraterrestrials are remarkably happy. Are you actually optimistic about how that might work out or does it just make for more interesting storytelling?

Steele: So long as those who make that first meeting aren’t paranoid, I’m optimistic for a peaceful and mutually beneficial outcome to a first contact situation. It makes sense to be cautious, of course, of course, but it would be foolish to approach an alien race with both guns blazing. This sort of mindset could trigger a conflict that could have been avoided, and the other guys may have bigger guns than we do.

I sought to depict this sort of situation in Spindrift, where a first-contact mission in interstellar space is jeopardized by a trigger-happy commanding officer who’s itching to use the nuclear weapon that’s been covertly placed aboard his vessel. One of the reasons why I wrote this particular novel is that I’m tired of the militaristic sort of space opera that says that any contact between humans and aliens will necessarily be hostile. Much of this, of course, is intended for a juvenile audience which discovered SF through movies and games, but I also believe that this is one of those occasions when SF subconsciously reflects the time in which it was written; in this case, the post-9/11 era and the wars that happened during it. We’re coming out of a period in our history in which fear and distrust were the predominant factors, and I hope (and expect) that science fiction won’t be on a war footing for very much longer.

Hickman: Like the work of Robert A. Heinlein, your work develops several themes that resonate powerfully with American readers in particular: that the exploration and settlement of frontiers is courageous rather than shameful and that religious and political extremism should be distrusted as antithetical to reason and hostile to science. Is that fair? So how comfortable are you with the comparison between your work and that of Robert A. Heinlein?

Steele: I’ve always had mixed emotions about the Heinlein comparison. It’s flattering to have my work mentioned in the same breath as one of the genre’s grand masters, but this sort of comparison can lead readers to expect the wrong things. Heinlein left footprints that are enormous; there’s no way I can stand in them easily. I have written about many of the same things as he did, so perhaps the comparison is inevitable, but while I agree with Heinlein on many issues, there are also many things he wrote with which I strongly disagree.

| Science fiction writers are constantly peering over the shoulders of scientists and technologists, and incorporating what they see into their novels and stories. But scientists are frequently inspired by science fiction as well, and thus pursue ideas that were first expressed in science fiction. |

I met Robert Heinlein very briefly when I was a teenager, but I didn’t get a chance to do much more than thank him for writing many books that I loved and accidentally step on his foot. I think that, if he and I were to meet today and sit down for a chat, our discussion would be… well, interesting. Sort of like a dinner table conversation between a conservative father and his liberal son.

Hickman: Do you have a favorite Heinlein novel? Please tell me that it’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

Steele: The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress is one of my favorites, yes, but if I had to name the one that had the most profound influence on me, it would be Time Enough For Love. This is a book that a lot of people dislike or even hate, and I’ll grant you that it can be a hard read. I bounced off it a couple of times before I understood where Heinlein was coming from, and that this isn’t a novel about SFnal ideas but instead about a man’s life. Once you get that, though, it’s a rewarding novel. I think Heinlein was trying to tell readers who’d been the kids who’d read his young-adult novels what they needed to know to live as adults, and in my case, the lesson was one that I enjoyed.

Hickman: How do you see the relationship between science fiction and science?

Steele: I see it as a feedback loop. Science fiction writers are constantly peering over the shoulders of scientists and technologists, and incorporating what they see into their novels and stories. But scientists are frequently inspired by science fiction as well, and thus pursue ideas that were first expressed in science fiction. Take, for example, Robert H. Goddard, the father of American rocketry. As a child, Goddard was inspired to pursue space flight after reading H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds; he wanted to go to Mars and see if there were any Martians there, and so he devoted his life to developing the ways and means of getting there. But Goddard quickly gave up on the idea of developing some anti-gravity machine and instead went about inventing the liquid-fuel rocket, something that almost no one else had yet considered (Konstantin Tsiolkovsky did, too, but he was working in isolation in Soviet Russia, and no one in the West knew what he was doing). The German Rocket Society was paying attention to Goddard’s work, among them Hermann Oberth and his protégé Wernher von Braun, and before they were absorbed into the Nazi war effort, their first major project was acting as technical advisers to Fritz Lang’s movie Woman in the Moon, the movie where, for the first time, the countdown was introduced as a dramatic device, but which later became a necessary element of rocket launches. This sort of back-and-forth exchange lies at the heart of science fiction, and that’s what makes it not only interesting, but also vital. One drives the other, I think. I hope I’m making a lasting contribution to both.