The fault is not in the stars, but ourselvesby Dwayne Day

|

| It turns out that the show’s anti-missile system subplot has a strong basis in reality. |

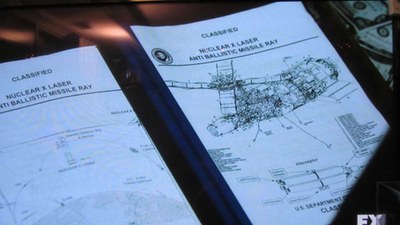

The third episode, titled “Gregory,” takes place in February 1981, and features a new subplot as KGB agent Phillip travels to Philadelphia for a clandestine meeting with an unknown source in a dank basement and trades a briefcase full of money for a folder full of documents. Upon opening the folder he sees two pages of schematics depicting aspects of an American anti-ballistic missile system. One of the schematics shows satellites in orbit with the label “X laser.” The other depicts a modified Skylab space station. The documents are awkwardly labeled “Nuclear X Laser Anti Ballistic Missile Ray.”

Subsequently, the Jennings record a conversation between senior American and British defense officials discussing the anti-ballistic missile system. A representative of Margaret Thatcher’s government informs the American official that Thatcher will support the shield provided that the Americans agree to extend it to Europe.

Of course, the filmmakers simply used the Skylab schematic as a prop, probably choosing the drawing because it was free of charge and somewhat recognizable. After all, they needed something that would look like a big satellite to an audience that probably does not remember Skylab at all. The seal for the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO), which did not form until a few years later, appears in the upper corner. Another document features a schematic that was actually produced in the late 1980s to depict the “Brilliant Pebbles” system of orbital interceptors.

The show is well-written and suspenseful, but has tended to juggle the actual history around a bit, and not only with fake documents. For instance, one character refers to the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1981, even though that project, popularly derided as “Star Wars,” was not actually announced by Reagan until 1983. That said, it turns out that the show’s anti-missile system subplot has a strong basis in reality.

In November 1980 the United States detonated a nuclear weapon underground in a test nicknamed “Dauphin.” The nuclear weapon was used to focus X-rays into a coherent beam for only a fraction of a second, but demonstrated that it was possible to create a beam that could potentially be used to burn ballistic missiles out of the sky—after the detonation of an orbiting nuclear weapon, of course.

Edward Teller, considered by many to be the father of the American hydrogen bomb, and his protégé Lowell Wood, soon began advocating this X-ray laser concept to the Reagan administration, which took office in January 1981. Somehow the fact of the successful test leaked to the trade publication Aviation Week and Space Technology soon thereafter, and appeared in the February 23 issue of the magazine, demonstrating why it had earned the moniker “Aviation Leak.” Probably by no coincidence, February 23, 1981 is almost exactly the time period of the episode of The Americans featuring the anti-ballistic missile subplot.

| The United States never considered using orbiting systems anywhere as big as Skylab. Ironically, the Soviets did. |

Years later it was revealed that the results of the Dauphin X-ray laser test had been exaggerated by its advocates and many people concluded that the concept was unworkable. Soon after Reagan formally announced the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1983 it became a major point of contention during the Cold War, both between the US and Soviet governments and in the anti-nuclear communities. The history of SDI has been chronicled in numerous places, usually not sympathetically. It was scaled back when the Cold War ended, and dramatically redirected towards ground-based interceptors by President Bill Clinton in 1993, by which time SDIO was also renamed the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization.

The United States never considered using orbiting systems anywhere as big as Skylab. Ironically, the Soviets did. In fact, the Soviet Union had a space-based anti-ballistic missile program that preceded the American one and was in many ways more extensive. By the 1980s it had evolved to include many systems for attacking American spacecraft, such as a series of very large chemical laser satellites named Polyus-Skif that would have been launched on the large Energia rocket. Ultimately, the Soviet Union collapsed under its own unworkable economic and political systems and the Soviet Star Wars program never progressed to significant flight testing.

The Americans frequently embraces the ironies of the Cold War, where both sides were constantly misinterpreting the actions of their rivals with dangerous consequences. The excellent episode on the Reagan assassination attempt, for instance, focused on how badly the Soviet intelligence services understood the reaction of the American government to the crisis, translating some clumsy comments by a former general as an indication that a military coup was underway. In the season finale, Phillip meets up with an Air Force colonel who has provided them with some shocking information on how advanced the American ballistic missile defense technology is. But then he gets a big surprise: “It will take fifty years or more to make this work,” the colonel tells him, and the reason he is sharing the information with the Russians is to try and avoid a costly arms race in space. The Americans has been renewed for a second season, but we all know how unsuccessful the colonel was. We all know how that story ends.