To catch a planetoidby Jeff Foust

|

| “We decided to preferentially invest in the kinds of technologies we needed anyway,” a senior NASA official said of the technologies included in the asteroid initiative. |

What NASA unveiled on the 10th was a somewhat broader asteroid initiative, of which a mission to move an asteroid was the largest, but not only, aspect of it. NASA proposed $105 million for the initiative in 2014, spread over three of its mission directorates. Of that, $78 million would go to technologies needed for the proposed mission: $40 million to the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate for technologies to grapple “uncooperative” objects like spinning asteroids, and $38 million to the Space Technology Mission Directorate to work on a solar electric propulsion system that could be used by a robotic spacecraft that would move the asteroid.

The rest of the funding would go for applications that could support an asteroid retrieval mission but also help in planetary defense, a topic that has received renewed attention since the meteor explosion above the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February. NASA’s Science Mission Directorate would get an additional $20 million to support enhanced searches of near Earth objects, and Space Technology would get the remaining $7 million to study asteroid deflection strategies.

Spreading the funding across three mission directorates, rather than consolidating them under a single budget line item, was a deliberate decision by NASA, reflecting the uncertainty about the asteroid mission concept. “We decided to preferentially invest in the kinds of technologies we needed anyway,” a senior NASA official said prior to the budget’s release. All the technologies being funded in the proposal for an asteroid retrieval mission have other applications should the asteroid mission not go forward.

“This mission raises the bar for human exploration and discovery, helps us protect our home planet, and brings us closer to a human mission to an asteroid,” NASA administrator Charles Bolden said in a press conference about the budget April 10. “It brings together the best of NASA’s efforts in all areas to achieve the president’s goals faster and cheaper.”

| “This is kind of a proof-of-concept point solution,” Gerstenmaier told the NAC subcommittee. “This object [2009 BD] is not the object.” |

In a presentation last Thursday before the human exploration and operations subcommittee of the NASA Advisory Council (NAC), and again Monday before the National Academies’ Committee on Human Spaceflight, NASA associate administrator Bill Gerstenmaier said that the agency had looked at potential mission scenarios to redirect an asteroid into orbit around the Moon, with an emphasis on redirect. “You may have heard in the press that we’re going to actually drag the object back to the Moon,” he said Monday. “We don’t drag it, because it’s too massive. We essentially redirect it.”

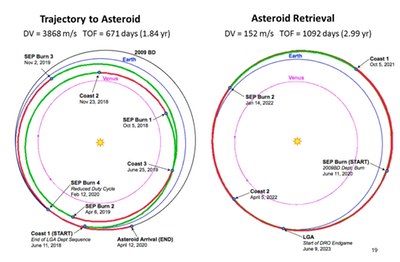

A slide from a NASA presentation showing a notional mission to the asteroid 2009 BD, redirecting it towards Earth. (Larger version) (credit: NASA)/div> |

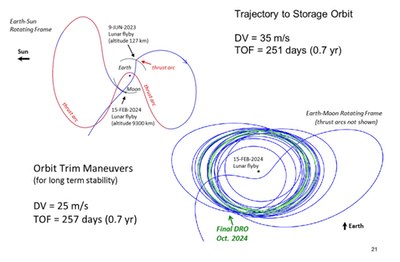

At both meetings, Gerstenmaier presented a mission scenario involving the redirection of one small near Earth asteroid, 2009 BD. In that mission, a robotic spacecraft with a solar electric propulsion system would leave Earth in June 2018, arriving at 2009 BD in April 2020. After grappling the asteroid (and, presumably, damping out its rotation to make it more controllable), the spacecraft would begin a series of maneuvers that bring it to the vicinity of the Moon three years later. Another series of maneuvers, lasting over a year, would put the asteroid into a “deeply retrograde” orbit around the Moon that would be stable for at least 100 years.

