Review: Europe to the Starsby Jeff Foust

|

| Even as ESO was finishing a relatively large telescope in the mid-1970s, astronomers were thinking even bigger. |

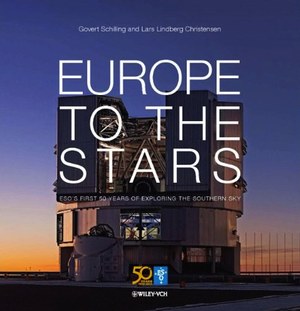

Europe to the Stars was commissioned by ESO as part of commemorations of the organization’s 50th anniversary last year. Several factors drove representatives of five nations—Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Sweden, and West Germany—to establish ESO in 1962. Astronomers sought, as they have since the invention of the telescope, bigger instruments for peering into the night sky; they were also motivated to build these telescopes in the Southern Hemisphere, whose skies were relatively unexplored compared to those in the North. European governments, meanwhile were motivated to work together by the growing expense of such large telescopes that made them largely unaffordable to individual nations in postwar Europe.

European astronomers were originally interested in South Africa, having established a series of observatories there since the 19th century. Only after ESO was founded did they consider Chile, whose dark, clear skies started to attract interest from astronomers in the 1950s and early ’60s. American astronomers were scouting sites there for what would become the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, and there were discussions about cooperation with ESO, but ultimately the Europeans decided to go on their own, apparently because they preferred to negotiate directly with the Chilean government, while the Americans were working with Chilean universities. ESO selected a mountaintop site called La Silla and started building a series of telescopes there, the first opening in 1969. That site’s centerpiece, a 3.6-meter telescope, opened in 1976.

Even as ESO was finishing that relatively large telescope, astronomers were thinking even bigger: a telescope with an effective aperture of 16 meters, a concept called descriptively, if unimaginatively, the VLT. ESO settled on a concept of building four 8-meter telescopes with the same light-collecting power of a single 16-meter telescope, but which would be more feasible to build than a monolithic mirror. (Moreover, the telescopes could be used individually for those observations that didn’t require the power of the four combined.) In the 1980s, ESO built the New Technology Telescope at La Silla that demonstrated some of the key technologies needed for the VLT, including the use of adaptive optics to control the shape of the mirror, allowing for thinner, lighter mirrors. In 1999, ESO inaugurated the VLT, located at Paranal, a mountain several hundred kilometers north of La Silla.

ESO has since moved on to even more ambitious telescopes, as astronomers continue to demand more photons and better resolution across the electromagnetic spectrum. ESO is cooperating with the United States and Japan on the development of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a cluster of radio telescopes in northern Chile nearly full operation. ESO is also in the planning stages of a giant optical telescope nearly 40 meters in diameter, called the European Extremely Large Telescope, or E-ELT. (The E-ELT is a scaled-down version of a proposed telescope 100 meters across called the OverWhelmingly Large Telescope, or OWL.) This telescope, with a projected cost of more than one billion euros (US$1.35 billion), is slated to open in the early 2020s.

| While ESO may be obscure to many outside Europe, it’s clear that its facilities make it one of the world’s leading astronomical institutions. |

Europe to the Stars is a glossy overview of ESO’s history and science in two respects. The large-format book is lavishly illustrated with many color images of both the telescopes and the astronomical phenomena those telescopes have observed. The text also does a fine job examining the development of ESO and the science its telescopes have supported, as well as interviews with several former directors-general of ESO. The book is glossy in another respect, too, though: it suggests an uninterrupted, inevitable rise of ESO, glossing over any problems along the way. The book does briefly mention some technical setbacks, like a 2.6-meter mirror for a survey telescope that was completely shattered in transport to Chile. But surely there have been programmatic and organizational issues as well, particularly as ESO has grown in both the number of telescopes and member nations (now 14, with the 15th and first non-European nation, Brazil, awaiting ratification by its government of the agreement to join.)

While Europe to the Stars might not peer deeply into the details, good and bad, of ESO’s half-century history, the book—accompanied by an hour-long documentary in the included DVD—offers a fine, well-illustrated overview of the organization and its accomplishments. While ESO may be obscure to many outside Europe, particularly those who don’t follow astronomy closely, it’s clear that its facilities today, and those planned for the future, make it one of the world’s leading astronomical institutions.