A Martian adventure for inspiration, not commercializationby Jeff Foust

|

| “We need to do something innovative and exciting,” Tito said at a press conference in Washington announcing his foundation’s plans. |

But even with that experience, MacCallum says he was taken by surprise by the company’s latest project. “If someone had told me six months ago I’d be talking with you about this,” Taber MacCallum said in an interview last week, shaking his head as the words trailed off. The “this” he was referring was the plan formally unveiled February 27 by a new organization, the Inspiration Mars Foundation, to mount a privately-funded crewed Mars flyby mission in 2018. Yet he and others were not just talking about, but also actively working on, something that sounded like science fiction but which they had, at least so far, not proven could not be done.

The last couple of years have seen the rise of a number of audacious private space ventures: giant air-launched rockets, asteroid mining efforts, and private human lunar landing missions. Yet Inspiration Mars stands out from the others not just in what they’re planning to do, but how they’re planning to do it: a one-time, non-commercial project with a firm deadline dictated by orbital mechanics, and with the goal not of making money but inspiring a new generation.

From the Earth to Mars and back in 501 days

At the heart of Inspiration Mars is its founder and initial funder, Dennis Tito. The wealthy investor is best known in space circles for his groundbreaking—and, at the time, controversial—flight to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2001 as the first space tourist. That was not, though, his first experience with space. Prior to his business career he worked at JPL, developing trajectories for Mariner missions to Mars in the 1960s.

About a year and a half ago, he decided to dust off those old skills to see if there was a way a private effort could help reinvigorate human spaceflight. “We need to do something innovative and exciting,” he said at a press conference in Washington announcing his foundation’s plans. “We need to bridge the gap between the current ISS flight and the SLS/Orion, which is our planned architecture for future deep space flight.” Such “stepping-stone” missons, he said, could gain engineering, life science, and other experience needed for eventual human missions to land on Mars.

Tito said he was initially looking at missions in the vicinity of the Moon, including trajectories that took missions out beyond the Moon and back. He then stumbled upon a 1996 paper that examined Earth-Mars “free return” trajectories, which allow a spacecraft launched from Earth to fly by Mars and return to Earth without any maneuvers after the initial trans-Mars injection burn. That paper found pairs of such trajectories, repeating every 15 years, which are much faster than the rest: round trips of about 1.4 years versus two years or more. Tito called these trajectories the “low-hanging fruit” of human Mars mission architectures.

The particular opportunity Tito is targeting is in 2018 (there is an earlier one in late 2015, but that is too ambitious even for this effort.) In the trajectory Tito and others developed, a spacecraft would launch from Earth on January 5, 2018. On August 20, it would fly past Mars at a distance of little as 100 kilometers. The spacecraft would then go back inside the Earth’s orbit, traveling nearly as close to the Sun as Venus (although not near the planet itself) before returning to Earth on May 21, 2019. The total flight time: 501 days.

Developing a trajectory, however, is only the first step towards determining if a mission is feasible. Could a crewed spacecraft actually be launched on such a trajectory and keep its occupants alive for the 501-day journey? Last September, MacCallum recalled, Tito contacted Paragon to ask them to study this. “We were characteristically skeptical, and we tried to talk him out of it,” he said at the press conference, but Tito convinced them to see if it could be done.

That study, he said in an interview the day before the press conference, found no issues that would prevent a mission. “We kept on finding issues and then finding a workaround,” he said. “We all went into this very skeptical… but it all sort of kept working out.”

One issue they looked at was the size of the crew. A two-person crew, MacCallum said, would offer a “huge safety benefit” over sending a single person; a three-person crew, he said, offered less of an additional safety benefit while introducing “psychological issues” as well as increased life support requirements.

| “This is going to be the Apollo 8 moment for our next generation,” said Jonathan Clark. |

Once it appeared a two-person crew would be ideal for the mission, they concluded the crew should be a man and a woman; ideally, a married couple beyond childbearing age. “The idea that we have a man and a woman going on this mission is an important idea,” said Jane Poynter, the president of Paragon. She said her experience being part of the original Biosphere 2 crew with MacCallum (now her husband) demonstrated the importance of having a “trusted, tested couple” who can remain productive over a long journey.

“It’s also important that this is a man and a woman because they represent humanity,” she added, saying that such a crew could be inspirational to all children. “Whether they’re a girl or a boy, they see themselves reflected in that crew. And that is, after all, what makes this mission all worthwhile.”

That comment, and the foundation’s name itself, hints at the central rationale for this mission. While it may demonstrate technologies and provide scientific insights for long-duration spaceflight, Tito and others involved hope that it be an inspiration to a new generation, particularly to pursue science and engineering careers, in much the same way as Apollo inspired an earlier generation. “This is going to be the Apollo 8 moment for our next generation,” said Jonathan Clark, associate professor of neurology and space medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, who is working with Inspiration Mars on space medicine issues for the mission.

