Between the darkness and the lightby Dwayne A. Day

|

| “I was very anxious to get the military involved in the shuttle because it was in fact the most capable launch vehicle that we were building at the time,” Mark told the NRO historian. |

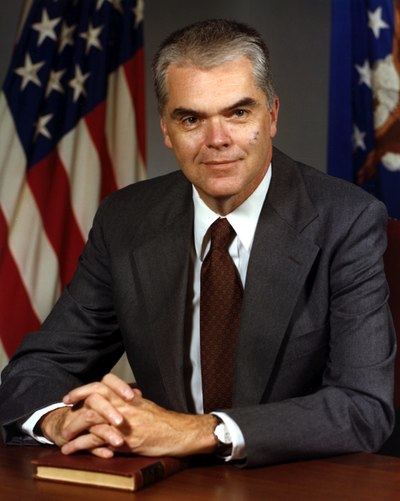

A newly declassified interview with Mark, performed by NRO Historian Gerald Haines in March 1997, sheds new light on his tenure at the NRO and his decisions about major programs then underway, particularly their relationship with the shuttle. Although some portions of the interview are deleted, it is not difficult to determine what he was speaking about since much of the story has appeared in previous books, notably a 2001 history of the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology written by Jeffrey Richelson, The Wizards of Langley. Mark also wrote a 1987 memoir. At that time he was not allowed to discuss satellite reconnaissance because even the name of the NRO was classified. However, Mark wrote in his book that he was a strong advocate of the shuttle. This new interview makes it clear what that meant.

One of the decisions that Mark was involved with was whether to adapt the NRO’s existing real-time imagery satellite, the KH-11 KENNEN, then managed by the CIA, to also have a radar capability. The alternative was to develop a standalone radar satellite. Mark claims that he was in favor of merging the missions because it would have been cheaper, but he suggested to the Air Force segment of the NRO, then known as “Program A,” that they take advantage of equipment then being developed in NASA. He viewed this as a way of building the standalone satellite cheaper. Although the segments about the NASA technology are deleted, what NASA was developing was a spacecraft bus that could be used to support various payloads. “So one system would gain economic advantage through commonality on the spacecraft, and the other one would be commonality with NASA,” Mark explained.

Mark said that he was leaning toward combining the two capabilities even though it would have required launching more satellites. However, he was convinced that separating them was the better approach after a conversation he had with Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, who told him that giving the radar imaging mission to the Air Force component of the NRO would be better politically. It would keep the Air Force involved in the development of NRO payloads and maintain the healthy competition between the CIA and the Air Force that drove the production of better and more capable systems.

| Mark said that some within the NRO wanted to build a spacecraft—most likely a sensitive eavesdropping satellite for operating in geosynchronous orbit—to fit aboard the smaller Titan 34D rocket. Mark thought that was unwise. |

But perhaps the most significant aspect of his tenure at the NRO involved the Space Shuttle. “I was very anxious to get the military involved in the shuttle because it was in fact the most capable launch vehicle that we were building at the time,” Mark told the NRO historian. “The things that we have done since then, you know, repair on orbit, and check out on orbit before you deploy a satellite and all that stuff with human beings I thought was a very valuable capability to have. My military friends don’t agree with that to this day.”

Although deletions in the transcript make it a little difficult to understand exactly what he is referring to, the interview sheds a little more light on an episode that Mark had hinted at in his memoir. Mark said that some within the NRO wanted to build a spacecraft—most likely a sensitive eavesdropping satellite for operating in geosynchronous orbit—to fit aboard the smaller Titan 34D rocket. Mark thought that was unwise. “We would have had to compromise our capability if we had to fit those things into the existing launch vehicles.” According to Mark, the issue was volume, not mass, and apparently involved equipping the satellites with a large deployable antenna.

So Mark forced the designers to increase the size of the spacecraft. Haines, interviewing Mark, suggested that the redesign drove the costs of the spacecraft higher. “That’s certainly true,” Mark conceded. “But had they designed the goddamn things for the shuttle in the first place, it was their fault that they had to redesign it. Because they said ‘we’ll never go on the shuttle,’ and so when I got there I said ‘sorry fellas, that’s crazy. You deliberately compromised capability that you could have, because for reasons I don’t understand you don’t want to use this launch vehicle. That is how things evolve.’” Although he does not state this in the article, two of the massive eavesdropping satellites were deployed during two mid-1980s shuttle missions.

The shuttle was also running into cost and schedule problems, and if it was canceled, then the larger spacecraft could not be launched. So Mark persuaded Harold Brown to persuade President Carter to save the shuttle program. Later, Mark was succeeded at the NRO by Edward “Pete” Aldridge, who reversed his policy regarding the shuttle, purchasing more expendable rockets and not requiring that spacecraft be designed for shuttle-only launch. Marks characterized this as Aldridge lacking the political power to maintain the relationship, but Aldridge has indicated that he made the split because he thought it was the right thing to do. Old-timers in the NRO hail Aldridge’s decision and think that Mark’s forced marriage of NRO payloads and the shuttle was a mistake.

| Old-timers in the NRO hail Aldridge’s decision and think that Mark’s forced marriage of NRO payloads and the shuttle was a mistake. |

The interview sheds additional light on the NRO of the time. According to Mark, there was an agreement between the White House and Congress that “as long as the budget of the NRO stayed below a billion dollars, no testimony, no questions, just go right through.” Mark remembered that the NRO budget finally exceeded a billion dollars in fiscal 1978, a time when NASA’s budget was $4.164 billion.

Mark also said that he advocated declassifying the existence of the NRO and its basic activities, while maintaining secrecy concerning its technical capabilities. He thought that it would help bolster arms control by being able to tell the American public that the United States had a robust capability to monitor the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. But whereas arms control was a major interest for President Carter, it quickly faded under Reagan. Although Mark was a Democrat, he admired Reagan, whom he had met in the early 1970s when Mark was running NASA Ames and Reagan was governor of California. NASA had used its U-2 aircraft to monitor California wildfires, a capability that had impressed Reagan greatly.

The interview makes it possible to better understand the still foggy relationship between the Space Shuttle and the national security payloads that ultimately flew on it. Mark was an unashamed advocate for closer cooperation between the white and the black space programs, a relationship that was always fraught with challenges.