Crowdfunding spaceby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re seeing a lot of interesting things being done with crowdfunding,” said Hoyt Davidson of NearEarth LLC. |

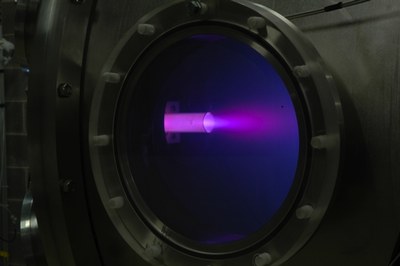

The goal of the test was to run the thruster for 60 seconds, but that milestone came and went and the thruster was still running smoothly. One of the company’s scientists, Andrew Case, continued to read out the elapsed time until, at 90 seconds, the head of Hyper-V, Doug Witherspoon, decided to end the test to avoid burning out any components. “Excellent!” he said to cheers and applause, as the thruster set a new firing duration record for the company.

While the thruster technology itself was innovative, what was also remarkable about the test was how it was funded. Hyper-V raised nearly $73,000 last fall through Kickstarter, a so-called “crowdfunding” web site that allows people to donate money to various projects, usually in exchange for products, gifts, or other forms of recognition. The March 28 test was designed to meet one of the goals of their Kickstarter campaign, to run the thruster for 60 seconds.

Hyper-V is not alone in turning to crowdfunding to support space-related projects. In the last year a number of companies and organizations have used Kickstarter and similar sites to raise modest amounts of money—only occasionally exceeding $100,000—needed for early stage development. It offers a way for companies to connect with larger groups of people who, individually, aren’t wealthy enough to back a project, but together can help a fledgling firm raise money, one of its biggest non-technical obstacles.

“On the small side, we’re seeing a lot of interesting things being done with crowdfunding,” said Hoyt Davidson, managing partner of NearEarth LLC, at the US Chamber of Commerce’s “Free Enterprise and the Final Frontier” event in Washington in February. “There’s a lot of interest among smaller investors to see things like this happen.”

One of the first successful space-related crowdfunding exercises was carried out a year ago by STAR Systems, a small venture in Phoenix that seeks to—eventually, at least—develop a suborbital spaceplane called Hermes (see “Hacking space”, The Space Review, April 23, 2012). STAR Systems raised just over $20,000 in its Kickstarter, allowing it to continue work on the hybrid motors that will power Hermes.

Mark Longanbach of STAR Systems said they took inspiration from a project on Kickstarter called KickSat, which raised nearly $75,000 in late 2011 to fund development of “chipsats,” or spacecraft the size of just a couple of postage stamps. “It was really my inspiration for realizing that the crowdfunding platform could be viable for actually getting some funding injected into your company,” he said during a presentation at the Space Access ’13 conference in Phoenix on April 12.

STAR Systems’s crowdfunding campaign and many other space-related efforts are quite different from more common uses of these platforms, which use crowdfunding to pay for product development and take pre-orders of new products. “They’re all based on the idea, the vision, they’re something the community can get behind because they can do something, they can make a difference,” Longanbach said. “You’re not just pre-selling an iPhone case or a charger or something like that, so it’s kind of a different mechanic versus a lot of other Kickstarter projects.”

| Raising a large sum of money through crowdfunding “comes with a really high level of scrutiny, and you can’t make everybody happy,” Laine said. |

One of the biggest successes in space-related crowdfunding has been LiftPort. Last summer, Michael Laine, seeking to revive the company that several years ago tried to develop technologies leading to a space elevator, set up a Kickstarter campaign to raise just $8,000 to fund a demonstration of robots climbing a two-kilometer tether suspended from a balloon. Then something remarkable happened: the campaign got picked up in social media as well as traditional media, and Laine ended up raising $110,353 by the time the campaign ended September 13.

“That took us from the hobby stage to, ‘Wow, I think we can do this for real,’” Laine said at Space Access. The Kickstarter funds will support experiments planned for May through July at increasing altitudes. Laine added a second Kickstarter campaign is in the works for August to help raise funds for a “String Sat” CubeSat to test tether technologies in orbit.