Once in this stable orbit, a crewed mission would fly to the asteroid on an Orion spacecraft launched by a Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket. That 22-day mission would include five days in the vicinity of the asteroid. The crew would perform two four-hour spacewalks during the day, Gerstenmaier said (since Orion does not have an airlock, the capsule would be depressurized for the EVAs.)

One immediate problem with the mission scenario is that it does not bring the asteroid to Earth in time to meet the goal announced in the budget proposal release of flying the mission in 2021, the current date for the first crewed SLS/Orion mission, designated EM-2 (EM-1 is the initial, uncrewed SLS/Orion mission in 2017.) “This is kind of a proof-of-concept point solution,” he told the NAC subcommittee. “This object [2009 BD] is not the object.”

A slide from a NASA presentation showing the maneuvers required to put asteroid 2009 BD into a lunar orbit. (Larger version) (credit: NASA)/div> |

Gerstenmaier’s comments raise one immediate issue with the asteroid mission as proposed: there is no known small near Earth asteroid that meets the size and orbit criteria to support a 2021 crewed mission. Gerstenmaier told the NAC that they know of about 300 near Earth asteroids with diameters of approximately 10 meters, of which 13 have suitable orbits. Astronomers are finding new qualifying asteroids at a rate of about one to two a year, he said.

That concern echoes a previous complaint about the administration’s original 2010 goal of a human asteroid mission by 2025: no one could identify a specific asteroid that such a mission could fly to by that deadline. In this case, the issue is compounded by the requirements that the object not only be in a suitable orbit, but be small enough to be redirected to lunar orbit.

However, discovering such small objects is difficult: they must come close to the Earth to be bright enough to be seen by groundbased telescopes, limiting what can be detected and thus what could be useful targets for such a mission. At last week’s Planetary Defense Conference 2013 in Flagstaff, Arizona, astronomers noted the difficultly in detecting something as small as the Chelyabinsk meteor, which, at approximately 17 meters in diameter, is considerably larger than the desired object for such a mission (see “Piecing together the Chelyabinsk event”, The Space Review, April 15, 2013).

“You can imagine how many people asked, after the recent Russian impact, why didn’t we find that,” said Tim Spahr, director of the Minor Planet Center, at the Flagstaff conference April 15. “We have good resources out there, but to find 20-meter objects is simply not going to be done with the facilities we have now. It requires something different.”

At the National Academies human spaceflight committee meeting, committee co-chair Jonathan Lunine, a planetary scientist, asked Gerstenmaier what NASA would do if it could not find a suitable near Earth asteroid to move into lunar orbit. Gerstenmaier suggested NASA might carry out other aspects of the mission, such as flying a solar electric propulsion spacecraft. “I would stick that spacecraft on a pretty demanding demonstration mission, which we planned to do anyway,” he said, “and I would place this spacecraft in that retrograde orbit and then use Orion to go to that retrograde orbit to prove that we can do all the activities we described and gain the experience we need.”

The idea of redirecting an asteroid into lunar orbit and sending a crew to it has raised some questions about both its feasibility and utility: can it be done, and if so, why? Some key members of Congress are struggling to find answers to those questions.

| “We’re looking forward to a partnership with NASA. There’s a lot the private sector can bring to this game,” Tumlinson said. |

“While getting points for creativity, a proposed NASA mission to ‘lasso’ an asteroid and drag it to the Moon’s orbit will require serious deliberation,” said Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), chairman of the House Science Committee, the day the budget proposal was released. “Seemingly out of the blue, this mission has never been evaluated or recommended by the scientific community and has not received the scrutiny that a normal program would undergo.”

In an April 17 hearing on the overall federal R&D budget proposal, Smith pressed John Holdren, director of the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, why such a mission was included in the budget, particularly given the lack of enthusiasm for a human asteroid mission identified in a recent National Research Council report on NASA’s strategic direction (see “What’s the purpose of a 21st century space agency?”, The Space Review, December 17, 2013).

