Review: Spacewalkerby Jeff Foust

|

| “I was going to Purdue University, I was going to become an engineer, and I was going to work in our country’s space program. I made it my life’s goal.” |

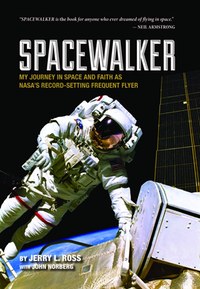

Perhaps the best example of this is Jerry Ross. While never well known outside the space industry, Ross built up an impressive career as a NASA astronaut. His time in the astronaut corps spanned the entire flight history of the Space Shuttle program: NASA selected him in 1980, a year before STS-1, and he retired early last year, about six months after the final shuttle flight, STS-135. Over more than three decades, Ross flew on seven shuttle missions, a record he shares with Franklin Chang-Diaz, and performed nine spacewalks totaling 58 hours, third among all spacewalkers worldwide.

As he recounts in his autobiography Spacewalker, his interest in spaceflight dates back to growing up in rural northwestern Indiana in the 1950s and ’60s, as the Space Age started. “To be honest, in fourth grade I didn’t really know for sure what an engineer did,” he recalled, but knew it was engineers who were working on the space program. “I was going to Purdue University, I was going to become an engineer, and I was going to work in our country’s space program. I made it my life’s goal.”

A theme of that book was that realizing that goal—which later expanded to becoming an astronaut—required dealing with obstacles and setbacks along the way. In hindsight, he saw those setbacks as opportunities. His plan to become a jet pilot was derailed by an Air Force ophthalmologist who determined that Ross would one day need glasses and thus could not be a pilot. Ross trained as an engineer, and found his way to the Air Force’s Test Pilot School as a flight test engineer, but had to turn down his original acceptance to fulfill a commitment to his commanding officer at the time at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. His first application to join the astronaut corps, in 1978, was rejected, but he was instead offered the opportunity to come to NASA to work on military payloads planned for shuttle missions, putting him on the inside track the next time he applied, in 1980.

Much of the book is a straightforward retelling of his life before and after becoming an astronaut, including recounting each of the seven shuttle missions he flew on from 1985 through 2002. Spliced into the book are passages written by his wife and two children, as well as a childhood friend, offering their perspectives on Ross and his achievements. Spacewalker is not a tell-all memoir by any account, but instead a chance to tell his story of how he realized a childhood dream thanks to hard work and, as the book’s subtitle suggests, his faith in God.

| “I feel blessed to have served our country in such a unique and exciting way,” he writes. “I was fortunate to be able to live a relatively normal life while having the opportunity to fly in space.” |

The one area where Spacewalker has a bit of an edge is near the end, where Ross discusses the future. “I am very upset with the current direction, or more appropriately, the lack of direction of the US space program,” he writes. He supported the Constellation program, while acknowledging that the White House and Congress didn’t sufficiently fund it. The cancellation of Constellation in 2010 and its replacement by a policy that includes development of commercial crew transportation systems doesn’t sit well with him. “Forces at work inside NASA are dismantling much of the human spaceflight capabilities we used to have,” he claims, without identifying who those “forces” are. “These forces are trying to push commercial spaceflight as far and as fast as they can, at the expense of and in place of NASA’s own programs.”

Ross says that, thanks to Congress, at least some elements of NASA’s human spaceflight capabilities are “on life support until NASA management changes.” NASA’s current management, though, is led by a former astronaut, Charles Bolden, who was in the same astronaut class as Ross. “Charlie is a good person, and he had a brilliant career,” he writes. “But we don’t agree on what is happening at NASA.”

Fortunately, Spacewalker doesn’t end on that pessimistic note. “I feel blessed to have served our country in such a unique and exciting way,” he writes in the book’s final chapter, content with realizing his goals he set as a child, even if he didn’t get the media attention of earlier astronauts. “I was fortunate to be able to live a relatively normal life while having the opportunity to fly in space.” That’s a pretty good achievement, at least until the day when flying into space can be considered part of a normal life.