Addressing the challenges of space debris, part 3: policyby Michael J. Listner

|

| Methodologies and instrumentation used to remove space debris from orbit could also be used to deorbit a vital functioning satellite belonging to another nation. Thus, a legitimate debris removal methodology might be rejected politically because it could potentially be used as a weapon. |

The second installment of this series dealt with the issue of liability both in the in the context of liability for existing space debris and liability for remediation of space debris (see “Addressing the challenges of space debris, part 2: liability”, The Space Review, December 17, 2012). Particularly, this installment noted that under current international space law, the states to whom space objects belong in orbit that are classified as space debris retain liability, and this potential legal and financial liability is an impediment to encouraging remediation activities. Morover, the potential liability surrounding remediation efforts is also a barrier to performing removal activities. As a solution, this installment posited that a general release of liability be granted for the existing body of identified space debris, and that limited liability for remediation activities be applied, both of which will have the effect of encouraging debris removal.

The final installment of this series will deal with what I see as the third significant challenge surrounding space debris removal, specifically political issues surrounding debris remediation.

Space weapons and space debris

The primary policy issue surrounding space debris remediation is the space weapons debate. The focus of this article is not to discuss the validity of the space weapons debate in so much as it is to discuss the current debate in the context of remediation activities. Since the days of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) in the Reagan years, the issue of space weapons has been a prominent issue for Russia, its predecessor the Soviet Union, and China. That contention has led to a prolific soft-power effort by both of these nations through the Conference of Disarmament with instruments such as PAROS and the PPWT, which have the stated goal of banning “space weapons.” Neither of these measures has gained much traction with the United States and its allies, but the topic has given both Russia and China a significant soft power advantage in the United Nations, especially among the non-spacefaring nations.

The crux of this is that methodologies and instrumentation used to remove space debris from orbit could also be used to deorbit a vital functioning satellite belonging to another nation, or provide a test bed for a future anti-satellite weapon that would be deployed in the event of pending hostilities. These so-called “break-out” weapons are designed to be held in reserve until needed and then launched when necessary, which provides a hurdle to verification. Thus, a legitimate debris removal methodology might be rejected politically because it could potentially be used as a weapon, and with Russia and China continually pushing the PPWT in the United Nations, the claim will doubtless be raised in the event that someone makes an effort to demonstrate a remediation methodology. However, the soft power juggernaut pushing against the idea of space debris remediation can be overcome through some bold policy initiatives both diplomatically and through the creation of customary international law.

Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty

One tactic for eroding the soft power stranglehold over space debris remediation is to utilize Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty. Article IX imposes a general duty to perform space activities in a manner that does not contaminate the outer space environment or otherwise interfere with the outer space activities of other States. Article IX also imposes a two-prong duty upon states regarding consultations. First, if any outer space activity by a state or those under its jurisdiction is planned that might contaminate the outer space environment or otherwise interfere with the outer space activities of another state, the state must undertake consultations before commencing those activities. Second, if a state believes that another state will undertake activities that may contaminate the outer space activities or interfere with the activities of another state, it may request consultations regarding those activities. The difference between the two-prong consultation rule is that one imposes an absolute duty while the other a discretionary duty.

Article IX has never been invoked and there has been little, if any, customary interpretation of how it is to be applied. However, the United States and the Soviet Union may have unwittingly created a customary precedent for when it need not be invoked during the Cold War regarding tests of anti-satellite (ASATs) in low Earth orbit. It is this precedent that might explain China’s claim that its ASAT test against FY-1C in 2007 was in accordance with international law. Furthermore, the United States and other Western nations likely missed an opportunity to invoke the second prong of Article IX consultations when it failed to request consultations with China about the FY-1C test prior to it being informed. Western intelligence agencies were aware of at least two attempts prior to the successful test in 2007 and were doubtless aware that the test that destroyed FY-1C was pending. It is uncertain why the consultation provision of Article IX was not invoked, but, in choosing not to exercise the discretional duty, it may have created a customary norm within itself.

The root of the issue of Article IX is that it lacks legal interpretation and, while customary practices of the major spacefaring nations may have created a legal conundrum about the creation of space debris, Article IX could be applied in such a way to counter soft-power maneuvering and make space debris remediation activities more politically palatable. For instance, the United States, as part of a plan to perform remediation activities, may take the bold step of invoking the first prong of the consultation requirement of Article IX in anticipation of a space debris removal demonstration, given that space remediation activities will be potentially hazardous and may create additional contamination that may interfere with the use of outer space by other states.

| The Swiss may be poised to blaze a trail for an eventual rule of customary international law with the demonstration of their CleanSpace One spacecraft. |

Invoking Article IX would not completely silence the soft power efforts of Russia and China in the UN in of itself. Doubtless, many would claim that a demonstration of space debris removal could be easily be a disguised space weapon test and might even see this as an opportunity to push the PPWT in order to verify that it is not. Such a tactic could be easily sidestepped since the PPWT’s major flaw is that it is difficult to verify. However, a good faith effort to invoke Article IX and introduce a customary norm would create a legal precedent for any future remediation activities by any state, which might put a dent in the actual covert testing of a dedicated space weapon. However, while this political tactic might partially silence the space weapons debate, it will not completely mute it. To do so, a customary rule of international law would have to be created that allows for the physical removal of space debris, but the creation of such a norm will not come about without the initiative of one of the smaller spacefaring nations.