“I think the situation has changed in a number of important respects since the National Research Council report which you quote,” Holdren responded. What’s changed, he said, is that NASA has developed “an extraordinarily ingenious and cost-effective new approach to that mission” by bringing an asteroid close to Earth. “Now we’re seeing a lot of enthusiasm for it.”

Smith did not seem convinced, though. “It is a new mission, maybe we need to wait and see how it is received by the scientific community,” he said. “It just seems to me to be a little bit of an afterthought.”

NASA’s interest in redirecting an asteroid comes after the announcement of two new companies in the last year, Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries, established to prospect and eventually extract resources from near Earth asteroids. Officials from both companies expressed hope that NASA would be willing to work with them on ways to involve the commercial sector in any asteroid capture mission.

“We’re looking forward to a partnership with NASA. There’s a lot the private sector can bring to this game,” Rick Tumlinson, chairman of the board of Deep Space Industries, said at the Space Access ’13 conference in Phoenix on April 11. “A correctly structured program to bring an asteroid into lunar orbit may be based on the COTS [Commercial Orbital Transportation Services] model, where we had a cooperative venture leading to a pay-for-services model. It might work very well in this case.”

“The US government’s investment in this area could be leveraged by commercial industry in a number of ways, from supporting the mission to identify, characterize, and, depending on the type of asteroid retrieved, develop ways to understand, extract, and utilize the resources from it once returned,” said Chris Lewicki, president and chief engineer of Planetary Resources, in a statement April 10.

Speaking at the Planetary Defense Conference in Flagstaff on April 15, NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver expressed an openness to working with such companies as part of NASA’s overall asteroid initiative. “When Planetary Resources was founded a few months ago, and following on that Deep Space Industries, I could not have been happier” because it demonstrated there was interest in asteroids beyond NASA, she said.

Garver said NASA would hold a workshop in the “June timeframe” to look how to best leverage the NASA investment and that the agency was open to tools like data buys and prizes to get information on identifying asteroids that could be potential targets of the proposed NASA mission. “We believe there are a lot of innovative ways, just like we are doing in other aspects of NASA” to support agency goals, she said.

| “I can’t assess it,” Squyres said of redirecting an asteroid. “I don’t know if this can be done or not. I don’t know what it’s going to cost.” |

Steve Squyres, a planetary scientist who is the current chair of the NAC, told the National Academies human spaceflight committee on Monday that NASA should be careful how it sells the asteroid mission concept to stakeholders and the general public. “It’s tempting to pitch it in terms of its contributions to asteroid exploration,” he said, noting he was speaking for himself and not on behalf of the NAC. However, he said such a redirection mission, with costs likely to be in the billions of dollars, would not be cost-effective in terms of studying asteroids versus robotic missions.

He also cautioned against selling a human mission to an asteroid in lunar orbit as satisfying the goal established three years ago this month to send humans to an asteroid by 2025. While NASA plans to send humans to an asteroid captured and placed in lunar orbit, Squyres pointed out the president’s April 15, 2010 speech specifically called for “the first-ever crewed missions beyond the Moon into deep space” by 2025, starting with a human mission to an asteroid.

Squyres said he believed that two of the three elements of the agency’s asteroid strategy, looking for near Earth asteroids and sending a human mission to a captured asteroid, made sense in that they were important outside of the context of the asteroid mission itself: the former had clear scientific utility, including looking for potentially hazardous objects, while the latter could be a stepping stone for more ambitious future human space exploration missions.

What was still unclear to him, though, was the actual redirection of an asteroid into lunar orbit. “I can’t assess it,” he said. “I don’t know if this can be done or not. I don’t know what it’s going to cost. It’s a very new idea, it’s very immature, it needs a really hard, carefully considered look, and then we’ll see.”

In other words, for now—and at least through a mission concept review planned by NASA for this summer—the idea of moving an asteroid into lunar orbit and sending humans to it still sounds to many like science fiction. Convincing Congress, other stakeholders, and the general public that NASA can turn that fiction into fact will be one of the agency’s biggest challenges this year.