Such a mission, MacCallum said in an interview, would push against the perception that American society is too risk-averse. “I’ve heard a lot of times people saying, ‘This is the type of thing that America used to be able to do,’” he said. “We could get America back to taking those kinds of risks that really push the boundaries and inspire people to greatness.”

Dennis Tito, speaking at a February 27 press conference in Washington, has committed to funding the first two years of this project while raising the rest of the money needed through donations and media rights. (credit: J. Foust) |

Risks and challenges

Needless to say, launching a human Mars flyby mission in less than five years carries with it plenty of challenges that have to be overcome. One of the most obvious ones is developing the mission architecture itself: the combination of launch vehicles and spacecraft that can carry out this expedition.

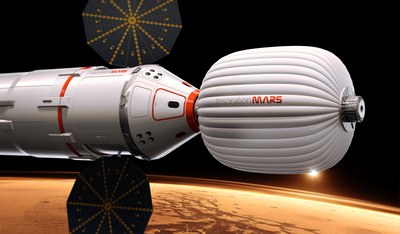

The foundation does have one such mission architecture, outlined in a paper Tito was scheduled to give Sunday night at the IEEE Aerospace Conference in Big Sky, Montana. That approach uses a single Falcon Heavy launch vehicle, currently under development by SpaceX, launching a crewed Dragon spacecraft, also from SpaceX. That concept would be capable of supporting a two-person crew for the 501-day mission using “state of the art” life support technologies.

The use of SpaceX vehicles, though, doesn’t mean that the company is part of the Inspiration Mars team, or has even been in serious discussions with the company. At the press conference, MacCallum said they had contacted SpaceX only to confirm that the published data on their vehicles is accurate. (A report in the Wall Street Journal, citing unnamed “industry officials,” claimed that talks between Inspiration Mars and SpaceX had taken place but “imploded” in recent weeks.)

Speaking at a NASA press conference about the company’s next commercial cargo mission to the ISS the day after the Inspiration Mars announcement, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell confirmed that the company hadn’t been in discussions with the foundation, at least not yet. “I think his plan is very ambitious,” she said. “If he can come up with the funding to execute this mission, I’d be happy to have him as a customer.”

MacCallum said in last week’s interview that the company was looking at multiple options to carry out the mission. “It’s an open field. We’re looking at two, maybe three, scenarios that look very promising,” he said, including some that use multiple launches. “We actually feeling a lot better about launch than we were earlier on.”

One reason for that optimism, he said, is the diversity of options available to them for putting together such a mission. “It’s an interesting time to be doing a mission like this, because there are more spacecraft in development now than the entire history of American spacefaring up to this era,” he said, a reference to the multiple commercial crew vehicles under development as well as NASA’s Orion spacecraft. “We have this huge range of puzzle pieces that we can put this mission together from.”

Another challenge is keeping the crew in good health, physically and emotionally, during this mission. Clark noted that they already have plenty of experience dealing with the effects of microgravity. “Deep space is another matter. We’re not protected by the magnetic fields around the Earth, so we’re going to have to contend the issues of radiation,” Clark said. “That’s where I hope to harness the powers of the academic community.”

He said they were open to “novel approaches” to dealing with the radiation issue, leveraging developments in personalized medicine and genomics. “Do we have our work cut out for us? Yes, absolutely,” he said. “Radiation is certainly a concern, but it’s not an absolute showstopper.”

| “We have this huge range of puzzle pieces that we can put this mission together from,” MacCallum said of designing this mission. |

And what will that two-person crew do during the mission? “Mostly keeping themselves alive,” MacCallum said. The spacecraft’s life support system will be “as non-automated as possible” so it is more easily maintained by the crew, a very different approach to the more automated systems on the ISS designed to free up crew time to do science, but which are more difficult for crews to repair without getting replacement items sent up form Earth. “It’s going to be a ’55 Chevy. They’re going to be taking this apart a lot,” he said. There will be time for research, including a set of human deep space physiology experiments being developed by Clark, as well as educational outreach activities.

MacCallum said that the foundation is creating an advisory and review board to support the project; that board will be chaired by Joe Rothenberg, a former associate administrator for spaceflight at NASA. Rothenberg, MacCallum said, believes that this mission is “conceptually feasible” but that the project has a lot of work ahead of them to actually implement it. He added that even before the foundation went public with its plans, people from various fields “were coming out of the woodwork” to offer support for the mission, or volunteer to be on the crew.

