Review: The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smilingby Jeff Foust

|

| “Unlike most mortals, Yuri Gagarin was born twice,” Jenks remarks. There was his original, physical birth in 1934, and his second “birth” as a public figure in 1961. |

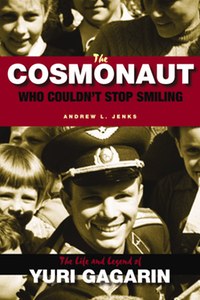

Gagarin’s life, of course, has been the subject of a number of biographies, ranging from the hagiographic to the sensationalist (see “Review: Starman”, The Space Review, April 18, 2011). The latest to examine Gagarin before and after his historic flight is The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling, by Andrew Jenks, a historian at Cal State Long Beach. His account, though, is not just a simple examination of Gagarin’s life, but a more complex analysis of mythology versus reality, and how perceptions of Gagarin have changed over time.

Jenks does devote much of the book to a biography of Gagarin, tracing his rise from obscurity in rural Russia—including a time as a child when his family’s farm was in territory occupied by the Nazis—through his education and training as a military pilot to his selection as a cosmonaut and flight on Vostok in April 1961. The impression Jenks leaves of Gagarin is that of someone compensating for his rural origins and limited formal education through determination, as well as a gregarious, outgoing personality and willingness to volunteer that won the attention and admiration of teachers and classmates alike. It’s less clear, though, what was motivating him: was he pursuing a career in aviation that dates back to a chance encounter with a downed Soviet pilot during the war, or was his seeking escape from a life in the provinces or a father than often disapproved of him?

Once he made his sole orbit of the Earth and became a national hero, his life changed—even his past. “Unlike most mortals, Yuri Gagarin was born twice,” Jenks remarks. There was his original, physical birth in 1934, and his second “birth” as a public figure in 1961. That meant even before he returned to Earth “the Soviet mythmaking machine began crafting the story of Gagarin’s early life,” where his humble origins could be emphasized as an ideal Soviet man, while other, less desirable details could be glossed over and ignored. Gagarin, the book recounts, appeared willing to go along with this and become, in effect, a leading spokesman for the Soviet Union during his travels within the country and around the world.

Jenks goes beyond the life of Gagarin, through his death in a fighter crash in 1968, to examine some deeper issues. One is the clash between “sacred and profane realities”: that is, between the myths of Gagarin’s life and the actual details, including those imperfections that the Soviet propaganda apparatus would ignore. Gagarin’s rise to prominence came in an era of Soviet history that embraced sincerity, at least when compared to the Stalin regime, and Gagarin, as a good communist, made the public case that there should be no reason to lie. Yet, Gagarin had to lie, in order to prevent the sacred reality of his life and mission from clashing with the more profane details (for example, the Soviets insisted that he landed in his capsule at the target landing zone; in fact, he ejected from his capsule and landed separately from it, both hundreds of kilometers from the intended target.) Did the stress of that, Jenks wonders, drive Gagarin to drink in the years after his flight?

| The book is not a complete biography of Gagarin, and Jenks suggests that a truly authoritative account of his life may not be possible, given than may historical records have either been destroyed or are inaccessible to researchers. |

Jenks also examines how the perceptions of Gagarin in the Soviet Union and Russia changed over time. He was, of course, revered as a hero after his flight (although, Jenks notes, some veterans of the Great Patriotic War grumbled about his double promotion from lieutenant to major immediately after his flight). After his death, though, and particularly by the 1990s, his standing waned, given stories of his drinking and alleged affairs. More recently, though, his reputation has been rehabilitated, becoming a “cosmic, karate-chopping Vladimir Putin.” This was especially true outside Moscow: visiting the Russian capital in 2007, Jenks found the grand Cosmonaut Pavilion there turned into a flea market, with monuments outside littered with graffiti. But in the southern city of Saratov, where Gagarin went to technical school and near where he landed, he found a “meticulous maintenance of the cult” where Gagarin was still held in the highest of esteem.

The Cosmonaut Who Couldn’t Stop Smiling is not a complete biography of Gagarin, and Jenks suggests that a truly authoritative account of his life may not be possible, given that many historical records have either been destroyed or are inaccessible to researchers (Jenks notes that he was rejected when he tried to access the archives at Star City, the cosmonaut training facility.) “The process of bronzing a person and turning him or her into an idol therefore seems to be a one-way affair: the individual can be turned into an icon but never back again into a living, breathing human being,” he concludes. What is left, then, is what Jenks has done here: examine what we do know about someone as famous as Gagarin and how the perceptions of that man-turned-icon have changed over the years.