Others have used crowdfunding to support development of small satellites, technology development, and miscellaneous efforts. Rand Simberg used a Kickstarter campaign at first to support his research into spaceflight safety, raising more than $7,100. The result of that effort, he said at Space Access, was an “accidental book” called Safe Is Not an Option, which he raised more than $5,300 in a second Kickstarter to get published. The book is scheduled to be available in the coming weeks.

Crowdfunding has attracted a lot of interest in companies in aerospace and beyond because it’s seen as “free” money: unlike raising money from angel investors or other more traditional sources, crowdfunders don’t get an equity stake in the company, just access to a product, a gift, or even a feel-good sense of having supported a worthy cause. However, a lot of effort has to go into both the campaign itself as well as keeping the funders happy afterwards.

Laine said that of the $110,000 LiftPort’s Kickstarter raised, he ended up with about $99,000 after fees. The fulfillment costs for the various items people received for donating at various tiers ran about $45,000, he said. The unexpected surge in interest has also created delays in shipping out those items to donors. “It’s been eight months and I still don’t have all of my t-shirts out,” he said. His suggestion: “Have intangible rewards if you can.”

Laine’s effort attracted 3,468 backers, which creates complications of its own. Raising that much money “comes with a really high level of scrutiny, and you can’t make everybody happy,” he said. Most of those backers are happy, he said, but not all. In some cases, he said, people had the expectation that they were funding LiftPort’s long-term goal of a lunar space elevator, rather than an early-stage technology demonstration.

There’s also no guarantee of success. Golden Spike, the company that announced plans in December for commercial human lunar missions (see “Turning science fiction to science fact: Golden Spike makes plans for human lunar missions”, The Space Review, December 10, 2012), established a campaign on another crowdfunding site, Indiegogo, seeking to raise $240,000 to support outreach and design work. As of early Monday, with ten days left in the effort, Golden Spike has raised only about five percent of that goal.

Doug Griffith, a member of the board of Golden Spike, acknowledged the “very anemic” fundraising effort during a presentation at Space Access, but said the company was not giving up on using crowdfunding. He suggested that Golden Spike’s effort didn’t fit into two niches that work well in crowdfunding, particularly on Indiegogo: charitable efforts, and “supporting the underdog” competing against bigger companies and interests. “Golden Spike has been very challenging, and it’s not because people aren’t extremely excited about the idea,” he said, “but we don’t fit either of those two niches.”

Others are critical of crowdfunding because of the message it sends: that a company can’t attract more conventional investment. “This is fine for creative garage projects, but not for real companies,” said Ken Murphy, a space advocate who worked for more than two decades in the financial industry as an analyst, in an email interview. “It sends a bad message to real investors.”

| “The JOBS Act is a way to grow the space industry, if the government will let us,” Murphy said. |

One alternative has been in the works for a year now. The Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, signed into law a year ago, directed the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) would allow for crowdfunded investment: people not wealthy enough to be “accredited investors” under SEC regulations could instead invest smaller amounts of money for small stakes in a company: like the crowdfunding on Kickstarter, but receiving equity instead of a t-shirt.

The problem is that the SEC is months past the deadline in the act to promulgate the rules for crowdsourced investing. SEC officials said earlier this month that they plan to release those regulations “as soon as we can,” but declined to set a timetable.

Murphy is worried the rules could subvert the intent of the legislation, which was to allow more investors to participate in companies, supporting the economy in general. “The JOBS Act is a way to grow the space industry, if the government will let us,” he said.

So for now, companies continue to turn to portals like Kickstarter to win small amounts of funding. At Hyper-V, the success of last fall’s Kickstarter has led them to consider doing it again. “We’re thinking about it,” Witherspoon said. “We’re not sure if we’re going in that direction or not.” A more conventional alternative, he said, would be to apply for an SBIR award from a government agency.

“It’s not as easy as it looks,” Laine said of crowdfunding, “and it’s not as hard as it looks.”