Any mission like this, though, carries with it the ultimate risk: the death of the crew. “We have a plan we’re working on” to address the potential death of one or both crew members on the mission, said Clark, who has a particularly intimate insight into this issue: his wife, Laurel, died on Columbia a decade ago. “Life is risky, and anything that is worth it is worth putting it all at stake for.”

June Scobee Rogers, who lost her first husband, Dick Scobee, on Challenger, expressed a similar sentiment. “After the Challenger accident, I was asked that question many times,” she said, regarding whether the risk of human spaceflight was worth it. “And my response was always that without risk, there is no knowledge.”

Tito played down any perception that the foundation would be taking any major risks with the crew. “I would not be comfortable launching this mission with anything other than a .99 probability of the crew returning safely,” he said.

An adventure, not a venture

Another obvious challenge is a financial one: paying for a mission like this. Tito and others involved with the project were reticent to put a price tag on the mission, in part because the mission architecture has yet to be developed. In last week’s interview, MacCallum said it would cost “a fraction of Curiosity,” the NASA Mars rover whose estimated mission cost is $2.5 billion. At Wednesday’s press conference, Tito estimated it would cost “a factor of 100” less than previous concepts for human Mars landing missions or even the Apollo program. “This is really chump change compared to what we heard before about Mars.”

| “Let me guarantee you: I will come out a lot poorer as a result of this mission,” said Tito. “But my grandchildren will come out a lot wealthier from the inspiration that this will give them.” |

Tito said he would fund the first two years of development of the mission concept with his own money, although, like the overall price tag, he declined to disclose how much that would be. He acknowledged, though, that the bulk of the costs would come after that two-year period, when the launch vehicle, spacecraft, and other key components are purchased. It is enough, though, to allow the team to focus on developing the mission without worrying about money. “It’s tremendous,” said MacCallum, to have that kind of initial backing so “you’re not worried next month whether the money’s going to keep coming in.”

While Tito is wealthy, he is not wealthy enough to fund the entire mission on his own. He said he will work to raise the rest of the money needed to carry out the mission. And it’s there where the differences between Inspiration Mars and many of the other recently announced major space ventures become clear. While those other efforts are set up as commercial ventures, making a profit and providing (eventually) a return for its investors, Inspiration Mars is taking a different approach.

“This is not a commercial mission,” Tito said. “This is not mission that, if it’s successful, I’m going to come out to be a lot wealthier. Let me guarantee you: I will come out a lot poorer as a result of this mission. But my grandchildren will come out a lot wealthier from the inspiration that this will give them.”

Tito said some of the funding could come from the sales of sponsorships and media rights: “I can imagine Dr. Phil talking to this couple and solving their marital problems,” he joked. He also said they would be open to selling data collected during the mission to NASA, although he added that was the only funding of any kind they were seeking from the space agency for this mission. Finally, they would also seek donations, from both individuals and charitable foundations.

While raising money has been a major challenge for many NewSpace ventures, Tito didn’t think it would be that big a hurdle. “I think it’s such a great mission I’m very excited about going out there and raising that money,” he said. “I don’t think it’s going to be a real difficult problem, although I’m going to assume I’ll spend a lot of my time doing that.” He noted the California Science Center is currently raising money to build a new wing to host the Space Shuttle Endeavour, and that the person responsible for raising those efforts is a friend of his. “I know his experience in raising money. It wasn’t that difficult. If you have a good idea you can raise money for it.”

The effort is driven by an unyielding schedule, thanks to orbital mechanics: after 2018 the next opportunity for a similar trajectory isn’t until 2031. “Who wants to wait until 2031, because by that time we might have company?” Tito said. He played up the patriotic angle of this proposed mission (which the foundation has dubbed a “Mission for America”), although he and others said they would be willing to purchase components from other nations. If they waited until 2031, “we better have our crew trained to recognize other flags, because they’re going to be flying out there as well.”

This mission is a one-shot effort; once the mission is over, MacCallum said, they plan to contribute the technologies developed and other data collected. “It’s a philanthropic mission,” he said. “It really is a contribution for America.” That approach, he said, helped in discussions with NASA, including speeding the signing of a reimbursable Space Act Agreement to support work on the thermal protection system the spacecraft will need to survive the high reentry velocities of such a mission. He said the project has also gotten a “very positive” reception in briefings with key Congressional committees as well as with the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy.

After the press conference, Tito was asked why he preferred spending his money on Inspiration Mars than investing it into any number of other commercial space ventures that could lower launch costs or enable new markets, and also provide a monetary return. “It’s not a better investment of money,” he said. He explained he had reached a point in his life where he was less concerned about making more money than trying to give something back.

So, is this project his grandchildren’s inheritance? “Exactly.”