Creation of a customary norm for space debris removal

The removal and return to Earth of a space object already has some legal precedent. In February 1984, the commercial satellite Palapa B2 was launched for the Indonesian government on STS-41B, but it failed to reach geosynchronous orbit due to a malfunction of its perigee motor stage. While the satellite was circling the earth in a useless orbit, Sattel Technologies of California purchased it from the insurance group that covered the loss. Sattel subsequently contracted with NASA to retrieve the satellite, which it did in 1984.

Sattel contracted with Hughes Aircraft Company, which originally manufactured the satellite, and McDonnell Douglas, which was the launch service provider, to refurbish and re-launch the satellite. The satellite, which was renamed Palapa B2-R, was successfully re-launched in April 1990. After the re-launch title of the satellite was transferred back to Indonesia.

Arguably, under the definition of space debris proffered in the first part of this series, Palapa B2 would not meet the definition of space debris because it had continuing economic value to the launching state, which it was able to eventually utilize. However, the physical removal of the satellite did set a precedent of sorts for the recovery of a space object belonging to another state with the explicit permission of launching state. While not setting a legal precedent for space debris removal per se, it could form the basis of customary rule of salvage in outer space.

However, to break through the soft power stranglehold in the UN, an actual demonstration of removing space debris is necessary, and one that can be performed without objection. The United States, being at the center of this tempest, would not be in a position to perform such a demonstration without substantial political repercussions. However, the Swiss may be poised to blaze a trail for an eventual rule of customary international law with the demonstration of their CleanSpace One spacecraft.

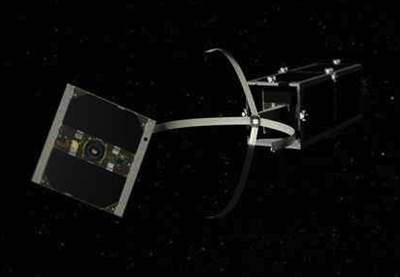

The Swiss Space Center at the Swiss Federal Institute for Technology in Lausanne announced last year that it plans to develop and launch a satellite to remove space debris from low Earth orbit. The $11-million satellite, called CleanSpace One, is intended to actively intercept and de-orbit one of two Swiss satellites: the Swisscube-1 picosatellite, launched in 2009; or its cousin TIsat-1, launched in 2010. Both are CubeSats 10 centimeters on a side. CleanSpace One is set to rendezvous with its target, extend a grappling arm to grab the picosatellite, and then plunge into Earth’s atmosphere, which would result in CleanSpace One’s destruction as well as the defunct satellite during reentry.

| The geopolitical environment that pervades the issue of space debris remediation will always be present, so it remains to be seen whether the nations of the world can subordinate geopolitical interests to address the growing space debris threat or whether one or two actors will take action in spite of it. |

This demonstration could sidestep the space weapon debate given that Switzerland has traditionally taken a neutral political stance in larger world affairs, and has no ongoing geopolitical issues with China or Russia. Therefore, the planned flight of CleanSpace One should not raise political objections, i.e. that the use of the technology to remove a satellite from orbit is disguised test of a space weapon capability. If no objections are raised, and CleanSpace One completes its mission as planned, it could lay the groundwork for a customary precedent of international space law.

However, Switzerland may not be able to create a recognized customary norm on its own. It may take a follow-on demonstration by one of the major space powers to solidify a customary rule of international law and extinguish the uproar over space weapons and space debris. It is at this point where the United States could follow in the footsteps of a successful Swiss effort and perform a space debris removal mission on a high profile space object that has been identified as space debris.

To pave the way, the United States would consult under Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty, detailing its plans to remove an identified space object that it has determined to be space debris. In support of this effort the United States would cite the successful Swiss effort as a precedent. Any objections raised during a consultation that the demonstration is a disguised space weapons test could be assuaged by pointing to the Swiss effort. The question is, after such a demonstration would countries like Russia and China decry the effort as a disguised space weapon test or remain silent and let customary international law etch a new norm into the legal consciousness of the jurisprudence of outer space? The answer to that question will not be known until it’s tried.

Conclusion

The ideas put forth in this series on space debris is not meant to be a comprehensive solution to the legal and political challenges to space debris remediation. Rather, this series of articles is designed to facilitate discussion on actual solutions to the legal and policy questions of space debris with the intent to solve them and make space debris remediation a reality.

The timing could not be more critical. A UN report released from the Inter-Agency Debris Coordination Committee during the 50th Session of the Technical Subcommittee of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space reports that space debris in LEO could reach a tipping point within the next century. Therefore, the time is now to find solutions to the legal and political challenges. The geopolitical environment that pervades the issue of space debris remediation will always be present, so it remains to be seen whether the nations of the world can subordinate geopolitical interests to address the growing space debris threat or whether one or two actors will take action in spite of it.